“Virgin Territory” Book Excerpt, Chapter 1: Playing It Risky – Craig Virgin’s 1980 World Cross Country Win

Last week, LetsRun.com honored the 40th anniversary of Craig Virgin’s victory at the 1980 World Cross Country Championships in Paris — four decades later he remains the only American man to win World XC. We had an exclusive interview with Virgin, who recalled his victory in great detail.

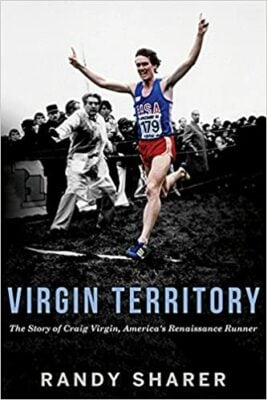

Now we’re pleased to present, exclusively on LetsRun.com, the first of two excerpts from his authorized biography, Virgin Territory, which was initially released in 2017. Below, chapter one details Virgin’s win at the 1980 World XC as well as his upbringing in Illinois and his struggle with kidney and urinary tract problems as a child. You can order a copy of the book, autographed by Virgin, here. (Unfortunately, the book is not available as an e-book).

We’ve also released an excerpt from Chapter 17, which addresses Craig being a pro runner while pretending he wasn’t and the US boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow (Virgin won the 10,000 meters at the US Olympic Trials).

By Randy Sharer

March 16, 2020

“There are moments of truth in every race . . . sometimes several. How you react will determine your destiny.”

— Craig Virgin

The cause seemed lost from the start. For one thing, Craig Virgin was a 24-year-old American in a footrace no American had ever won. For another, he’d suffered a leg injury a week earlier that had hampered his training. Great finishes, however, owe their memorability to the tension of adversity. Craig had been given a chance to be great—or instantly forgotten—in the March 9, 1980, International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) World Cross Country Championships in Paris. The race was the all-star game of distance running as it brought together the world’s best from the mile to the marathon. Most entrants were older than Craig, but he’d been ahead of his time for years during a relentless march from 14-year-old prodigy to US Olympian.

The cause seemed lost from the start. For one thing, Craig Virgin was a 24-year-old American in a footrace no American had ever won. For another, he’d suffered a leg injury a week earlier that had hampered his training. Great finishes, however, owe their memorability to the tension of adversity. Craig had been given a chance to be great—or instantly forgotten—in the March 9, 1980, International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) World Cross Country Championships in Paris. The race was the all-star game of distance running as it brought together the world’s best from the mile to the marathon. Most entrants were older than Craig, but he’d been ahead of his time for years during a relentless march from 14-year-old prodigy to US Olympian.

Before the gun fired for the 7.2-mile (11,590-meter) event, the field of 190 antsy runners from 30 nations false started, negating Craig’s excellent getaway. Officials controlled the runners with corralling ropes 150 meters out. When the gun went off again, Craig was facing the wrong way and fell. “I remember somebody grabbing me, and that kept me from going all the way down on my face,” he said. “By the time I got my balance and took off, there was just a wall of humanity in front of me.” It was enough to make Craig want to give up. He’d later describe his decision to forge ahead as the first of four “moments of truth” in that race.

The leaders passed the first uphill 800 meters at almost a four-minute-mile pace despite running on shaggy turf at the Longchamp Hippodrome, a famed horse-racing track. On the second of five laps, each of which measured 2,500 meters and included two sets of steeplechase barriers and a stack of wooden logs to hurdle, Nick Rose of Great Britain, the rival Craig respected more than any other, boldly set off to run away with the race. Craig , who began the second lap in 31st, swerved through traffic like a race car driver to climb into 25th. He could see the leader and recognized the loping stride of Rose, a Western Kentucky University alum who’d finished second to Craig in the 1975 NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) cross country meet, but had beaten Craig in six other races since 1973.

If knowledge is power, then Craig’s understanding of Rose as a man and a runner was indeed an asset. Craig knew Rose was a versatile tactician, who could win by setting the pace or by using his sub–four-minute-mile speed to finish with.

