6 Final Thoughts on 2022 USAs: Could the US Men Sweep the Sprints at Worlds, Pacemakers, Sha’Carri & More

By Jonathan Gault

June 29, 2022

The 2022 USATF Outdoor Championships are over, and after Thursday’s Stockholm Diamond League, most everyone in the sport will have two weeks to relax before the World Championships kick off at Hayward Field on July 15. That break is much-needed after a very busy spring of track & field.

I already shared many of my thoughts on USAs in our written recaps and on the LetsRun.com Track Talk Podcast, but I’m not quite done. After a few days of perspective following the weekend in Eugene, here are my final takeaways from a dramatic 2022 USA meet.

Moments of the weekend

In no particular order, the moments that had me buzzing last weekend:

- Fred Kerley‘s remarkable weekend. In the span of 26 hours on Thursday and Friday, Kerley ran the three fastest 100m races of his life and three of the four fastest 100m races of 2022 (9.83 in the prelims, 9.76 in the semis, 9.77 in the final). And then he ran three more races on Saturday and Sunday to make the team in the 200.

- Ryan Crouser‘s monster series. Only three humans have thrown 22.98m or farther in the shot put. One is Randy Barnes (convicted doper) and one is Ulf Timmermann (an East German in the 1980s…you connect the dots). The other is Crouser, who did it on each of his final four throws at USAs: 23.12, 23.01, 23.11, 22.98. It’s the first time any human has thrown 22.98 or better twice in a series, and Crouser did it four times.

- Melissa Jefferson‘s breakthrough. The diminutive Jefferson (she’s been measured at 5-foot-3 but likes to tell people she’s 5-foot-4) was only 8th at NCAAs for Coastal Carolina but stormed to a 10.82 pb in the 100m semis before blasting a 10.69 (+2.9) to win the final. Mixing it up for a medal against the Jamaicans at Worlds will be a tall order, but at just 21 years old, Jefferson has a bright future.

- Cooper Teare gets it done in a tactical race. Even Teare himself admitted he was hoping for a fast race in the men’s 1500 final. It didn’t happen, but in an event where the other favorites fell by the wayside, Teare was left standing as the US champion in 3:45.86 thanks to a 51.90 last lap.

- Evan Jager making the team in the men’s steeple. There are two marks of a truly great athlete. One is what they can accomplish at their absolute best — we saw that with Jager in the 2010s, running an American record of 8:00 and taking silver at the Olympics. The other is what they can summon when they’re not at their best. Jager spent much of the last four years in injury hell and entered USAs off the back of three unimpressive races and a season’s best of 8:27, five seconds off the Worlds standard. But he came up clutch to run 8:17 in the final, finishing second and clinching a berth on his seventh US team (don’t forget that 5k team in 2009!). His emotional release coming off the final hurdle was spine-tingling.

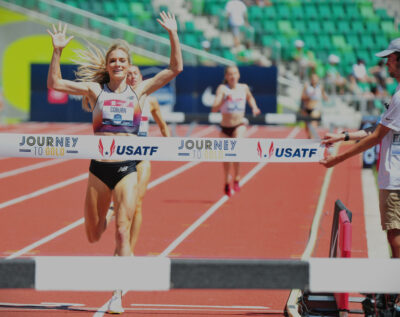

- Sydney McLaughlin‘s world record. The (impossibly high) expectation foisted upon McLaughlin when she turned pro in 2018 is that she would become the greatest women’s 400-meter hurdler in history. Now, at the age of 22, she may be close to locking up that honor. McLaughlin has run a world record in each of her last three championship finals, including 51.41 in Eugene on Saturday, and could well go faster at Worlds next month. What a talent.

- Rai Benjamin running a world-leading 47.04 to win the 400 hurdles. He revealed after the race he hadn’t run over a single hurdle between the Doha Diamond League on May 13 and USAs due to COVID and a hamstring injury.

- Athing Mu vs. Ajee’ Wilson in the women’s 800. Athing Mu still hasn’t lost an 800-meter race as a pro, but Wilson, the World Indoor champion, came closer to beating her than anyone before, edging ahead with just 30 meters to go before Mu passed her back at the line to win in 1:57.16 to Wilson’s 1:57.23. Mu will go into Worlds as the favorite but Wilson served notice that she is not invincible.

