The Rise of Syracuse: How a Cross Country Powerhouse Was Built From Scratch in 10 Years

In 2005, Syracuse was a middling Big East team over 30 years removed from its last NCAA championship appearance. Now it’s one of the premier cross country programs in the nation. How did it happen?

By Jonathan Gault

Published September 15, 2017

On Saturday, November 21, 2015, Griff Graves, Syracuse University Class of 2012, was sitting with his wife Cassie in Zazzy’z Coffee House and Roastery in Abingdon, Va. At 12:54 p.m., he pulled out his iPhone, scrolled through his contacts and composed a text to 10 of his fellow Syracuse cross country alums.

291 miles northwest of Zazzy’z, at E.P. “Tom” Sawyer State Park in Louisville, Ky., the start of the men’s race at the NCAA Division I Cross Country Championships was six minutes away. Syracuse entered the race ranked No. 2 in the country, searching for its first national title since 1951, but No. 1 Colorado was heavily favored to win its third straight championship.

For the next 45 minutes, as Graves and his former teammates watched the race unfold online, they texted each other updates, words of encouragement, anything to remind each other that they weren’t riding this emotional rollercoaster alone. Rob Molke ’14 and Pat Dupont ’12 watched together in Molke’s second-floor apartment in East Harlem, N.Y. Graves yelled at his computer in Zazzy’z, drawing strange looks from the half-dozen other customers in the room. Joe Whelan ’14 watched it from Lake Dallas, Tex., with his roommate’s pit bull, Cooper, the dog growing more and more excited with every one of Whelan’s cheers.

With two kilometers to go, Syracuse and Colorado were tied at 99 points apiece. Even once the race was over, it was impossible to tell who had won. The SUXC alums waited desperately for the final scores. After a few minutes, it was official:

1. SYRACUSE 82

2. COLORADO 91

And then the text messages began flying:

Joe Whelan: I’ve paid my dues / Time after time / I’ve done my sentence / But committed no crime …

Rob Molke: OMG this is why we went there so proud

Steve Murdock (Class of 2011): I’ve never been more happy about anything

Forrest Misenti (Class of 2013): Who isn’t in tears?!

Rob Molke: WHO IS DRIVING TO CUSE TODAY/tomorrow???

Steve Murdock: Remember when everyone questioned why we went to Syracuse?

Griff Graves: Yep

Steve Murdock: THIS IS WHY!!

Forrest Misenti: This is the best day of my running career and I didn’t even run.

Andrew Palmer (Class of 2015): Dude…this one is a big middle finger to everyone who called us stupid for trying for the podium after we had never been top 10, of for trying for top 10 when we had never made NCAA. There is something more to the sport than just science. These [young] dudes had a bunch of us old guys crying…incredible what you can accomplish if you believe in the guy telling you how to do it

***

Step 1: Developing a Brand

Walk into Chris Fox’s office and the first thing you notice are the trophies. Front and center are three massive ACC Championship trophies, with a replica of the 2015 NCAA trophy in the middle. The Orange have piled up so many trophies since Fox, a round-faced 58-year-old West Virginia native, took over as head coach of the Syracuse men’s and women’s cross country and track and field teams in 2005 that he has run out of room, the haul spilling over from the windowsill to the cabinets and radiators in front. The first conference trophy Fox worked so hard for is an afterthought, obscured by the more recent ones. Fox can’t even recall what year it is from.

“Coach Bell! What year did we win our first Big East?”

“2009.”

