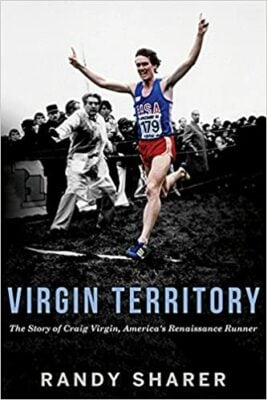

“Virgin Territory” Book Excerpt, Chapter 17: Front Runner Inc.

Last week, LetsRun.com honored the 40th anniversary of Craig Virgin’s victory at the 1980 World Cross Country Championships in Paris — four decades later he remains the only American man to win World XC. We had an exclusive interview with Virgin, who recalled his victory in great detail.

Now we’re pleased to present, exclusively on LetsRun.com, the second of two excerpts from his authorized biography, Virgin Territory, which was initially released in 2017. You can read chapter one in its entirety here. Below is chapter 17, which addresses 1980 World XC and the US boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow (Virgin won the 10,000 meters at the US Olympic Trials). You can order a copy of the book, autographed by Virgin, here.

By Randy Sharer

March 17, 2020

A World Cross Country title “is worth Olympic gold medal status in my mind, but unfortunately it’s not known in America.”

— Bill Rodgers

An increasing number of invitations from road race directors came Craig’s way in the fall of 1979. He could ask for and receive several thousand dollars to appear and it didn’t matter how well he ran. Accepting the money without jeopardizing his Olympic eligibility became a growing concern.

An increasing number of invitations from road race directors came Craig’s way in the fall of 1979. He could ask for and receive several thousand dollars to appear and it didn’t matter how well he ran. Accepting the money without jeopardizing his Olympic eligibility became a growing concern.

Craig didn’t like that his $12,000, one-year contract with adidas had to be filtered through the St. Louis Track Club. He felt the deal was too restrictive. He saw that Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers had created running apparel companies. “That’s when I came up with the idea of having my own company in sports marketing, promotion, PR and being a consultant so that I could hire out,” Craig said.

Craig named the company Front Runner Inc. to reflect his racing style and present a positive image to clients. Race directors would hire Front Runner and Front Runner would assign Craig to do the marketing, consulting, promoting or public relations work. Front Runner would get a check and pay Craig.

Before beginning, Craig sought the approval of AAU president Ollan Cassell, who had the power to revoke Craig’s Olympic eligibility. Cassell flew in with a contract to get everything about this revolutionary idea in writing. He’d approved Hilton Hotels paying Shorter in April of 1979, which made Cassell believe Craig’s idea could work, too. Under Shorter’s deal, Hilton paid the AAU $25,000 and paid Shorter as a consultant for its physical fitness program. “Craig did a different kind of thing,” Cassell said. “He wanted to promote events and he wanted to run in them, so that’s the reason I came down to his house.”

Cassell looked at Craig’s educational background as a radio and TV major who took marketing and advertising classes. If there was ever a challenge to Craig’s international eligibility, Cassell could defend him by saying “he was qualified” to do promotional events. “That’s the reason we approved him to use his name and his athletic ability and everything else in promoting races,” Cassell said. “Craig was a pioneer. There is no question about that.”

In the March 1980 issue of Runner’s World, Craig told writer Amby Burfoot, “I think an amateur athlete should be entitled to be an entrepreneur in whatever way he can. If a guy has the determination, the hustle, the gumption, then he’s entitled to whatever he can scare up.”

As Craig’s first adidas contract was about to expire, Spalding approached him about helping to develop a line of running shoes that he’d endorse. Spalding offered a multiyear contract worth $50,000 to $60,000 a year. The four American distributors of adidas told adidas headquarters they wanted Craig to remain as their spokesperson. So Horst Dassler, son of adidas founder Adi Dassler, flew Craig first class to Europe to negotiate a new multiyear contract.

What they came up with was a five-year deal that included a two-year option. Craig would be paid $30,000 to wear adidas shoes and apparel in 1980 and the amount would escalate each year. The penultimate year would pay him $60,000 and the last year $70,000. “As far as I know,” Craig said, “at the time that was the longest-term contract anybody had ever signed.” He’d later realize long-term contracts had positives and negatives.

