10 Years Later: Finding Kenny Cormier

Ten years ago today, Kenny Cormier was the Foot Locker champion; a year later, he was an All-American at Arkansas as a frosh; two years after that, he walked away from the sport to enlist in the Marine Corps. Where is he now? That’s a bit complicated.

By Jonathan Gault

December 11, 2014

Kenny Cormier is a hard man to find. I suppose that’s only appropriate for someone that served five years in the Marine Corps as a sniper, but it’s decidedly inconvenient if he’s the subject of a profile assigned by your editor. Occasionally, his name will pop up in running circles, “Whatever happened to Kenny Cormier?” but that conversation, in person or online, rarely lasts more than a few minutes. “Joined the military,” someone will offer, before talk turns to the next prodigy that never made it.

Eventually, I get an email address and set up a Skype interview, but even after speaking to the man, I can’t tell you where he is right now. Cormier is a private military contractor and can’t say anything about his current whereabouts. Based on the time of our conversation, I’d guess Europe, but even that could be wrong.

Cormier, 29, remains fit, though he does not sport the trademark sunglasses that he wore during a cross country career that included a win at the 2004 Foot Locker finals. A full beard sits below his blond head of hair. The walls behind him are white, sparse and undecorated, save for the rifle hanging on the wall.

A few days ago, a friend sent him an email reminding him that this December will mark 10 years since his Foot Locker victory. It seems an eternity ago to Cormier. Some of the names in the results that year are immediately recognizable in the running community — Andrew Bumbalough (boys’ 2nd place) and Jenny Barringer (now Simpson, girls’ 10th place) are top U.S. pros right now — but there are far more names, like Cormier’s, that have faded from the public’s memory as the years wear on (Aislinn Ryan was the girls’ champ that year). Every name in those results has a story attached to it, but most of them aren’t as familiar to fans as Bumbalough’s or Simpson’s. This is Kenny Cormier’s story.

A Soccer Player/300-Meter Hurdler Finds His Passion

Cormier started out his track and field career as a 300-meter hurdler in Douglas, Ariz., a town of 17,000 on the Mexican border. Though he ran for the Douglas High School team, he was homeschooled by his mother, Jenny, just like his eight brothers and sisters. Cormier was hooked on the hurdles, but after going out for cross country as a sophomore, he realized his talents lay with the longer distances. He played other sports too — baseball and soccer, the latter under his father, Ken — but it didn’t take long for running to consume Kenny. He began scouring the Internet for training logs and read about the philosophies of top coaches, incorporating their advice into his training. Kenny finished 10th in the Arizona state meet as a sophomore and third as a junior despite running with a severe cold. Still, like many young runners, he experienced a rude awakening at the next level of competition. He went to the 2003 Foot Locker West Regional in Walnut, Calif., and finished 79th.

“That’s when I really realized how big the sport was and how much I needed to train to be as good as I wanted to be,” Kenny said.

So with that, he amped up his training, increasing his mileage from 70-80 miles per week to around 100 as a senior, with a high of 120. He ran at least 90 miles every week his senior fall until the final two weeks of the season, when he tapered for Foot Locker regionals and finals. Kenny would pass up nights of movies and pizza with his friends to rest up for the next day’s workout or race. He also gave up soccer, a difficult decision but one that his coach could sense was coming.

Aislinn Ryan and Kenny Cormier celebrating their 2004 Foot Locker wins.

Aislinn Ryan and Kenny Cormier celebrating their 2004 Foot Locker wins. Photo by trackandfieldphoto.com.

“His junior year, I could tell he lost some interest in playing [soccer] and [he] said that he would play but that it couldn’t interfere with his running,” Ken said.

The Cormiers would have disagreements — as his soccer coach, Ken didn’t want Kenny to run on game days, but the younger Cormier was inflexible when it came to compromising his training. Eventually, Kenny told his dad that he wasn’t going out for the soccer team that year.

“I only have one question for you,” Ken responded. “Where are you planning on living?”

That was a joke, but there was no joking about Kenny’s passion for the sport.