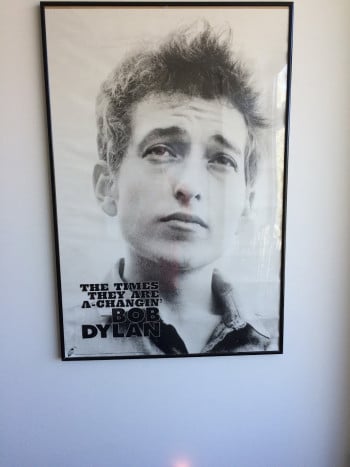

But to learn the full story about where those trophies came from, you need to divert your gaze to the left. Back in 2005, when that windowsill was empty, Fox hung a black and white print of Bob Dylan. At the time, he thought the words in the bottom left corner, printed in bold black type, seemed appropriate: “The Times They Are a-Changin’”

When Daryl Gross took over as Syracuse athletic director in December 2004, he inherited a men’s cross country program synonymous with mediocrity. The Orange has never finished higher than third in the Big East since joining the conference in 1979; their average finish was 7.7. Syracuse hadn’t qualified for NCAAs in more than 30 years (since 1974, when they finished dead last), and hadn’t finished in the top 10 at nationals since 1959. Yet when Gross set out to hire a new head track & field/XC coach prior to the 2005 season, he did so with the intention of focusing on cross country first.

“We weren’t going to be the hotbed of sprinters or any kind of specialties like that,” Gross said. “Those are going to be in the Sun Belt area, California, Texas, Florida. You know, the usual places where you may have a plethora of sprinters and 400-meter runners and those type of things. I really thought if we had a distance emphasis at Syracuse, given where we were located, that that may play to our advantage for not just cross country but track and field as well.”

At the time, Fox was coaching cross country at his alma mater, Auburn, and when he interviewed for the Syracuse job, Gross was impressed by Fox’s lengthy professional career, which included personal bests of 13:21 (5k) and 27:53 (10k), five Olympic Trials appearances and a World Championship team (1995). Gross saw some similarities between Fox and another successful coach he had a hand in hiring during his time at the University of Southern California.

“When I brought Pete Carroll into USC [to coach the football team], he had some of the same characteristics as Chris Fox,” Gross said. “Both are very comfortable in their own skin. …They do such a great job of teaching and he’s that guy. He’s got the special stuff, the it factor, the je ne sais quoi.”

Gross’ opinion of Fox only grew as he began working with him on a day-to-day basis, and he started winning fans across the athletic department, including a certain men’s basketball coach.

“Jim Boeheim has so much respect for Chris Fox and what he’s done and he calls him the best coach in the department,” Gross said.

Gross’s mandate of focusing on cross country first was music to Fox’s ears.

“I got to do what almost any distance coach in this country would like to do: have control of the scholarships and be told I want a great cross country program before I want anything else by the AD,” Fox said. “We were given a really nice gift and it was up to us. Didn’t have any limitations put on us.”

Fox had the perfect lieutenant in Brien Bell, now the team’s associate head coach, who has been with Fox at Syracuse since day one. Bell, 40, is a man obsessed with the process, motivated not by winning but a hatred of losing. He loves solving the problems of how to construct a roster (his dream job is general manager of the Toronto Blue Jays) and lives for the minutiae of running a program, whether it’s figuring out how to allocate scholarship money, which recruits to go after or how to motivate an athlete. Building a program from scratch at Syracuse was an ideal challenge.

Armed with a solid budget, Gross’ support, and advice from his coaching mentors — particularly Martin Smith, who won a pair of national titles at Wisconsin in the 1980s — Fox set about constructing his team, and from day one he told anyone who would listen — recruits, parents, coaches — that his goal was to win a national title.

“I don’t know that we ever thought we would really win a national championship, but we were going to coach like that, we were going to recruit like that, we were going to evolve that,” Fox said. “We got made fun of a lot early on. We used to keep a list on these whiteboards of coaches that we really love and respect that told us, It can’t be done there. You cannot do it at Syracuse. You’re going up against Nova, you’re going up against Georgetown, you’re going up against Providence. You’re going up against the East Coast establishment with a program that’s never done it.”

And that was just in the Northeast. Nationally, it was even harder to break through. From 1973 through 2014, the 42 national titles awarded in men’s cross country were split between just eight schools – none of them east of Wisconsin. There wasn’t any room at the table for an outsider like Syracuse.