- Noah Lyles vs. Erriyon Knighton in the men’s 200. The race itself was incredible, Lyles storming back from a couple meters down off the curve to pip Knighton at the line, 19.67 to 19.69. And Lyles’ celebration — pointing across Knighton’s body at the finish line — added some fuel to a budding rivalry and should make their clash at Worlds next month even more interesting.

Could the US men sweep every sprint gold at Worlds?

Year-in, year-out, there is no tougher national team to make than the United States. On a recent appearance on the Citius Mag Podcast, sprint star Joseph Fahnbulleh, who finished 5th in the Olympic 200m last year, was asked why he chose to represent Liberia instead of the United States, where he was born and raised. Fahnbulleh said one reason was to honor his mother, who was forced to leave Liberia at age 12. But his other reason was revealing.

“What people don’t understand is if you don’t have trials, you’re kind of solid,” Fahnbulleh said. “USA trials? Bruh, you have to peak and then peak again [for Worlds]. That’s crazy…Not having a trials for Liberia sets me up for a longer career in life. I don’t have to peak, I don’t have to worry about if I’m going to make the team and is my contract going to get reduced if I don’t make the team.”

It’s true. Even Olympic medalists have to be close to their best for the US trials or risk missing the team. Check out the times that won gold and bronze at last year’s Olympics and the times of this year’s US champion and 3rd placer in the men’s sprints:

| Event | 2021 Olympics 1st | 2022 USAs 1st | 2021 Olympics 3rd | 2022 USAs 3rd |

| 100 | 9.80 | 9.77 | 9.89 | 9.88 |

| 200 | 19.62 | 19.67 | 19.74 | 19.83 |

| 400 | 43.85 | 43.56 | 44.19 | 44.17 |

| 110H | 13.04 | 13.03 | 13.10 | 13.09 |

| 400H | 45.94 | 47.04 | 46.72 | 47.65 |

So in three of the five men’s sprints, the winning time at this year’s US champs was faster than the winning time at last year’s Olympics and the third placer at USAs ran faster than the Olympic bronze medalist.

As of today — 16 days out from the start of Worlds — Americans hold the world-leading time in all five men’s sprint events, three of which were set at USAs last week (Fred Kerley 9.76 in the 100, Michael Norman 43.56 in the 400, Rai Benjamin 47.04 in the 400H). Could the US win all seven men’s sprint events at Worlds (100, 200, 400, 110H, 400H, 4×100, 4×400)? Seems possible, right?

Hold on a second. This sounds familiar. After all, at this time last year, the US men also had the world leader in all five sprint events and wound up winning only one gold on the track (in the men’s 4×400, which the US should never lose). Here are the winners from last year’s Olympic Trials and what happened to them in Tokyo:

100: Trayvon Bromell (9.80) — Cratered at the Olympics and didn’t even make the final.

200: Noah Lyles (19.74 WL) — Ran the same time in Tokyo as he did at the Trials but that was only good enough for bronze.

400: Michael Norman (44.07) — 5th at the Olympics in 44.31.

110H: Grant Holloway (12.96; ran 12.81 WL in semis) — Silver in 13.09 after getting run down by Hansle Parchment.

400H: Rai Benjamin (46.83 WL) — Ran incredibly at the Olympics (46.17) but beaten by one of the greatest performances in track & field history by Karsten Warholm (45.94).

What are the takeaways? Three big ones:

1. The track at Hayward Field is one of the fastest in the world. The same performance on a different track could be a few hundredths slower.

2. Fahnbulleh is right. Running one world-class performance (which is what it takes to win the US trials) and following it up with another a few weeks later is extraordinarily tough.

3. The US men underperformed at the Olympics.

That said, the US men are well-positioned to win a ton of medals in Eugene next month, and a couple of big injuries to rival sprinters mean a sweep, though unlikely, is very much a possibility. Running through each event quickly:

100: Reigning Olympic champ Marcell Jacobs of Italy has missed most of the spring with a thigh injury, meaning an American, led by Fred Kerley, will be favored for gold.