Kenny’s passion was rewarded as he improved dramatically during his final year of high school. He started his senior year with modest pbs of 4:21, 9:23 and 16:15, but he won the Arizona state meet, the Foot Locker West Regional and then the Foot Locker Champs where he took down a field that included Bumbalough, an 8:51 guy, 8:54 guy and 4:06 miler.

In track, Kenny added another national title in the indoor two-mile and committed to run at the University of Arkansas under the legendary John McDonnell. Ken, in true coach fashion, had always told his son that if he wanted to be the best, he had to beat the best, and beating the best required training with the best. Prior to Kenny’s commitment, Arkansas had won 11 of the last 21 NCAA championships in cross country. As a result, Fayetteville was where he wanted to be.

A Fast Start In Fayetteville – “I thought he was going to be one of our greats”

If you took a poll of Cormier’s Arkansas teammates after his freshman year, the majority would have said that they were training with a future NCAA champion. Cormier was that good. In his first season in Fayetteville, Cormier finished fourth at the SEC Championships and 28th at the NCAA XC Championships. He was An All-American, the top American true freshman and the third man on Arkansas’ runner-up team.

“I thought he was going to be one of our greats,” McDonnell said. “He had it all — the head, the body.”

Fellow high school star Chris Barnicle met Cormier for the first time at Foot Lockers in 2004 (Barnicle finished sixth) and the two hit it off. They exchanged contact information with each other and a couple of guys from the South region, Dan LaCava and Scott McPherson, and started talking to each other through AIM, the Internet instant messaging service every teenager was addicted to 10 years ago. They spoke about how cool it would be if they all ended up at school together, and that’s exactly what happened: the four shared a dorm their freshman year in the Northwest Quad. All four entered as prized recruits — they were Foot Locker finalists, after all — but Cormier separated himself early on.

McDonnell kept Cormier’s mileage similar to what he had run in high school but ramped up the intensity. McDonnell’s Razorbacks teams were famous for hammering easy runs, and it wasn’t uncommon to see the team dip below 5:45 pace on a run. What was uncommon was to see a freshman leading the pack.

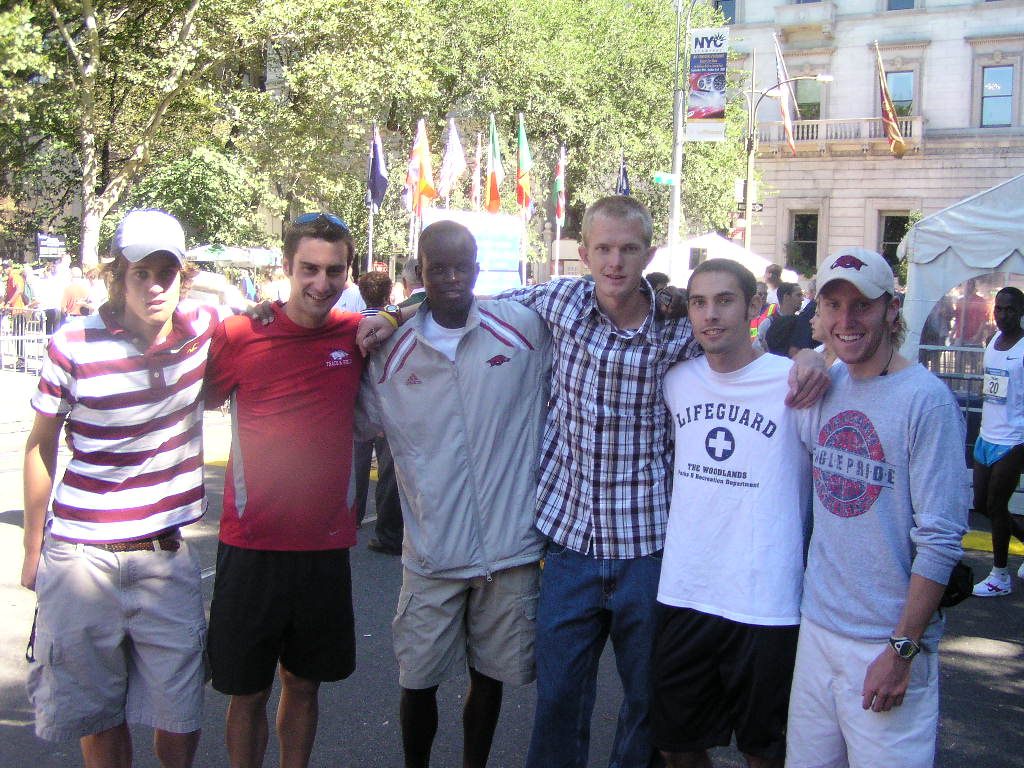

Cormier (#64) on his way to All-American honors at the 2005 NCAA champs.