The program’s lack of recent success was not the only thing working against it. Syracuse, located in Central New York, isn’t close to anything — four hours from New York City, five hours from Boston, five and a half hours from Pittsburgh. Even Buffalo is two hours, twenty minutes down I-90. Then there are the winters. From 2001 to 2015, Syracuse averaged 130 inches of snow per year. In 2014 the Weather Channel proclaimed it America’s Snowiest Major City. Not exactly ideal training conditions.

To counteract that and Syracuse’s expensive private school tuition, Fox had to sweeten the pot. So, with Gross’ blessing, he began offering big scholarships, handing out full rides to kids who weren’t good enough to get them from other schools.

“We had to make it enticing for them,” Fox said. “I wouldn’t say we overpaid. We paid what we needed to pay at the time to get legitimate.”

Bell began canvassing the country for recruits. Most of the top guys ignored him. But not all. Fox and Bell landed a Foot Locker finalist, Jay Koloseus from Connecticut (20th at FL), in their first recruiting class. The next year, they brought in Steve Murdock, a New Yorker who finished third at Foot Locker as a senior and won the individual title at Nike Team Nationals (now known as Nike Cross Nationals). In 2008, they hit mother lode, securing commitments from four Foot Locker finalists from three different regions — Tito Medrano from the Midwest (30th), Griff Graves from the South (33rd) and Pat Dupont (17th) and Zach Rivers (28th) from the Northeast.

All four had significant financial incentive to come to Syracuse, but more than anything it was the coaches’ message that resonated with them. Graves, whose father roomed with Fox in college at Auburn, had become friends with Murdock at Foot Locker in 2006 and was the first to commit from the Class of 2008. When he got to San Diego for the 2007 Foot Locker meet, he put the sell job on his future teammates.

“I talked to them and I was like, Hey guys, if we all went together, how cool would that be? Help try to build a program that’s already on the rise but nobody knows they’re on the rise yet,” Graves said.

It was the same pitch Fox and Bell were giving to every recruit, and it worked.

“This idea of having a team that had been unranked and was building and becoming something special, that was more intriguing to us than anything else,” Medrano said.

It’s impossible for coaches to get a full sense of a kid’s mental makeup, but Fox and Bell’s shoot-for-the-stars pitch and Syracuse’s natural environment wound up self-selecting tough-nosed kids with self-belief levels as high as the Syracuse snow banks. The guys that wound up coming relished training in the winter; to them, it was just more proof that they were tougher than anyone else in the country.

“I think that mentality also had a big part in why Syracuse had so much success,” alum Rob Molke said. “Everybody there is pretty mentally tough when it comes to training…I thought we were very well-prepared for any challenges that faced us based upon the weather conditions and the snow and just going into it knowing that it was sometimes going to be a challenge in the winter months to train made us a little bit better I think.”

Ironically, Bell has done studies that show only about 40 percent of Foot Locker finalists end up running at the NCAA cross country championships. But a Foot Locker guy’s value, especially before the rise of NXN, wasn’t just about what the athlete could contribute on the course — it was a sign of legitimacy. Recruits started noticing the guys Fox and Bell were pulling in.

“Every year it’s going up a little bit,” Fox said. “9:15 [high school two-milers] became 9:10, 9:10 became 9:05.”

As the program began to find success — Syracuse and Colorado are the only schools in the country to have finished in the top 15 at NCAAs every year since 2009 — those top-tier guys who once ignored Bell started responding. And thanks to the athletic department’s dollars, the school had the resources to fly Bell and other assistants all over the country for home visits.

Justyn Knight‘s recruitment showed just how far the program had come. Almost every school in the country wanted Knight, who ran personal bests of 8:07 (3k) and 14:08 (5k) as a high schooler in Canada. Knight, who liked Syracuse because of how Fox had developed talent, wanted to come, but internally, Fox wasn’t sure what to do. From the beginning, his goal was to build the program with American talent.

“That just goes back to my own running,” Fox said. “[When I was in college], there were American teams and then there was UTEP, or before that Washington State. Or some teams that had a bunch of English guys like Providence. I think there was an establishment at one time and Coach [Mark] Wetmore still does it [at Colorado]. And he stands hard on it and I appreciate what he has to say about it. Whatever your justification is, it’s just something we wanted to do. I’m an American runner, so I wanted to help American running.