Science of Success

When it came to running, Craig planned to spend September recovering. The first week, he wasn’t supposed to run at all. The next week called for four miles a day. The third week, he’d run four in the morning and four in the afternoon. The fourth week, he’d cover four in the morning and six in the afternoon. However, he raced five times that month. Many of Craig’s “low-key” races became showdowns with top regional runners looking to make a name for themselves.

The science behind Craig’s running success had been a mystery until he underwent testing at the physiology lab at the University of Illinois in 1975. Among the things measured was his maximum volume of oxygen consumption (VO2 Max). His score of 84 was double the average for a man his age. “They were actually scared to publish anything,” Gary Wieneke remembered. “They didn’t think anybody would believe that somebody could be that good.” The head of the lab also told Wieneke that Craig lacked flexibility. Wieneke told the scientist, “Regardless of what your test said, this guy can run.”

Craig was tested again at the Cardiac Research and Rehabilitation Lab at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis on September 13, 1979. Among the first tests was a check of his resting pulse rate, which was 41 beats per minute. That was below the average of 45 to 47 for an elite runner. Craig’s resting blood pressure was 100 over 67, slightly below the average of 112 over 75 for an elite marathoner. An echocardiogram revealed his heart to be exceptionally large for someone his size. He then did three submaximal runs of three minutes each on a treadmill. The results showed his oxygen consumption was less than other elite runners including Frank Shorter.

The September issue of Runner’s World included a story written by Craig about the benefits of cross country and how to train for it. “One would think that the so-called ‘running boom’ in this country would have had a positive spin-off effect on cross-country,” Craig wrote. “I personally don’t think cross-country has yet felt the impact.” Among the points he made: “Cross-country deserves better attention than it receives in the United States. The sport of cross-country has always been regarded as track and field’s poor cousin in our country.”

The civic leaders of Lebanon didn’t want Craig to be poor when it came to Olympic training funds, so they had him organize a four-mile road race in conjunction with the annual Lebanon Fall Festival. Proceeds from the race and festival would go into a savings account to help defray his training expenses. Adidas, which donated shirts and banners, flew in a rep to help organize the race, which drew more than 300 runners. Craig won the October 6 event in 19:07 on a course that became one of his favorite training routes.

Throughout his career, Craig had found most of his fame far from Lebanon, but in early November fame followed him home. Grete Waitz, who held the women’s marathon world record, and her husband, Jack, visited the Virgins’ farm and stayed overnight at the home of Grandmother Putt. The adidas-sponsored Waitz went for a few training runs with Craig around Lebanon.

The focus of Craig’s training that fall was the December 2 Fukuoka International Marathon in Japan. The adidas distributor for Japan had asked him to enter. There was also the fact he needed a qualifying time of 2:21:54 or better to enter the US Olympic Trials in case he decided to double in the 10K and marathon instead of the 5K and 10K.

Traveling across 16 time zones to Fukuoka—a city of over a million people in southern Japan—“was a long-ass trip,” according to Craig, who arrived the Wednesday prior to the Sunday race. The event was founded in 1947, but didn’t become an international race until 1965. In 1979, it also served as Japan’s qualifying race for the 1980 Olympics. “They didn’t pay us money,” Craig recalled, “but they treated us like celebrities.”

Visiting entrants were each provided with an interpreter. Craig shared a room in the Nishitetsu Grand Hotel with Canada’s Brian Maxwell, who’d later invent the PowerBar. The 112-man field included defending champion Toshihiko Seko of Japan, Bernie Ford of Great Britain, 1976 Olympic champion Waldemar Cierpinski of East Germany and Japanese twins Shigeru So and Takeshi So. Athletics West had four entrants including Tony Sandoval.

The race began with 2 1⁄2 laps on the track in front of a capacity crowd at Heiwadai Stadium, which also served as the finish. The flat course following the peninsula around Hakata Bay was lined by a half million fans. Craig was in a tightly bunched pack of 30 when he passed

10K in 31:00.

Craig had hoped to race in custom-made adidas Marathon 80 shoes, but they didn’t arrive in time. He was concerned his other racing shoes were too wide. “I wanted more support,” he said. “So I did an old track trick—I went down a half a size. Instead of 9 1⁄2, I wore size 9. Well, that works in spikes in a short distance. I didn’t realize how much your feet swell in the course of a marathon.”