Cormier (#64) on his way to All-American honors at the 2005 NCAA champs. Photo by trackandfieldphoto.com.

“We used to do this figure-eight loop and I’d see Kenny pushing the pace ahead of Alistair [Cragg, the seven-time NCAA champ, who was still training in Fayetteville and would eventually run 13:03], Josphat Boit (2006 NCAA indoor 5,000 and outdoor 10,000 champ, eventual pbs of 13:17/27:40), Shawn Forrest (2009 NCAA 10,000 runner-up to Galen Rupp),” Barnicle said. “Kenny’s this 19-year-old kid putting them in the hurtbox.”

Expectations were high heading into Cormier’s sophomore year. In practice at the start of the season, Cormier ran the Bridge Run — a 14.5-mile loop that was one of the program’s most fabled runs — in 1:14 (5:06 pace), breaking Cragg’s course record.

Micky Cobrin, who transferred to Arkansas from UCLA before Cormier’s sophomore year in 2006, recalled how hard it was to stay with Cormier in practice:

“I was coming off a hernia surgery, just getting back into shape. I would do four miles when the team would do 10, so I would just run with the front guys the whole way because I was only doing four. I ran with Kenny, who was the person in front at that time, and he was on his way to a 10-mile run. I had done four of the miles with him and I was just dead. It was the hardest I had ever run that far and he was going twice that far and more….I was thinking, this guy’s going to be a national champ…I remember I gave our coach this look when I was coming off the trail like, ‘This guy’s crazy.'”

But once the racing started, it was soon clear something wasn’t right. Cormier, who was expected to be one of the nation’s very best, was struggling to keep his place in the top seven. Barnicle felt off as well. They went to the team’s nurse practitioner several times, beginning in mid-September, but she couldn’t figure out what was wrong with them. Initially they had low white blood cell counts and the nurse practitioner thought they were anemic, but Barnicle knew that wasn’t it.

Eventually, after racing the entire season and even being tested for HIV and cancer, Barnicle went to the hospital and used his own health insurance to get tested for mononucleosis. It came back positive. Cormier got tested shortly thereafter. He, too, had mono, and yet he had somehow been able to finish the season as Arkansas’ fourth man, taking 74th at NCAAs.

“That’s just Kenny being Kenny, one of the toughest guys out there,” Barnicle said.

Barnicle still harbors resentment for their misdiagnosis, but Cormier is willing to let bygones be bygones (a message left for the nurse practitioner at her office regarding this story was not returned).

“A couple years ago, I’d probably be pretty bitter about it; now it’s something I look at and laugh,” Cormier said. “People make mistakes. It’s interesting how something like that can send you on a new course.”

Cormier attacked his rehabilitation with the same fervor he brought to races. He and Barnicle were told to take three to five weeks off; while Barnicle enjoyed not having to run every day, Cormier lasted about a week without training before taking matters into his own hands.

Since Cormier still wasn’t supposed to be running, he had to get creative to fit in his training. The team ran every morning at 7:00 a.m., so Cormier got up at 5:00 to get in his morning run unnoticed. Then, while the team was eating dinner at 6:00 or 7:00 p.m., Kenny would head out the door for his second run of the day. During a time when he wasn’t supposed to be running, he ended up running more than he did in the fall — up to 120 miles per week — before his mono relapsed. The doctors made it clear this time: come back too early and he’d risk getting chronic fatigue syndrome.

“There were people babysitting him, making sure he wouldn’t get out the door,” Barnicle said. “Just the way Kenny is, hard work is what has brought him everywhere. That was driving him crazy.”