200: Olympic champ Andre De Grasse of Canada always peaks well but he’s been poor this year while Noah Lyles and Erriyon Knighton have been sensational. Anything other than a Lyles/Knighton victory would be a massive upset.

400: Tough choice. Do you go with Michael Norman, who has the two fastest times in the world this year but hasn’t fared well in his two appearances at global championships, or the Bahamas’ Steven Gardiner, who has only run 44.21 this year but has won the last two global titles and hasn’t lost a 400 since 2017?

110H: Between Grant Holloway, Daniel Roberts, Trey Cunningham, and Devon Allen, this is one of the strongest teams any country has ever sent to a World Championship in any event (Roberts and Holloway are tied for #3 in the world this year at 13.03 and they have the slowest SBs on the US team). Sending four studs gives the US a great chance at gold but Olympic champ Hansle Parchment, who hasn’t lost in 2022, lurks.

400H: Rai Benjamin has had a rough spring battling a bad case of COVID and hamstring tendinitis, but he looked great at USAs with a world-leading 47.04 and world record holder Karsten Warholm’s health is a major question mark after injuring his hamstring in Rabat on June 5. Benjamin still has to deal with Alison dos Santos, who beat him earlier this year in Doha.

4×100: On paper, the US should win this every year but something inevitably goes wrong.

4×400: The one event where the US is a lock for gold.

Could the US men get shut out of the medals in the distance events?

An American man has medalled in a distance event (800, 1500, 5k, 10k, steeple, marathon) at eight of the last nine global outdoor championships, with the US taking home an average of 1.89 medals per champs during that span.

American men’s distance medalists, last nine global champs

| Year | Medals | Medalists |

| 2009 Berlin | 2 | Bernard Lagat (1500/5K) |

| 2011 Daegu | 2 | Matthew Centrowitz (1500), Bernard Lagat (5K) |

| 2012 London | 2 | Leo Manzano (1500), Galen Rupp (10K) |

| 2013 Moscow | 2 | Nick Symmonds (800), Matthew Centrowitz (1500) |

| 2015 Beijing | 0 | None |

| 2016 Rio | 5 |

Clayton Murphy (800), Matthew Centrowitz (1500), Evan Jager (SC), Paul Chelimo (5K), Galen Rupp (marathon)

|

| 2017 London | 2 | Evan Jager (SC), Paul Chelimo (5K) |

| 2019 Doha | 1 | Donavan Brazier (800) |

| 2021 Tokyo | 1 | Paul Chelimo (5K) |

The 2022 situation isn’t totally dire. Medals in the steeple and marathon are unlikely (normally a hot-weather marathon on home soil would be a great situation for Galen Rupp, but the 36-year-old was awful in his two road races earlier this year), but Bryce Hoppel medalled at World Indoors this year in the 800 and was 4th at the last World Championships. He’s definitely got a shot in an event with no obvious favorite. Cooper Teare has an outside shot at a medal in the 1500 but at best has the sixth-best odds behind Jakob Ingebrigtsen, Abel Kipsang, Ollie Hoare, Timothy Cheruiyot, and Jake Wightman.

Ironically, the US’s best shot at a men’s distance medal may come in an event in which an American has never medalled at Worlds: the men’s 10,000. Grant Fisher was 5th in the Olympics last year, and he’s running a lot better in 2022 than he was in 2021. Plus two of the men who beat him in Tokyo may not be in the 10k in Eugene: bronze medalist Jacob Kiplimo hasn’t raced on the track all year and 4th-placer Berihu Aregawi was only named to the Ethiopian team in the 5,000.

There’s enough talent on Team USA to eke out one medal, but if I were an oddsmaker, I’d set the over/under for US men’s distance medals at 0.5, not 1.5.