At about 10K, not long before Craig’s feet began to suffer, he was tripped from behind and somersaulted to the pavement, leaving behind more skin than he cares to remember. Luckily, he soon regained his spot in the pack. “I’m not sure it wasn’t Toshihiko Seko that tripped me,” said Craig, who passed halfway with a slight lead in 1:05:13.

Craig hoped his feet could be saved by adjusting his stride and foot plant. Hope turned to hell as blisters began to form. By 25K, he had dropped 10 seconds behind Seko, the So twins, Ford and New Zealand’s Kevin Ryan. At 30K, Craig abandoned thoughts of a fast time and focused on getting under the Olympic Trials standard. “It turned out to be the toughest seven miles I have ever run,” wrote Craig in a story for the February 1980 issue of The Runner.

Craig hung on for 17th in 2:16:59, well under the Olympic Trials qualifying standard of 2:21:54. “I remember my feet were just bloody,” said Craig, who asked for his shoes and socks to be cut off. The 23-year-old Seko won in 2:10:35 after outkicking Shigeru So (2:10:37) and Takeshi So (2:10:48). The fourth-place Ford (2:10:51) made it the first marathon with four men under 2:11.

AAU Roadblock

Craig was later shocked to learn Fukuoka’s precisely measured course, which rivaled Boston’s and New York’s in prestige, wasn’t sanctioned by the AAU, which didn’t accept his qualifying time. “I may have to run another one,” Craig told Woods. “Personally, I’m upset about the thing. I don’t think I’m being treated fairly in the situation. It’s a slap in the face of the Japanese if they [AAU officials] think it’s not a creditable course.” Craig appealed the ruling and his time was accepted.

As 1979 came to a close, Craig was named the US Distance Runner of the Year by Runner’s World. He was so filled with confidence he hardly noticed on December 24 that the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan. A story by Woods in mid-January of 1980 included Craig’s opinions about the possibility the United States might boycott the Moscow Olympics to protest the Soviet invasion. Craig prophetically believed a boycott would hurt the prestige of the Olympics and sow the seeds of a Communist boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. He considered the Olympics one of the best ways to strengthen international relations. “For the most part, the athletes will keep on training and racing and the politicians will keep on ranting and raving,” he told Woods. “Myself, I don’t anticipate a boycott.”

Craig returned to Eugene on January 19 for the US Cross Country Trials where the top nine would qualify for the March 9 World Championships in Paris. He stayed out late the night before, renewing friendships from his days at Athletics West and Stretch & Sew. The impact of only five hours of sleep was lessened by the fact the race started in the afternoon. Dan Dillon led the first five miles of the 7 1⁄2-mile race until Craig took over and created a 150-meter gap to win in 36:43.7. “I knew after one lap [two miles] that it was going to be a super day for me,” Craig told the media. “I’d very much like to be the first American to win the international meet.”

A week after racing in the 40-degree chill of Eugene, Craig was in the adidas-sponsored Bermuda International 10K Road Race. “To go there for three to five days was a real break weatherwise,” said Craig, who fondly remembers filling free time with moped races against fellow runners. During the fifth mile of the actual race, he surged away from Herb Lindsay, Bruce Bickford and Jon Sinclair to win in 29:17. Craig might have run faster except he needed to save something for the following day’s half marathon in New Orleans, put on by St. Louis-based Anheuser-Busch, a sponsor Craig wanted to please. “You can get in a compromised situation with sponsors,” said Craig, who contested another half marathon in San Blas, Puerto Rico, to please adidas a week after New Orleans.

Craig arrived at the starting line in San Blas wearing an adidas singlet with SEGO written across the chest. Sego was the diet food drink he’d worked for at Pet Inc. It was his first rematch with Miruts Yifter since the World Cup. Heavy rain taught Craig that the hard rubberized

compounds of his adidas Marathon 80 shoes didn’t grip the pavement properly. Despite slipping every step, he managed to outkick Lasse Viren for third in 1:04:28. Yifter, cheered on by 150,000 spectators, finished 32 seconds ahead.