By the end of the second lap, Craig was ninth. At halfway, Rose still enjoyed a 70-meter lead over 1977 champion Leon Schots of Belgium. Even a collision with photographers on the second lap hadn’t slowed Rose. Craig joined Schots and Aleksandr Antipov of the Soviet Union in the group chasing Rose on the third lap.

At that point, Craig had to weigh the pros and cons of drafting off others in the shelter of the chase pack versus setting off on his own to catch Rose. Craig’s life to that point made the answer clear. He’d been inspired as a youngster by Frank Shorter’s victory in the 1972 Olympic marathon, which didn’t mean settling for second. Likewise, following in the footsteps and breaking the records of his hero, Steve Prefontaine, wouldn’t allow Craig to play it safe. Ever since he’d begun running 11 years earlier and set his first national age-group record, Craig had been on a relentless path of improvement. While the careers of others were derailed by obstacles both physical and mental, Craig had survived to reach a second moment of truth. The rhetorical question he asked himself was, “Did I come 3,000 miles to run for second place or did I come 3,000 miles to try to win?”

Craig had to go.

On the fourth lap, he sliced Rose’s lead from 40 meters to 20. With a lap left, Rose passed 10K in 29:25, but looked tired. He glanced over his shoulder and saw Craig’s proximity. Rose reacted by surging, a discouraging sight for Craig. On the last backstretch, which featured a 400- meter incline that rose 10 meters, Craig was rejoined by Schots, Antipov and West German Hans-Jürgen Orthmann. “I forced myself to stay on their shoulder or a step ahead over the next half mile, and during that half mile, I was able to recover,” Craig recalled of that third moment of truth.

Play-by-Play

With 900 to go, Rose dug deep, but the energy he sought had already been dispensed, a fact yet to be detected by the commentator on the British television broadcast. The transcript of his race descriptions should be read with a British accent as well as a gradually ascending vocal

pitch and level of excitement.

Half a mile to go and the challenge is vanishing.

Virgin trying to get away. Orthmann trying to get away. Nick Rose will have none of it.

And the English that were here and were in the stands have gone down to the side of the track to cheer him on, the Bristol Boy.

And what a record it will be. American cross country champion. British cross country champion and, if he holds on to this lead, international and world cross country champion.

Look at that, it has closed once again. Virgin trying a burst. Nick Rose, head down. Orthmann leading the charge. The West German leading the charge now. Orthmann, who’s got finishing speed.

This really is pulsating.

Orthmann of West Germany. Hans-Jürgen Orthmann, the 25-year-old, who beat us in indoor track and he’s now closing the gap.

The commentary in Craig’s mind told a different story. “When third and fourth place pulled up to me,” he said, “I forced myself to run with them even though I wanted to give up and I was discouraged.” He prayed for one more chance.

And there is 500 meters to go and Nick Rose is getting tired.

And Orthmann is coming on the charge and that is, Bobby, a tragedy for the man who has led so far. I can’t remember West Germany ever

winning this international race.

Nick Rose, who’s thrown down the gauntlet, cut out the pace, and Orthmann has closed on him and it’s a tremendous finishing pace.

And Virgin is closing, too.

This is a magnificent finish.

Craig had run through his fatigue and recovered. He tried to gather himself for one last surge. The race had become a lung-blasting version of poker in which none of the players knew what hand the others held. “I knew I had to answer what they put down and then I had to lay down a card of my own and hopefully it was going to be the joker or the ace card, and that’s how I played it,” Craig said.

Orthmann has got him in his sights. There is about 500 meters to go. Less than that, maybe 400 meters to go, and Orthmann is on his shoulder and Nick is looking tired.

Oh, what a tragedy.

And Orthmann, if he goes and continues to go, that will be the break point and Nick Rose has got to go with him. He must try and stay. Nick Rose, head rolling from side to side.

The crowd absolutely lined with supporters here.

Orthmann of West Germany with the finishing speed.