“We contemplated a long time, should we get Justyn? First of all, can we get Justyn and then should we do that? We’ve always sort of spouted out, hey we’re going to be the great American program, we’re going to do it with regular guys and we’ve always said that. And then you get a chance to get a kid who ran 8:08 (for 3k) in high school. I called my mentors, two or three of them, and they said you’ve gotta do it. Obviously, Justyn’s a special case…not only is he an incredible runner, he’s an incredible person.”

Though Knight is technically a foreigner, his hometown of Vaughan, Ontario, is just over a four-hour drive from Syracuse’s campus — the same time it would take to drive from Syracuse to New York City. Now a senior, Knight is indisputably the greatest runner in Syracuse’s history and was the top runner on their 2015 title team. He enters 2017 as the top returner from last year’s NCAA meet (second overall) and last month placed ninth in the 5,000-meter final at the World Championships in London.

And, just as Foot Locker finalists begat Foot Locker finalists, other foreign-born athletes noticed the success Knight — and by extension, the program — enjoyed under Fox and wanted to be a part of it. In 2015, another Canadian, 3:38 1500 runner Adam Palamar, transferred to Syracuse from the University of Tulsa. The next year, Iliass Aouani, an Italian who had run 13:55 at Lamar University, followed suit.

“It’s happened more with success,” said Fox, who has an adopted son who was born in Ethiopia. “We didn’t go out looking for Iliass, he found us. And again, brought him in for a visit, super guy, super credentials. It all fit. Do I go to Italy or Kenya looking for people? No. If somebody fell in my lap like Iliass did, I’d probably take him as long as we like him. This will be an American program first but it won’t be an American-only program.”

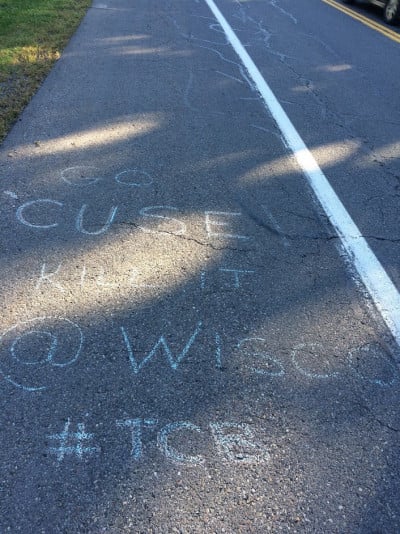

The Orange have made so many breakthroughs under Fox that it’s impossible to pinpoint one moment that definitively turned around the program. The 2009 season was big, for sure, with Medrano, Graves and Dupont leading the way. Syracuse won the inaugural Wisconsin Invitational, defeating Georgetown for the first time. Four weeks later, the Orange beat Georgetown again to earn the program’s first-ever Big East title. Syracuse ended the year by snapping a 34-year NCAA drought and finishing 14th at nationals.

That level of success became a baseline expectation for the program — since then they’ve won their conference every year except for 2011 and made NCAAs every single year — until another breakthrough in 2014, when Syracuse won the Wisconsin Invitational (by this point, a much stronger meet) once again and finished just outside the podium at NCAAs in 5th (after having finished 10th, 15th, 15th, 14th and 14th the previous five years). Since then, Fox’s goal has been to contend for a podium spot every year.

Fox was helped along the way by the control Gross gave him over scholarships. Only five guys score on a cross country team, and though Fox said that he doesn’t use all 12.6 track and field/XC scholarships on distance runners (ace hurdles coach Dave Hegland gets a couple as well), the bulk of the money goes to distance runners. The athletic department’s growing revenue (a good chunk of which stemmed from Syracuse’s lucrative leap to the ACC in 2013) also proved to be a rising tide that lifted all boats. Gross said the athletic department budget grew from around $48 million in 2005 to $85 million 10 years later.