In February of 1980, Craig revealed Front Runner had signed a one-year deal with the International Management Group (IMG), headed by super-agent Mark McCormack. The deal involved Craig advising IMG about the pros and cons of business opportunities in road racing and track and field. “I wouldn’t term this an athlete/agent relationship,” Craig told Track & Field News. “This is a business arrangement between my company and IMG. They will be assisting my company in finding new opportunities and will offer expertise in doing business in

the Big Leagues.”

IMG, which signed mile world record holder Sebastian Coe at the same time as Craig, wanted more than a one-year deal, but Craig was hesitant to make a longer commitment. “I said, ‘Show me what you can do the first year,’ because I was really concerned,” he said. “I had plenty of things coming in. I had more than enough on my plate with what was coming in on the phone. There was only one of me and all these opportunities. The situation was that was a tumultuous time in American distance running just when I was hitting my peak.”

Bone Chilling

Craig’s last tune-up for the World Cross Country Championships was the March 2 Bran Chex 10K Road Race in St. Louis. He beat Don Kardong by 1.9 seconds in 29:37.7, but the five-degree chill—the coldest March 2 in St. Louis in 67 years—may have played a role in Craig straining his left hamstring. He visited his chiropractor cousin later that day for therapy. Within two days, Craig was on his way to West Germany for a three-day stay at adidas headquarters.

Kenny Moore of Sports Illustrated would later write of the US cross country team’s pre-World Championships bonding and note:

The only regret was that Craig Virgin, the winner of the U.S. men’s trials, was not yet in Paris to enjoy the prerace idyll. He had recently founded a consulting firm and was in Germany speaking with a shoe manufacturer. An ambitious man, comfortable with the ways of promotion, Virgin is intent on taking full advantage of his success, and thus differs somewhat from the balance of the team, for whom the camaraderie of such a trip and the competition itself are reward enough. While not resented, Virgin’s forceful drive gave rise to wishes that he relax a little. Virgin himself admits to feeling “pulled at” by the demands of running and business, but says, “I’ve been training really hard. Let’s let this race decide if I’m holding together.”

The IAAF began governing the World Cross Country Championships in 1972 when 15 countries took part. The race was founded in 1903 in England when 41 runners from four countries competed. The “countries” were England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The race attracted its first “overseas” squad in 1907 when France entered. Tunisia was the first African entrant in 1958.

Prior to 1980, the best American male results were third-place efforts by both Tracy Smith in 1966 and Bill Rodgers in 1975. The day before the World Championships in Paris, Craig ran eight miles on the course, studying the final 800-meter straightaway in particular, taking note of landmarks “for gear change No. 1, gear change No. 2 and then, if necessary and possible, a final Hail Mary gear change.” A trainer later treated his left hamstring and back, but overall he felt good.

On the bus ride to the starting line, Craig psyched himself up by listening to Linda Ronstadt, Billy Joel and Neil Diamond on the Sony Walkman he’d bought in Japan. The technology was so new, it wasn’t meant for export, a fact made clear by the Japanese writing on the case.

The 190 entrants went to the starting line anxious to secure a good position early, which made the ensuing false start of little surprise. Unfortunately, not everyone was ready for the restart when the gun fired again. Most countries went with two men at the front of the starting

box, but the ever-democratic Americans wanted as many men in the first and second rows as possible. “I was getting them set up and the starter never said ‘ready’ and he never said ‘set,’” Craig recalled. “He just shot the gun off. My own guys ran me over and nearly took me down.”

Someone prevented Craig from doing a face-plant, but by the time he got moving, he was encased in the field. A teammate, Dan Dillon, grabbed the lead as the field began the first of five 2,450-meter laps. England’s Nick Rose took over while climbing the backstretch hill on the second lap, quickly creating a 30-meter gap on defending champion John Treacy of Ireland in second.

During the second lap, Craig went from 25th to ninth, but Rose stretched his lead over Leon Schots of Belgium in second. During the third lap, Craig reached the back of the chase pack and his second moment of truth, as detailed in chapter one. He answered that moment of truth and two later ones in the only way that could produce a thrilling come-from-behind victory. Spectators then and viewers of the race video now get caught in a vortex where Craig’s imminent defeat turns into assured victory. The process is gradual at first, but suddenly becomes something Hollywood would reject as unbelievable.