“There’s a lot more to life than just running….Walking away from a sport isn’t admitting failure. It’s not.”

Cormier ended up taking six months off, and when he came back during the summer of 2007, his found that his heart wasn’t in it anymore. He had come into conflict with McDonnell about his rehab and eventually communication between the two broke down. More importantly, the insatiable desire for greatness that had driven Cormier before his diagnosis was missing. Now that his identity was no longer tied up in times and places, he got a clear view of Kenny Cormier, the person. He decided it was time to end his running career.

“I compare it to a fog lifting,” Cormier said. “I realized I probably wasn’t going to be too excited to look back in 10 years and see I dedicated my entire young adult life to a sport…The only reason I kept my grades up was to continue to run…It’s really difficult for a lot of guys just because of the culture we live in, the sports culture of when you walk away from a sport it’s kind of like you’re failing. There’s a lot more to life than just running. Some guys are going to have a professional career, but walking away from a sport isn’t admitting failure. It’s not. It’s enjoying it for a period of your life and moving on from there.”

Cormier was ready for a new challenge. Without running to anchor him during the fall of 2007, Cormier had begun to skip class and mostly sat at home playing Assassin’s Creed. After the first semester, Cormier packed up his belongings and drove the 1,100 miles back to Douglas with no intention of returning. As soon as he got back, he completed the recruitment process for the Marines. He had always wanted to travel the world and the military held a special appeal to him, though he hadn’t spoken much about it to his friends or family. Cormier considered transferring to Arizona State (coach Louie Quintana had shown interest), but he knew fairly quickly upon leaving Arkansas that if he was ever going to join the military, this was the time.

It all came as a surprise to his parents, who were under the impression that Kenny was taking time to weigh his options, before transferring to another school.

“To say that his mom and I were shocked when he said he was joining the Marines was a major understatement,” the elder Cormier said.

Ken realized that his eldest son was a man now, capable of making his own decision.

“He wasn’t discussing with us whether it was the right thing to do, but just informing us that that was the right time for him to do that,” Ken said. “He listened to all our arguments. We did our best to try and convince him that maybe there were other alternatives, but he already knew [what he wanted to do.]”

Kenny hadn’t spoken much to his teammates after returning to Douglas. It’s not that he didn’t care what they thought; rather, he knew that this was a decision he had to make on his own and didn’t want any of his friends trying to talk him out of it.

On February 20, 2008, Barnicle received a one-word text: “LetsRun.com.” He quickly pulled up the LRC homepage on his browser to find Cormier had Quote of the Day status:

“I enjoyed every minute of it. I had a chance to meet a lot of really neat people and run at a very competitive level…To be a really good runner it’s something you have to eat, sleep and breathe. I can honestly say I don’t have that anymore… [Joing the Marines] is something I’ve always wanted to do. I’ve always wanted to serve my country. Considering everything that has happened to me I feel very lucky this door opened up.”

Barnicle had heard from a friend the night before that Cormier was joining the Marines. Now he had the proof.

“It didn’t really surprise me,” Barnicle said. “I was really just hoping that Kenny would be happy because he clearly wasn’t happy during his last four to five months at Arkansas — running, getting his ass kicked and not really being able to do what he wanted to do.”

A Standout In The Marines

Cormier’s next few years were a whirlwind. He finished his basic training by August of 2008. Never one to take the easy path, Cormier decided to become a scout sniper and enrolled in the 3rd Marine Division Scout Sniper School in Oahu in January 2009 (he didn’t finish college and enlist as a commissioned officer because officers cannot be snipers). He deployed to Afghanistan’s Helmand Province two months later as a lance corporal.

“I wanted to see if I could become a sniper because it’s such a demanding position in any military service, especially the Marine Corps,” Cormier said. “I wanted to be part of the most elite group I could be.”

Just as he did at Arkansas, Cormier, now going by Ken, left an immediate impression.