Repeating is hard to do (except if you’re Emma Coburn & Keni Harrison)

If you were a US track champion at the 2021 Olympic Trials, you were just as likely to repeat in 2022 (Noah Lyles, Michael Norman, Hillary Bor, Rai Benjamin, Athing Mu, Emma Coburn, Elise Cranny, Keni Harrison) as you were to miss the 2022 team entirely in that event (Clayton Murphy, Cole Hocker, Paul Chelimo, Woody Kincaid, Javianne Oliver, Gabby Thomas, Quanera Hayes, Emily Sisson). A reminder of just how hard it is to win consistently at the US championships.

So we should truly appreciate what Keni Harrison and Emma Coburn have done in recent years. Harrison won her fifth straight US title in the 100 hurdles over the weekend, running a world-leading 12.34 into a 1.5 m/s headwind. Coburn won her eighth straight title in the steeplechase and moved to 10-0 in her career at USAs (she also won titles in 2011 and 2012 but missed 2013 due to injury).

The quality of their events makes Harrison and Coburn’s dominance even more impressive. The US is annually the strongest nation in the world in the women’s 100 hurdles, while Coburn has had to deal with Courtney Frerichs, the American record holder and a two-time global silver medalist. Remember when Harrison, who failed to make the Olympic team in 2016 but set the world record two weeks later, had a reputation for choking at major championships? That seems a long time ago. That being said, she’s run slower in the final of each of the last three global outdoor championships than she did in the US final and an outdoor gold would go a long way toward cementing her legacy.

Below, a list of the US champs in 2021 and 2022.

Men

| Event | 2021 champion | 2022 champion | Note |

| 100 | Trayvon Bromell | Fred Kerley | |

| 200 | Noah Lyles | Noah Lyles | |

| 400 | Michael Norman | Michael Norman | |

| 800 | Clayton Murphy | Bryce Hoppel | |

| 1500 | Cole Hocker | Cooper Teare | |

| 3K SC | Hillary Bor | Hillary Bor | 3 straight |

| 5K | Paul Chelimo | Grant Fisher | |

| 10K | Woody Kincaid | Joe Klecker | |

| 110H | Grant Holloway | Daniel Roberts | Holloway didn’t run ’22 final |

| 400H | Rai Benjamin | Rai Benjamin | 3 straight |

Women

| Event | 2021 champion | 2022 champion | Note |

| 100 | Javianne Oliver | Melissa Jefferson | |

| 200 | Gabby Thomas | Abby Steiner | |

| 400 | Quanera Hayes | Talitha Diggs | |

| 800 | Athing Mu | Athing Mu | |

| 1500 | Elle St. Pierre | Sinclaire Johnson | |

| 3K SC | Emma Coburn | Emma Coburn | 8 straight |

| 5K | Elise Cranny | Elise Cranny | |

| 10K | Emily Sisson | Karissa Schweizer | Sisson didn’t run ’22 final |

| 100H | Keni Harrison | Keni Harrison | 5 straight |

| 400H | Sydney McLaughlin | Sydney McLaughlin |

Pacemakers in championship finals are kind of lame

I believe pacemakers have a place in the sport of track & field. Watching athletes run fast can be fun, and pacemakers can help achieve that. But I don’t believe they should have a place in championship finals. The whole appeal of a championship final is it’s about head-to-head racing. Find a way to get to the finish line first. That’s it. At the pro level, if your only role in a championship final is to help out someone else, you shouldn’t be in the race.

That said, I’m not going to throw a tantrum about this. There are way bigger issues in our sport that need fixing. What Hillary Bor and Evan Jager did in Sunday’s 5,000-meter final is totally legal and I understand why they did it; heck, I did the same thing myself at the 2013 Heps for Dartmouth, helping to push the pace in the 5,000 because my coach thought my teammates would benefit from a faster race (it didn’t work; we scored a grand total of one point). Hillary knew his brother Emmanuel had a better chance of making the team if the pace was fast; ditto Jager for his training partners on the Bowerman Track Club. What both men did was selfless; I’m not going to rip them for being good teammates.

But it doesn’t mean I have to like it. Championship finals are meant to be even playing fields; anyone in there solely to help a teammate is tilting that field.

I was also curious why Jager chose to help push the pace. Yes, BTC’s Grant Fisher does better in faster races…but wouldn’t BTC’s Woody Kincaid, the best kicker in the field, want it to be as slow as possible? Not necessarily, as Jager explained in a text to LetsRun.