(LRC note: You can read all about Craig’s win and watch it in Chapter 1 here)

Faint Fanfare

American fans, focused as they were on domestic professional sports, paid little attention to Craig’s win. The few who heard of his triumph had trouble appreciating its importance. Top US runners, however, knew what Craig had done. “It’s worth Olympic gold medal status in my mind,” said Bill Rodgers, “but unfortunately it’s not known in America.” At the postrace dance, champagne flowed. Moore wrote in Sports Illustrated that as Craig surveyed the excitement, he said, “I wonder if the people back home will ever be able to fully appreciate this. Here I’ve been exposed to 50 million Europeans on TV today, but in my own country I’m sure I’ll only draw modest attention.”

Moore noted: “To many runners that would be a source of relief, but Virgin seemed concerned.” Craig later went out on the town with Fred Lebow, the New York City Marathon race director, who was hoping to host the 1984 World Cross Country Championships. Joining them was Kathrine Switzer, the first “numbered” female finisher of the Boston Marathon in 1967. [Roberta Gibb ran without a number in 1966.] “I didn’t get back to the hotel until 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning,” said Craig, who caught an early flight to adidas France headquarters in Strasbourg for a press conference. The media wanted to hear Craig’s stance on the US threat to boycott the Moscow Olympics.

Every Olympic-year World Cross Country champion prior to 1980 had gone on to win an Olympic medal. “My ambition this year is to go to the Olympics and I’m planning to go with some other athletes to Washington to meet President Carter to persuade him to change his attitude towards the Games,” Craig told reporters. “I don’t condone what the Soviet Union has done in Afghanistan—make no mistake about that. But the Olympics is still something worthwhile. I appreciate there is good and bad in them, but I think it’s important contact between sportsmen and should continue.” The can-do attitude that had served Craig so well for so long was about to meet its match.

Back home, the combination of Craig’s fame and oratory skills made him a highly sought speaker for club luncheons and school assemblies in the St. Louis metropolitan area. Every time he spoke in early 1980, people asked his views about the possibility of an Olympic boycott. Callers to his 15-minute radio show about running and fitness on KMOX in St. Louis wanted to know the same thing. “I knew the history of prior Olympic boycotts and other types of demonstrations and knew there was nothing that we were proposing to do for Moscow that would make a concrete difference,” said Craig, who’d disapproved of Moscow being chosen to host the Games years earlier. “If somebody could have shown me or told me how it was going to make a difference to the people of Afghanistan or to the people in Russia, then I would have gladly considered the sacrifice.”

President Jimmy Carter set February 20 as the deadline for Soviet troops to withdraw from Afghanistan or else the US would boycott the Moscow Olympics. The date zoomed past without the slightest compliance by the Soviets.

In an April 21 interview with the Daily News of Rolla, Missouri, Craig said, “The only way we can stop Russia from marching over little countries is by military force. Having an Olympic boycott to stop military action is like throwing a glass of water on a burning house.”

Among US athletes, support for the boycott was split. Those opposed to it denounced Soviet aggression, but didn’t agree a boycott was an effective way to punish the Soviets. “I don’t think President Carter understood the full implications, either, or he would have understood it

was as much a punishment for America as it was for the Soviet Union,” Craig said.

Business as Usual

The Carter administration claimed a boycott would show the Soviets they couldn’t commit aggression and expect to do business as usual. The odd thing was most business did not continue as usual. There was no interruption in trade between the two countries except grain and technology embargo initiated in January of 1980 and discontinued 15 months later by Ronald Reagan. Other sporting events between the countries in boxing and even track and field were held as scheduled. American tourists continued to visit the USSR. In essence, everything

except the Olympics went on as usual. The anti-boycott crowd believed that—short of using military action—the USSR couldn’t be punished more than when the United Nations condemned its invasion of Afghanistan.