Oh, and it’s agony for Rose to watch this.

They’ve got about 250 meters to go and a gap is growing and Virgin is closing on Nick Rose.

What a tragedy for the Bristol Boy.

Orthmann going away.

Virgin closing.

Orthmann of West Germany. Nick Rose. Craig Virgin of America. The first three.

And there is not much between them now. This could be the closest title.

Orthmann’s attack on the last straightaway forced Craig to face a fourth and final “moment of truth.” Should he answer the surge now or wait? Like all of his decisions that day, this one was made in a split second. “I just knew from my practice run the day before that it was just a touch

too early and I let Orthmann do his thing,” said Craig, who forced all negativity out of his mind. “I held off Antipov and Schots. None of us went with Orthmann when he made his move.” Orthmann was no stranger to Craig, who’d lost to the West German in a 3K seven years earlier.

And Virgin is burning up and going past Nick Rose and closing on Orthmann with 100 meters to go.

Orthmann has been overtaken on the inside.

Craig Virgin of America goes into the lead and won’t be overtaken. It’s a unique American victory, I’m sure.

Nick Rose is third and it’s America one, West Germany two. Tragedy for Nick Rose of England.

The Double V

With 350 meters left, Orthmann, wearing a white cyclist’s cap, had lifted his stride and taken the lead, but he’d moved too soon. “Whether it’s sports, business or love, timing is everything,” Craig said. “I timed that last half lap better than anybody else.” As Orthmann glanced over his left shoulder, Craig passed on the right. He sprinted through the finish chute and lifted his hands to make a pair of peace signs. “It was not peace at all,” he noted. “It was Winston Churchill’s V for victory. I had two Vs, one for Virgin and one for victory, and that became my

signature salutation for many races to come.”

Craig called his kick that day one of the best of his career. His time was 37 minutes, 1.1 seconds, which was 1.2 seconds better than Orthmann and 4.7 ahead of Rose. Those closest star. He’d helped the United States place second, one of five runner-up efforts he’d be part of. Rose’s English squad won with 100 points, 63 ahead of the Americans. The race reminded Rose of the 1973 NCAA meet when he’d lost an 80-yard lead to Steve Prefontaine. “People will say if I’d started slower I’d have won,” Rose told Kenny Moore of Sports Illustrated, “but if I’d started slower it wouldn’t be me.” When contacted 29 years later, Rose maintained, “That’s the way I ran. I just went out there without intention. I felt good and took it on. It’s unfortunate it was a very, very long finishing straight. It seemed like, gosh, the end of a marathon. Craig hung back and his timing was spot on.”

In a 2003 book, The Toughest Race in the World—a Look at 30 Years of the IAAF World Cross Country Championships, the account of the 1980 race notes Rose admitted “that he had lost count of the laps and thought there was only one lap remaining when in fact there were

two.” The same claim was made by Rose’s former Western Kentucky University teammate, Swag Hartel, who said, “He got to the end of the fourth lap and he found out he had to go another lap. Nick is not the kind of guy to make excuses, but he thought he had the race won.” When contacted in 2010, Rose insisted he hadn’t miscounted. “I knew how many laps it was,” he said. “I can’t take anything away from Craig. He’s a worthy champion and he won the race on the day and well done to him.”

The bottom line was a 24-year-old farm boy from tiny Lebanon, Illinois, had proven American distance runners could beat the best in the world. History, however, has shown all he really proved was that he could. Through 2016, no other American man had become World Cross Country champion. To this day, while working as a professional speaker, Craig shows the video of that 1980 race. Each time, his sprint finish causes the audience to erupt in applause as if the race had just finished. “There are moments of truth in every race,” he tells them. “I had

several in that race where, thank God, I made the right decision rather than giving in to discouragement and frustration.”

