I Was Bored, So I Watched the 1993 World Championship 5,000

Throwback Thursday #17

By Jonathan Gault

August 6, 2020

Welcome back to Throwback Thursday. With limited live events during the coronavirus quarantine, I’m plumbing the depths of YouTube and watching/sharing my thoughts about one classic race per week. If you missed any of the first 16 installments, click here.

Before I begin this week’s installment, a PSA: this may be the last Throwback Thursday for awhile. I started this series out of boredom stemming from a lack of live sports, but if the upcoming Diamond League meets in Monaco, Stockholm, Lausanne, Brussels, Rome, and Doha go ahead as scheduled, that won’t be much of a problem over the next couple months. To all of you who’ve reached out about the series and offered suggestions: thank you. Hopefully I can continue to entertain you by writing about new meets in the future.

And with that, it’s time to introduce this week’s race: the 1993 World Championship men’s 5,000-meter final. Quite simply, it is one of the greatest races in the history of distance running.

Even without context, it’s a stunning watch — Ismael Kirui drops a 60.21 sixth lap to break the race open and (spoiler alert!) holds on to win over the legendary Haile Gebrselassie. But the backstory make it even better.

First, you’ve got the classic distance running rivalry: Kenya vs. Ethiopia, personified by Kirui and the great Gebrselassie. They had first clashed in the junior race at World XC in 1991, Kirui taking 7th place, four seconds up on Gebrselassie in 8th. They raced again in the junior race at World XC in ’92, with Kirui taking the gold and Geb the silver in Boston. Their third clash, in the 1992 World Junior 5,000m final, was their best yet, with Geb beating Kirui to gold by just .05 of a second (some guy named Hicham El Guerrouj finished a distant third). The 1993 Worlds represented the first senior global champs on the track for both Geb and Kirui, a rivalry that had the potential to define the ’90s.

But while Kirui had a rivalry with Gebrselassie, the man he most wanted to beat may have been Morocco’s Khalid Skah. At the Olympics one year earlier, Skah had won a controversial gold in the 10,000 meters when a lapped Moroccan runner, Hammou Boutayeb repeatedly blocked Kenya’s Richard Chelimo after Chelimo and Skah had broken away from the rest of the field. Skah ultimately outkicked Chelimo for the gold. How does Kirui fit into all of this? Chelimo was Kirui’s brother.

With that in mind, let’s head back to Stuttgart, Germany, on August 16, 1993, for a World Championship final for the ages…

0:00 Geb looks young. Officially, he was 20 years old at the time of this race.

1:21 Kenya’s Michael Chesire wastes no time and rips a 61.32 first lap. 1976 Olympic 1500 champ John Walker, handling color commentary duties, sets the scene.

“The Kenyans will run as a team, they’ll try and protect [’92 Olympic silver medalist Paul] Bitok, because they feel he’s the best. Kirui feels his best chance is to run from the front.”

Also: I miss track & field in big stadiums.

1:42 Chesire is already opening a gap up front, and the top guys — Skah, Bitok, Geb, and Kirui (#785 on the outside) — have made their way to the front of the chase pack. Play-by-play man Bruce McAvaney calls Skah the favorite and Bitok “maybe equal favorite.”

2:21 Just look at that graphic! “Lap Time 58.92 … 800m 2:00.24.” Need I say more?

2:27 While this kind of early move seems crazy, McAvaney points out that the Kenyans had actually found success with it in major championships leading up to Stuttgart 1993.

“It’s a bit like [Yobes] Ondieki did when he did a 4:00 mile after the first lap and a bit in Tokyo,” McAvaney says, referring to the 1991 World Championship 5,000 final.

Ondieki held on to win that race. And in the 1988 Olympics, John Ngugi dropped a 1:58 800 early in race, broke everyone, and held on for the gold.

The difference here: Chesire was regarded as the weakest of the three Kenyans and not on the level of Ondieki or Ngugi, suggesting team tactics were afoot.

3:23 Chesire slows slightly up front as the gap shrinks between him and the chase pack. Walker, proving prescient, again emphasizes that Kirui will be enjoying the quick early pace: “Kirui knows only one way to run, and that’s fast from the front.”

3:36 McAvaney: “It’s obvious what the Kenyans have done here. They’re working for Bitok, who was second in the Olympic Games last year. They’re trying to set it up for Bitok to beat Skah.” Umm…not quite.