“My philosophy wasn’t to just to distribute revenues to the sports that we thought were the most important,” said Gross, who stepped down as Syracuse AD in 2015. “My thing was for everyone to have revenues across the board because we thought we could win in everything at Syracuse. So we took the revenues and got folks better operational budgets and we were off and running.”

Indeed, a day after the men’s cross country team won the NCAA title in Louisville, the women’s field hockey team accomplished the same feat in Ann Arbor, Mich. Two weeks after that, the men’s soccer team booked its ticket to the final four. Like the cross country squad, neither program had a track record of national success before Gross arrived.

That said, it wasn’t easy building a winner in Syracuse, New York. Syracuse doesn’t have the Nike money of Oregon, the altitude of Colorado or the perfect weather and academics of Stanford, but it’s creating something more important: an identity. And while the heroes of the 2015 title team — Knight, Colin Bennie, Martin Hehir — had a lot to do with forging that identity, there’s a good chance they’re not on campus without guys like Dupont, Medrano, Graves and Forrest Misenti blazing the trail and showing it was possible to win at Syracuse.

“We didn’t slap this thing together, we built [it],” Fox said. “Each group brought us to another level.”

***

Step 2: Shaping the Culture

Chris Fox and Brien Bell met sometime in the early 2000s, at a meet somewhere, though when you’ve been in the coaching business this long, they have a tendency to run together. Fox was coaching at Auburn while Bell was an assistant at his alma mater, La Salle, under the late Charles Torpey, one of Fox’s mentors during his career. Fox and Bell quickly hit it off, bonding over a shared interest in cycling and the outdoors, and when Bell told Fox he was planning a camping vacation in the South with his wife during the summer of 2005, Fox invited the Bells to stay at his house. The day before Bell arrived, Gross called Fox to ask if he was interested in the Syracuse job. Fox knew just the man to bring along as his assistant.

“I asked [Bell], ‘Do you want to go if I go?’ and he said, ‘Yep,'” Fox said.

Now the two men are in year 13 together in Syracuse. Their relationship is classic good cop, bad cop. Fox is laid back, always there to offer an ear or a pat on the back after a bad workout. Most practices begin with Fox asking members of the team for fun facts. Did you know that female kangaroos have three sex organs? (Thanks, Aidan Tooker). Or that Red Sox outfielder Mookie Betts has bowled two perfect games? (Hat tip, Philo Germano). Fox rarely yells, but when he gets serious you better pay attention because what he says is going to be important.

Serious is Bell’s default setting. It’s his job to lay down the law and preserve the culture he and Fox have worked so hard to develop. Late for practice? Bell will take you aside and chew you out. Not taking the sport seriously enough? Bell will let you know about it.

Germano, now a senior, redshirted his freshman fall, so his first meet in a Syracuse singlet came at Penn State in January 2014, where he ran a disappointing time of 14:56. Germano was not happy, and the first person he saw as he stepped off the track was Bell, who felt similarly and let him know all about it.

“He was like, What have you been doing, did you even train? Had I been drinking or living a bad lifestyle?” Germano said. “Hearing his passion for it at that time, obviously I never want to do bad in a race, but hearing him and how much he wanted us all to do well, even if it was the first meet of the year, that’s when it started being like, all right, I’ve gotta be able to bring it every day, no matter what it is.”

The bespectacled Bell, perpetually sporting a Syracuse cap slung low over his head, operates on the principle of gravitation towards the mean: the belief that human behavior, especially in large groups, is attracted to the average. Normally, this gravitational force is driven by peer pressure. On a campus like Syracuse’s — ranked the No. 1 party school in the country in 2014 by the Princeton Review — that means late nights, drinking, anything considered part of the “average college experience.” Average is the monster Bell must battle every time a new class of freshmen arrives.

“The reason why everyone is acting very much the same is because it’s average,” said Bell, a teetotaler himself. “They want to fit in. There’s nothing average about excellence…The gravitation towards the mean, I am completely paranoid of that. If you let the 20th guy off the hook, he reaches up and gets the 19th guy. He reaches up and gets the 18th guy. You might say, oh, I don’t care, three guys at the bottom don’t care. Then before you know it, half the team is being slackers. So where do you draw the line? Well, let’s just draw the line at 20.”