“He was a guy that stood out definitely,” said “Scarecrow,” who served with Cormier in the 3rd Division Scout Sniper Platoon (Editor’s note: “Scarecrow” asked us not to use his real name but instead use “Scarecrow” as his current job security could be compromised by revealing a connection to Cormier). “Whenever you get somewhere new and walk into a room, you can tell the guys that stand out and he was definitely one of those guys. I made it a point to get close to Ken and soak up as much as I could from him. If he wasn’t the most physically fit, he was in the top two. And on top of being physically fit, he was very knowledgeable about the skillcraft of being a sniper.”

Cormier knew that to be an effective sniper, he had to put on weight. Sniper missions can last for several days and require carrying backpacks, flak jackets and lots of food, water and ammunition — not to mention three weapons. It can add up to more that 100 lbs. of gear per person. Cormier’s up to around 210 lbs. now, compared to his running weight of 145. Though he traded in lifting weights for running miles, Cormier’s endurance base remained, built up over years of high mileage.

“The high standards within the Scout Sniper community mean that the attrition rate is high, and those that pass the demanding schooling are physically and mentally at a higher level,” said “Nitro,” who also served in the Scout Sniper Platoon with Cormier (and also asked that his real name not be used for the same reason as Scarecrow). “Ken was a level beyond that. Having trained side by side with Ken, I can attest that he is one of the greatest all-around athletes I have worked with. Whether it was his raw strength, or running abilities, Ken was above and beyond most.”

Physically dominant, Cormier never brought up his running accolades. Occasionally people would ask him about his running background and he would explain that he ran a bit in college. Few knew that he was a national champion in high school and one of the top freshmen in the NCAA.

Cormier described his deployments — he returned to the States in October 2009 and deployed to Afghanistan again from December 2010 to June 2011 — as a grind. It’s seven months of working seven days a week and as usual, Cormier worked as hard as he could. When a sniper goes overseas, he has the option of volunteering to attach himself to a “grunt” unit — normally an infantry unit — and provide support.

“Ken was one of the guys who would raise his hand almost every time,” Scarecrow said. “It was unreal — and this was in an area where guys wouldn’t always volunteer because it was so hot.”

Cormier’s modesty and friendliness won over the other members of his squad. He made sure to remember the names of their friends and family and went out of his way to help new members of the platoon get adjusted, especially with physical fitness.

“He enjoyed being out there all the time with his brothers to the left and right of him, almost like he was protective of them,” Scarecrow said. “Every guy in our platoon, he considered his younger brother. And my personal opinion of why he volunteered so much wasn’t only because he was good at his job, but that he really cared for the guys to his left and right and wanted to make sure they came home to their families.”

Regular sniper missions were generally performed with eight-man teams. The team would insert at night, sometime walking up to 15 miles to the target location while lugging all of the gear. After arriving at the location, the team would settle on a hide site, which could be an abandoned house or a tent on the ground, and wait for their target. Each team member had a specific role, such as spotter, shooter, radio operator, or security for the camp/building.

“Ken was one of the primary guys on the gun,” Scarecrow said. “If there was a target, he was one of the first guys to engage. I can’t tell you specifically how many gunfights he got in or how many kills he got, but he did his job over there. He did what he had to do to protect himself.”

Cormier enjoyed his deployments, but he’d still think about his friends from Arkansas.

“I remember being in Afghanistan about the time I was supposed to graduate college, getting some emails from my buddies as they were graduating or running at NCAAs,” Cormier said. “I just remember being over there and seeing how vastly my life had changed in a very short period of time. I really enjoyed the idea of things changing and experiencing new things in life.”

After returning from Afghanistan for the second time, Cormier’s unit deployed to the South Pacific, traveling to Australia, Okinawa, Indonesia and many other islands from 2011 to 2012. The travel was nice, but Cormier was no longer excited about being in the military, which was going through a drawdown. He wasn’t being deployed to combat zones and knew that if he went to the private sector, he’d have more control over where he was and what he did. It was time for another change. In February 2013, Cormier left the Marines and joined a private military company overseas.

That’s still what Cormier does now, protecting major assets of big-time corporations. That job description is specifically vague, because it can range from escorting a VIP to a facility, guarding an oil rig, providing security on an American-owned building or even assisting the Secret Service. Even though he’s overseas for 10 months a year, he is extremely pleased with his life. He has the freedom to do what he wants to do when he wants to do it and the money is much better than it was in the military. When he is at home, he usually visits his parents back in Douglas and his girlfriend, Monica Parodi, a dietician in the Dallas area, whom he says is “amazing” to put up with his job.