Athletes in favor of the boycott were sure it would make the Soviet people aware of their government’s violations of international law. That was a leap of faith considering the Soviet citizenry got its news from state-controlled media. Few Soviet athletes in the 1980 Winter Olympics held in February at Lake Placid, New York, had even heard of the boycott threat. Track & Field News came out against the boycott and suggested a better way to protest would be to skip the opening ceremonies. The Athletes Advisory Council to the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) also suggested boycotting the medal ceremonies. Craig liked such ideas and even suggested athletes protest by wearing black armbands.

President Carter claimed the boycott was necessary for national security. The USOC is not legally bound to comply with a president’s wishes, but President Carter said he’d take legal actions to prevent the USOC from sending a team to Moscow. He also said participating in the

Olympics would have validated Soviet aggression.

USOC delegates met in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on April 12 to consider three options. They could vote to send a team to Moscow, delay the decision until May 24 (the last day for entering the Olympics) or they could agree to the boycott. If there was a boycott, some hoped the International Olympic Committee would change its rules to allow athletes of boycotting nations to compete “unattached” under the Olympic flag.

In a maneuver some viewed as blackmail, the Carter administration threatened to cut a $16 million federal grant to the USOC. The administration also asked Sears to withhold a $25,000 pledge to the USOC until it voted to boycott. As noted by Nicholas Evan Sarantakes in

his book Dropping the Torch, Sears and 14 other major corporate donors agreed to withhold a combined $175,000 in pledges. The White House also vowed to revoke the tax-exempt status of the USOC. Carter sweetened the deal by offering to cover the deficit from the Lake Placid Winter

Olympics and help fund the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics. Vice President Walter Mondale told USOC delegates before they cast their ballots that “history holds its breath, for what is at stake is no less than the future security of the civilized world.” Delegates voted to boycott, 1,604 to 797.

Speaking Out

Craig was livid, but he’d seen it coming when NBC announced a week prior to the USOC vote that it wouldn’t televise the Olympics. He’d seen in 1972 and 1976 that the nation fell in love with Olympians when TV played matchmaker, but now the matchmaker was dead. Craig was so disgusted with The Athletics Congress (TAC replaced the AAU as track’s national governing body in 1979; TAC changed its name in 1992 to USA Track and Field) for not standing up for athletes and negotiating with the White House, he returned a $200-a-month stipend because he didn’t want to feel beholden to TAC.

Craig’s anger attracted national attention when he said, “US athletes have been sold down the river for a bag of gold. Carter bought himself a boycott by putting a gun to their [USOC delegates’] heads.” Craig’s reaction drew hate mail. One letter read: “If you love the Russians so much, why don’t you go there to live?” Craig bristled at the suggestion he was unpatriotic for disagreeing with the president. “Congress disagrees every day with the president, and they’re not considered unpatriotic,” he told Tom Jordan of Track & Field News. The ever-optimistic Craig held out hope through May for US participation in the Olympics. By June, his hope was gone.

Craig came to believe his opposition to the boycott was shared by many athletes, who didn’t possess his courage to speak out. In the June 6 edition of the Los Angeles Times, Craig told writer Mark Heisler, “There weren’t enough athletes who had the guts to stand up for what they believed in. A lot of this I blame on the athletes. Many athletes were too wishy-washy. They were too afraid to say what was on their mind. At this point, the ones who didn’t, I don’t want to hear any bitching [from them] in several weeks, because if they weren’t willing to say something at the time it needed to be said, then they deserve to not have an Olympics.”

The sad numbers of the matter showed that 466 American athletes and those of 65 other nations boycotted while 5,512 athletes from 81 countries participated. Of the 466 Americans, 219 never made another Olympic team.

Athletes fell into two categories after their Olympic dreams were destroyed. “It drove some on and others just gave up emotionally and mentally,” said Craig, who remained emphatically among the driven. He continued to train and race as planned to peak during the Olympics between July 21 and August 1. He knew he’d get another Olympic shot in 1984, but felt sorry for athletes who’d be too old by then. Craig soldiered on, but not without scars. “When they took us out of the Games,” he told the Oregonian, “they removed the one, sole goal that my

life has revolved around for the last three years.”

Excerpt from Virgin Territory: The Story of Craig Virgin, America’s Renaissance Runner by Randy Sharer, the authorized biography of Craig Virgin. Used with permission. You can order a copy of the book, autographed by Virgin, here.