So every year, Bell would get on the young guys. And every year, it would take them a little less time to get it. And as the team became more professional and more successful, peer pressure began to work in his favor.

“Now the peer pressure, other guys get pissed when you don’t do what you should be doing,” Bell said. “Because then it’s selfish because it effectively hurts the team and that’s in everyone’s purview now. They understand that.”

Bell’s approach works because his athletes, like Germano, see his passion for the sport, how hard he works for them. They see him on the corner of Barry Park every day, ready to join in the morning double. They see him take any slight in the media, any shot at program on Twitter, as a personal affront. More than anything, they see that whatever Bell may have yelled at them for in the past, it was done out of love, out of a desire to see each athlete realize his full potential.

“They care about you and when you know that, not just think that that’s true, but when you know that that’s true, it leads to a great relationship,” said Joe Kush, the seventh man on the 2015 title team.

Fox and Bell also come to practice every day with chips on their shoulder the size of Texas. For Fox, that mentality began in high school, where he stood 4’11” as a junior — “I still think that I’m short,” said Fox, who is now up to 6’1″. Anyone who said Syracuse was too snowy to develop distance runners, that they’d never challenge the blue bloods like Colorado and Oregon simply added fuel to the fire.

“We always had a sense of ‘The world doesn’t want Syracuse to be good,'” said Dupont. “I think there was just a lot of things that we felt like the cards were stacked against us and it motivated us to say we could perform through that stuff, we’re gonna prove the world wrong and say Syracuse is a place where you can be good.”

Even now, with a national title in their back pockets, Fox and Bell don’t have to work hard to find motivation.

“I think that those two guys could win 10 national championships in a row and show up to practice the 11th year and find something to be pissed off about,” said 2015 alum Andrew Palmer.

***

Elvis Presley wore a belt buckle while performing with the letters “TCB.” It stood for taking care of business, and it’s a mantra Fox adopted for the program, the letters now splattered all over Syracuse’s gear or, in the case of former SU runner Shawn Wilson ’18, on his upper right arm in the form of a tattoo.

Taking care of business began by nailing down the basics. Get to bed early. Cut down on drinking and partying during the season. Double in the morning. Once that sort of behavior became the norm, Fox and Bell began looking for other edges to exploit. Now they have athletes test their blood to monitor hemoglobin, hematocrit and ferritin levels. They add more iron to their athletes’ diets late in the season.

“In the last four years, our recruiting thing has kind of changed,” Fox said. “The way we approach everything [is], you want to be a professional runner? This is the step. We want to do things –outside of we’ve got to go to school, make good grades — like this is Jerry Schumacher‘s group. If you come here, you want to be a pro.”

No athlete embodied the Syracuse ethos more than Marty Hehir, a guy whom Fox believes “changed the way kids on the team approached the sport.” A 9:00 high school 3200-meter runner from Washingtonville, N.Y., Hehir was Syracuse’s top runner from his first season in 2012 (he redshirted in 2011). Hehir wasn’t a vocal leader, but he was friends with everyone on the team and had 100 percent faith in his coaches. He came to practice every day, did exactly what Fox told him and continued to improve.

“I think the biggest step the program took was when Martin Hehir showed up on campus,” Medrano said. “He was a freshman and when I was a fifth year and I could tell right away that he was going to be a talent but not just a talent; he was going to be a really good leader.”

As Hehir grew into that role as an upperclassmen, the younger guys took notice of his professionalism and unshakeable devotion to the coaching staff, none more than Justyn Knight, who frequently roomed with Hehir on the road. Incredibly talented but naïve as a freshman, Knight had a habit of becoming nervous before big races. It fell to Hehir to calm him down. Having gained his trust, Knight peppered Hehir with all sorts of questions — when to go to bed, when to double in the morning, when to make his move in a race. Knight’s pre-race routine is now modeled on modeled on Hehir’s: he shakes out at the same time and always eats the same meal (oatmeal) three hours before the race. If not for Knight, Hehir, who graduated in 2015 with PRs of 13:35 (5k) and 28:27 (10k) and two individual conference titles in cross country, would be the greatest runner in Syracuse history. So perhaps it’s fitting that Hehir, a team guy until the end, mentored the man who has eclipsed him as the program’s brightest star.