Cormier also make sure to meet up with his buddies from Arkansas once a year, occasionally helping those in a financial bind attend the reunion.

“When I see the guy, he just looks like the picture of happiness and bliss,” said Cobrin, his former Arkansas teammate. “He looks like he’s moving through life doing exactly what he wants to do. I see Kenny very happy and in a good mental place. Maybe in 2010 or 2011, I didn’t know that. I was like (thinking), ‘Kenny was at war, he might come back messed up,’ but the last two years, when I’ve seen him, he’s seemed great. Seeing him at those times has been the highlight of my year.”

“They said he’s going to come back and be a different person, but when he comes home and visits, he’s the same kid he was in high school and college.”

Throughout his life, Cormier has found it easy to adapt to a new lifestyle. That hasn’t always been the case with his Arkansas teammates. Barnicle ran professionally for a few years after exhausting his collegiate eligibility in 2010 (he ran at the University of New Mexico as a graduate student after finishing at Arkansas), amassing pbs of 13:36, 28:10, 62:43, and 2:21:58. It took him a while to realize that his heart wasn’t in the sport anymore and he looked at Cormier as an example of someone who was able to leave running behind and put that energy to use in another career.

“Kenny taught me more than any of my friends about looking forward to other things and life outside of running,” Cobrin said. “He made a decision, was resolute and sound about it, and he’s had huge success.”

Cormier does run a little bit these days to stay fit for his job, but it’s not the same as when he was competitive.

“I think one of the reasons I don’t enjoy running any more is how good I was at it,” Cormier said. “Getting out now and running three miles is an ordeal. Before, I’d roll out of bed, put on shoes, run six to eight miles as a morning run with the guys and think nothing of it.”

Still, Cormier is grateful for the sport for the friendships the sport has brought him and the sense of community running offers. Cormier has remained out of the public eye since his decision to join the Marines, but he agreed to speak to me for this story because he always liked the job LetsRun.com did of uniting the running community and wanted to be able to share his story with the runners and fans that supported him during his career.

Runners approach Cormier now and then asking whether they should quit the sport like he did. He always tells them the same thing: there are no right or wrong choices in life when it comes to direction. Cormier could have gone down a thousand paths after high school, and would have been equally happy with all of them because he’d still be the same person underneath.

“I have some very close friends who had been in the military who had experienced being in combat and [they] tried to advise me in what to look for [in Kenny]” Kenny’s father, Ken Cormier, said. “They said he’s going to come back and be a different person, but when he comes home and visits, he’s the same kid he was in high school and college. He enjoys the situation he’s in and makes the most of it and has a way of being contented with the decisions he’s made and what he’s doing.”

Kenny is our December 2014 Blue Collar Runner of the Month. Anyone who runs 120 miles a week and makes himself into a Foot Locker champion off of hard work is blue collar.

Discuss the article on our world famous messageboard: Finding Kenny Cormier – We catch up with the 2004 Foot Locker champ 10 years after his victory. Our main forum (which has everything) is here but we also have a high school only forum.

Cormier On LetsRun Through The Years:

2004: LRC Homepage A Few Days After Cormier’s Foot Locker Win

2004: MB: Ken Cormier busted 120 miles a week in the summer.

2005: MB: Cormier to Ark

2005: MB: Who will win Arcadia Boys 2 Mile

2005: MB: Best Frosh at Pre-Nats

2005: MB: Top Frosh at NCAAs

2007: MB: Is Cormier running Track?

2008: LRC Homepage the day Cormier’s Marine announcement came out

2008: MB: Kenny Cormier joins the U.S. Marines!

2009: MB: Kenny (The Bear) Cormier

Outside Coverage of Cormier:

2004: Men’s Racing Q&A with him in after FL win

2008: Hometown paper after Cormier decides to join the military

Editor’s note: The original version of this article included the name of the nurse practitioner at Arkansas. We’ve removed it as we don’t feel it really adds anything to the story and medical privacy laws could make it hard for her to respond.