“I don’t know the specifics of what [BTC coach] Jerry [Schumacher] told all the guys,” Jager wrote. “I believe he met with them individually. But I’m pretty sure everyone wanted and agreed on how things played out. Also, if it’s a slow race, you leave more guys in it and a fast last lap becomes more of a crap shoot. I’m sure Woody thought he was just as strong if not stronger than everyone else in the race. And I think Woody has shown he has the best kick regardless of pace lol.”

On Sha’Carri Richardson and Cole Hocker

There were two enormous stories on day 1 of the 2022 USATF Outdoor Championships: Sha’Carri Richardson failing to advance out of round 1 in the women’s 100 meters and Cole Hocker failing to qualify for the final in the men’s 1500 meters. Neither spoke to the media after the race.

After declining to talk after both of her races in the 200, Richardson returned to the mixed zone at the end of the meet and made the following statement:

I’m coming to speak, not on just my behalf but all athletes’ behalf, that when you guys do interviews, y’all should respect athletes more. Y’all should understand them coming from whether they’re winning, whether they’re losing, whatever the case may be. Athletes deserve way more respect than when y’all just come and throw cameras into their faces.

Understand how an athlete operates and then ask your questions. Then be more understanding of the fact that they are still human, no matter just to the fact that y’all are just trying to get something to put out in an article to make a dollar. Thank you.

Richardson did not take questions from the assembled press pack but did stop for an interview with Citius Mag’s Katelyn Hutchison, saying “I always have time to talk to my Black queens.”

A few thoughts:

- I strongly believe it’s better for the sport when athletes stop to talk to the media after their races — and the vast majority do stop. That said, I’m not sure if USATF should require athletes to stop, as some suggested after Hocker and Richardson didn’t talk last week. The NBA and NFL fine their athletes for not talking to the media, but the NBA and NFL also pay those athletes millions of dollars per year. USATF pays its athletes very little.

- Unless you qualify for a team, here’s how it works for athletes at USAs: you finish your race, step off the track, walk through the mixed zone, then walk into an athlete recovery tent to collect your belongings. Then you’re allowed to leave. For an athlete like Hocker or Richardson, you might have one or two minutes to process what has happened before being descended upon by a horde of media wanting to know why you failed. That’s a very tough, emotional spot to be in for a young athlete (Hocker is 21, Richardson 22) and I can understand why speaking to the press might not appeal to someone whose dream has just been crushed.

- One possible solution: give athletes the option to go through the recovery tent before the mixed zone. They’d still be required to walk through, but it would give athletes who have have suffered a devastating defeat the chance to calm down a little and collect themselves.

- What Richardson asked for in her comments above is a fair request. All athletes deserve respect and empathy from the press. But to echo the comments of KVAL’s Hayden Herrera, I didn’t see any cases of media treating athletes disrespectfully in Eugene. Richardson’s comments stemmed from seeing Gabby Thomas crying in her interview after missing the team in the 200. But Thomas wasn’t crying because the media mistreated her; she was crying because, despite her best efforts to recover from a grade 2 hamstring tear, she could not produce her usual level of performance in the 200-meter final.

- Last weekend was my eighth USATF Outdoor Championship and it featured easily the most diverse mixed zone of the lot. Black voices — especially female black voices — have been almost non-existent in that space in previous years, so this was a welcome change. I totally understand why an athlete like Richardson might be more comfortable talking to someone like Katelyn Hutchison instead of me. But it’s dangerous when athletes start picking and choosing which members of the media they talk to in a mixed zone. Hutchison’s interview with Richardson focused on her on-track style; she did not ask at all about her races, meaning sprint fans went the entire weekend without hearing Richardson discuss one of the biggest storylines of the meet, her stunning underperformance in the 100 meters. Richardson wants respect and empathy, but it’s a two-way street. We want to understand athletes. We want their voices in the stories we tell about them. If you, as an athlete, want a better relationship with the media, that starts with opening up a little and taking questions. Because it’s hard to mend a relationship when only one side is talking.