“Martin was my hero and he still is to this day,” Knight said of Hehir, now a runner for the professional HOKA ONE ONE Northern Arizona Elite team.

***

Step 3: Building a Champion

Head east from the Syracuse campus along East Colvin Street, hang a right onto Jamesville Road, then a left onto Route 173 past the Jamesville Fire Department and you’ll arrive at the six-and-a-half mile stretch of Sweet Road that has molded the current generation of Syracuse runners into champions. The route climbs almost 900 feet, uphill the entire way, as it passes farmhouses, foliage and wide-open fields from the 173 intersection to the finish in front of Immaculate Conception Church. It’s the site of Syracuse’s workout today, a glorious early fall Friday in October 2016, a week before the Orange travel to Madison to go after their third consecutive title at the Wisconsin Invitational.

Sweet Road is the foundation of Fox’s coaching philosophy built on strength training and moderation. Today it’s one more step on a path that he hopes will lead to another national championship. Knight, dressed in a blue Syracuse tee tucked into Team Canada shorts, and Bennie, who, as always, sports a gray sleeveless tee with two bikini-clad women flanking a panda (don’t worry about it), comprise the top group for today’s session; they start 45 seconds behind the large second group. The large eight-foot shoulder on the road gives them plenty of space to navigate the occasional passing car.

Knight and Bennie are instructed to hold back early, and they pass one mile in 5:26, in control but still pretty quick for the uphill course (5:12 is the fastest anyone’s ever come through, and that was with a tailwind). As they climb past the rural houses, Knight is barely breaking a sweat despite the 77-degree heat. Halfway through, Fox, following along in a van, can sense his star pupil growing restless.

“Go get ’em,” he says, giving Knight the green light to reel in his teammates up ahead.

For all the work Fox and Bell have done to build the program, for all the guys they’ve coached up, they don’t win a national title without a superstar. On a cross country team, the most important guy varies, but the most valuable guy is always the same: the #1 runner. In a sport where every finisher is assigned a numerical value, that’s just basic math. Knight, who ran 3:39 (1500) and 13:34 (5k) as a freshman, was a superstar from day one at Syracuse. When you’ve got a guy that good, the first priority is simple: Don’t screw him up. And Fox hasn’t, managing his miles carefully, from 35 per week his freshman fall to 45 as a sophomore to 60 as a junior in 2016.

By four miles, Knight has erased the 45-second deficit and is working on putting a gap of his own on the rest of the squad. He keeps climbing, up “Heartbreak” at mile 5, where Pat Dupont used to lay the wood on guys during the early days. Knight is totally alone by the time he finishes at the church, but there’s no talk of course records as he grabs a drink from the back of the van and pulls up his bright orange basketball shorts for the cooldown. After briefly discussing the workout, Fox inquires playfully about Knight’s love life, a popular topic of discussion at practice the last couple days. He doesn’t know, or care, what Knight’s final time was. All that matters is the effort, and Fox knows that was good.

There’s no faking your way through this workout. If you’re weak, or if you’re carrying a few extra pounds, it will show on Sweet Road, the ultimate proving ground for an athlete’s power-to-weight ratio. Bell likens the uphill running to training at altitude.

“You’re able to get an aerobic stress on your system without tearing up your legs,” Bell said. “If we went to a track and tried to mimic the sustained heart rate and stuff we were getting, it would take days to recover.”

Sweet Road has been part of the program for years, but it took on an added significance after a disastrous performance at the ACC indoor meet at Clemson in 2014, where Syracuse took 12th out of 13 teams. After the meet, Fox and Bell gathered their charges and laid into them.