Medical Detectives

Craig’s victory in Paris cemented his position on the world stage. World-class athletes are thought to be perfect physical specimens. Yet, as previously noted, Craig was far from perfect when he came into the world on August 2, 1955. He was born with a congenitally enlarged ureter known as a megaloureter. The condition allowed urine to flush back into his kidneys, causing frequent infections. His condition was fairly rare. Out of every 500 births, one child has some congenital anomaly of the kidney and urinary tract. A doctor in 1982 described the appearance of Craig’s kidneys as “very bizarre, but they have good function and he should be able to keep them.”

Fortunately for Craig, medical science helped manage his condition long enough for him to become a world-class runner. It took some savvy detective work by doctors in 1960 to figure out what was wrong when a five-year-old Craig awoke from a kindergarten class nap seriously ill. The doctors’ first guess was appendicitis. As Craig was prepared for an appendectomy, a doctor noticed blood in Craig’s urine. The surgery was canceled as he underwent more testing, which pointed to a urological problem. Reconstructive surgery was scheduled just before Valentine’s Day. His kindergarten classmates all sent valentines.

Within a year of that first surgery, it was clear it had failed to permanently stop the reflux and frequent kidney infections. Dr. Stuart Mauch was experienced, but he’d never seen a condition like Craig’s. To the Virgins’ shock, their family physician said that Craig’s kidneys were so damaged by all the infections, it was unlikely Craig would live past age 18. That information—or exaggeration as it would later be determined—would appear in feature stories about Craig his entire career. The news rightfully caused his parents tearful anguish. Saving the day was Dr. William Mellick, a urologist at Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital in St. Louis, who took over Craig’s case and kept him alive for eight years with a sulfonamide antibiotic known as Gantrisin, which battled bacteria in the kidneys.

Craig took half a pill in the morning and half at night until he needed to have a second reconstructive surgery at age 13. In the meantime he dealt with chronic infections. On a good day, he would feel a “low ember burn.” On a bad day, he’d have to be on the lookout for symptoms because he only had 24 to 48 hours to reach a hospital for intravenous antibiotic therapy before the burn turned “white hot.” Between the first surgery and the second seven years later, he was hospitalized half a dozen times.

The second surgery in 1968 involved a new technique for reattaching the ureter, the tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder. The technique involved “sewing” the ureter through the bladder wall. Craig was sent home from the hospital and for the next 60 days had a bladder drain tube coming out of his abdomen. The tube funneled urine into a bag attached to his leg, not exactly the preferred accessory for a self-conscious eighth-grader.

Eleven years later, Craig’s mother, Lorna Lee, told Amby Burfoot of Runner’s World that “the teachers let him go to the bathroom alone when no one else was there, and lectured the other kids on how to react.” The procedure restored 70 percent of the function to the damaged kidney. “He never really had to be sheltered,” his mother told the Belleville News-Democrat in 1973. Doctors told Craig’s family he was free to enjoy any activity except contact sports such as football.

Craig’s second surgery around Thanksgiving of 1968 meant he went from being a member of the Lebanon Grade School basketball team to temporarily being its manager, but that job got interrupted. “In the middle of a Christmas Tournament game, suddenly I had this urge [to urinate],” he remembered. “I said, ‘I’m not supposed to have this feeling.’ The tube was plugged up.” A doctor, without using anesthesia, replaced the tube with a new one. For the next month, Craig had to consume an inordinate amount of cranberry juice every day to regulate the

acidity of his urine. The second operation came eight months before he began his running career on August 3, 1969, a day after his 14th birthday.

Pain Tolerance

Repairing the male urinary tract circa 1960 to 1969 was problematic and painful. In Craig’s case, a trip to the hospital meant an intravenous pyelogram, or IVP, was in his near future. An IVP delivers dye so X-rays can be read. To receive an IVP meant you had to be catheterized. Craig used his mind to set aside the agony of painful procedures. Catheter pain was the worst. “When the infection would get out of control, I would only have a few hours before I was in a fever and then the shakes,” he said. “If it went far enough, nausea would come in.” As he said in Marc Bloom’s book, Run with the Champions, “The discomforts I suffered as a youngster taught me to disassociate from pain.”