“We’re getting ready for cross next year, we don’t care about anything else,” Bell told them. “You guys are running [Sweet Road] the whole month of March, we don’t care.”

Every week, the team would pile into the vans and run up Sweet Road. As the snowbanks melted and the temperature rose, something interesting happened. Everyone started running faster. Joel Hubbard ran 3:43 for 1500, slicing seven seconds off his PR. Max Straneva went from 14:20 to 14:00 for 5,000. Reed Kamyszek went from 29:45 for 10,000 to 29:08. Fox noticed the trend.

“You run Sweet Road, you get better every time out,” Fox said. “It’s made my coaching a lot simpler. What do we do? Oh, let’s just go to Sweet Road. If you’re deciding, should we go to the track, six 800’s in 2:04 or…eh, let’s just go to Sweet Road because we know we get better. We’ve had guys break 4:00 off it, we’ve had incredible cross country seasons off it.”

The most famous of those seasons was 2015, and it’s fitting that the championship dream started to become reality on Sweet Road. By that point, the Orange had assembled a stellar top three in Knight, Hehir and Bennie, but there were questions about whether the team had the depth to go toe-to-toe with Colorado at NCAAs. The week before ACCs, the team ran a four-mile tempo up Sweet Road, took a short break and then ran a hard mile. Knight, Bennie and Hehir all broke 4:30. So did Germano. Usually breaking 4:40 for that mile (which, remember, is still uphill) is a sign you’re ready to be an All-American. Until then, no one had thought about Germano, who was 89th at Wisconsin, the team’s sixth man, as being at that level. A month later, Germano gained 14 spots over the final 2k to finish as Syracuse’s fourth man at NCAAs, 39th overall and an All-American. Syracuse won the meet by just nine points.

“[That was] the workout last year that where everyone collectively realized we have a shot to really win this thing,” Hehir said.

These days, it’s rare for Syracuse to go longer than 12 days without visiting Sweet Road during the cross country season. Any more than that and everyone starts to get anxious.

***

The crazy dream Fox and Bell shared when they arrived in 2005 is now a reality. Those trophies look nice in his office, but Fox hasn’t just built a winner; he’s built a legacy, linking scores of Syracuse runners through a shared pursuit of excellence. When Syracuse won NCAAs, the guys on the course in Louisville weren’t the only ones who felt like champions. Every alum who bought in back when that dream seemed a million miles away could take pride in helping to build something that lasted.

“It felt like you were still part of that program,” said Medrano, who was at the race and recalled embracing a teary-eyed Bell after the results became official. “It was something that Coach Bell had promised and Coach Fox had promised for so many years when they showed up. It was really, really cool.”

Who could have seen this coming when Fox took over in 2005? Well, Fox hasn’t changed offices since he took the job, and that Bob Dylan print still hangs to the right of his desk. The words to that song, wishful thinking a decade ago, now read like an eerily prescient prediction:

Come writers and critics

Who prophesize with your pen

And keep your eyes wide

The chance won’t come again

And don’t speak too soon

For the wheel’s still in spin

And there’s no telling who that it’s naming

For the loser now will be later to win

Cause the times they are a-changing

Full disclosure: The author is a graduate of Syracuse’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications.

More: Be a fan and talk about Syracuse and NCAA Xc on our messageboard:

MB: Syracuse – From Nothing to National Champ – How a Cross Country Powerhouse Was Built From Scratch in 10 Years

MB: Official 2017 NCAA XC Preview Discussion Thread –

Check out our NCAA XC Pre-Season Top 10 Rankings:

Men’s previews: #10 Oklahoma State & #9 Iona * #8 Oregon & #7 Wisconsin * #6 Colorado & #5 Stanford * #4 BYU & #3 Arkansas *#2 Syracuse & #1 Northern Arizona

Women’s previews: #10 Providence & #9 Arkansas * #8 Penn State & #7 San Francisco * #6 NC State & #5 Michigan * #4 Oregon & #3 Stanford *#2 New Mexico & #1 Colorado