It’s a prerequisite that distance runners listen to their bodies. If they don’t, a hot early pace can make for an agonizing finish. Likewise, a minor injury can turn into a major headache. By the time Craig’s running career began, he was adept at listening to his body or, when necessary, disengaging from it.

“After the second operation,” Craig recalled, “I thought things were under control and the problem would be all right.” That was wishful thinking. A stone was discovered in Craig’s right kidney in 1981 when he was 26. In August of 1983, the stone was removed. In 1994, his right kidney was removed, an event he blames—along with a 1997 auto accident—for short-circuiting what he hoped would be a successful age 40-and-over running career. One kidney couldn’t quickly filter all the lactic acid produced by running.

Craig’s surviving left kidney is more than three times the size of a normal kidney, giving him almost the same filtering capacity as those with two kidneys. He keeps an eye out for any symptoms of kidney trouble. As he said, “I now have no backup.” If he has symptoms, he visits a

urologist pronto. When he has annual blood tests, they check his creatine level, which could indicate a problem. Doctors don’t anticipate further issues, but he must be monitored for life.

Some parents whose children have medical histories such as Craig’s might have been leery about allowing them to participate in something as taxing as distance running. Craig’s were not. He seemed healthy after the second operation so there was no reason to be overly protective. Looking back, he appreciates being treated like a normal kid. Craig isn’t convinced perfect kidneys would have made him a better runner. He admits they may have better filtered lactic acid and other waste from his bloodstream and thus boosted his performance. “On the other hand,” he said, “had I not gone through that experience in my youth with infections and having to learn to monitor my body, and then having to learn to disassociate from the pain of medical procedures or the pain when I got really infected, would I have acquired the skills to run through the pain that I did later on in my athletic career? I don’t know.”

Meet the Parents

Craig’s father, Vernon, grew up south of Lebanon, Illinois. (Craig was raised on a farm a few miles north of Lebanon.) Vernon’s father, Charles Virgin, was a row crop and dairy farmer who also peddled eggs and garden vegetables. In 1915, the 21-year-old Charles married 19-year-old Grace Muck, who was born in the same farmhouse south of Lebanon where she’d die in 1972. Charles and Grace met at a dance back when it took a horse and buggy to get there.

Vernon would grow to match Charles’s work ethic and take it to another level. As a young man, Vernon channeled his intensity into farming. Beginning in the 1960s, he also ran a livestock equipment distributorship while Lorna Lee handled the bookkeeping. She also worked as a school teacher.

Vernon was the youngest of five children and Lorna Lee was the oldest of five sisters. She was born in northeast Indiana near Fort Wayne. Her parents, Dwight and Rachel Putt, moved to Lebanon during World War II so her father could teach at nearby Scott Air Force Base where all Army Air Corps radio operators trained. Rachel was a homemaker, as was Grace. Both grandmothers kept a tinful of cookies on the counter for their grandchildren.

Lorna Lee was “book smart,” graduating at age 19 from Washington University in St. Louis in just three years and one summer. If Craig got his intensity from “common-sense smart” Vernon, he got his knack for organizing disciplined training schedules from his mother. Both parents contributed to Craig’s slender build. In their wedding photo, “they look like two toothpicks,” according to Craig’s brother, Brent. The 21-year-old Vernon appears to weigh about 125 pounds and 19-year-old Lorna Lee less than 100.

A popular story in Virgin family lore is that Lorna Lee met Vernon in a Lebanon High School typing class. For a lesson on correct posture, students had to balance a coin on the back of their hands as their fingers touched the keys. Lorna Lee didn’t have any coins so Vernon

loaned her some, an act that would alter the fabric of American distance running forever.

Excerpt from Virgin Territory: The Story of Craig Virgin, America’s Renaissance Runner by Randy Sharer, the authorized biography of Craig Virgin. Used with permission. You can order a copy of the book, autographed by Virgin, here.

We’ve also released an excerpt from Chapter 17, which addresses Craig being a pro runner while pretending he wasn’t and the US boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow (Virgin won the 10,000 meters at the US Olympic Trials).