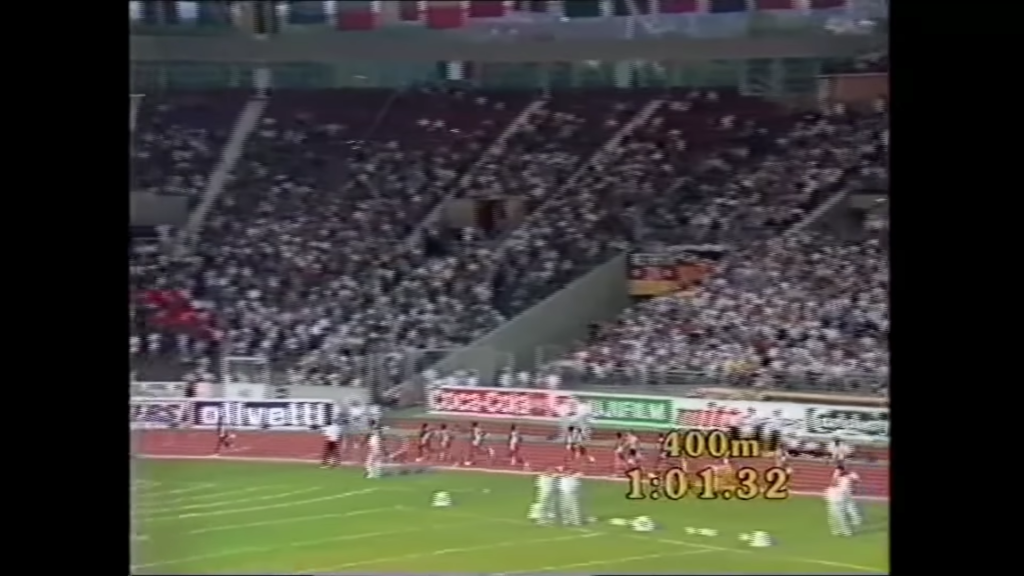

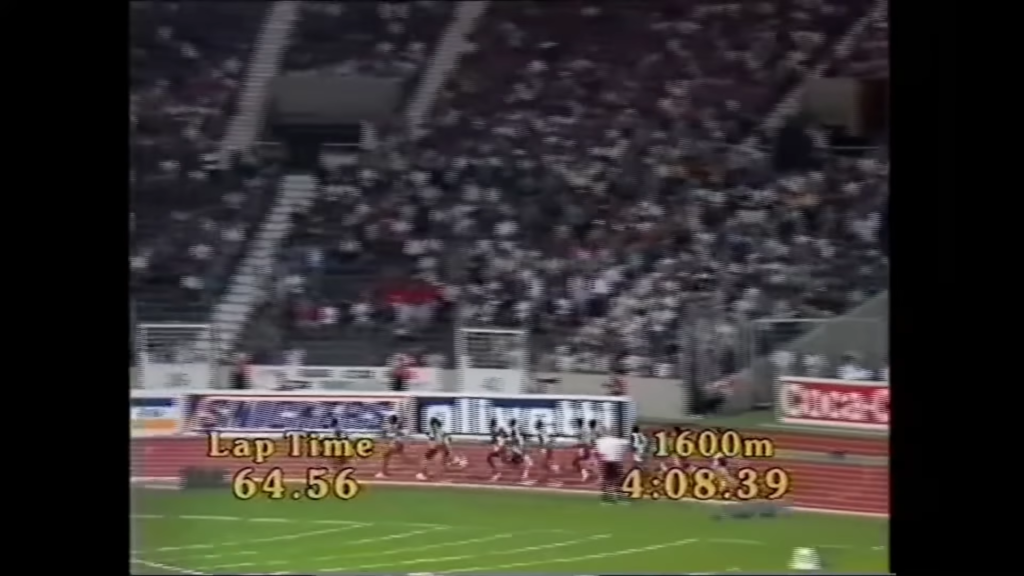

4:28 Chesire, with the major players just behind him now, hits 1600 in 4:08.39, which is 12:56 pace. The world record at the time? 12:58.

Walker: “Chesire still out in front. He still looks like the pacemaker to me. He can’t run all this way, he’s not good enough for a start. Kirui sitting back in third spot, he’ll be the one that’ll take off later on in the stages, I would say another two or three laps he’ll sit there for. They’ll try and outrun Skah.”

4:48 Kirui takes the lead just after the mile as McAvaney reminds us he’s still a teenager.

I have some questions about that, though. According to his World Athletics profile, Kirui was born February 20, 1975, which means he would have been just 18 at the time of this race. But that also means Kirui would have been only 15 when took 4th in the junior race at World XC and silver in the 10,000 at World Juniors in 1990. Obviously Kirui was a humongous talent, but that seems unlikely. I’m guessing he was probably in his early 20s in Stuttgart.

6:40 In researching this race, I read a few accounts that said the field let Kirui go because they didn’t consider him a serious threat to win. But that’s not the full story. As noted, Kirui had beaten Geb at World XC in ’92 and ran 13:06 to win in Lausanne a month before Worlds — a world leader at the time.

Rather, it was the severity of Kirui’s attack that allowed him to open a gap. When Kirui first surged to the lead, Skah responded immediately and moved into second — he knew to take Kirui seriously. But Kirui only split 62.88 for that lap. Kirui responded by coming over the top and ripping off a 60.21 lap from 2000 to 2400 to open a 40-meter gap. Understandably, no one responded to that as they still had more than half the distance let to run. Yes, the chasers made mistakes later by waiting too long to try to close down Kirui. But so far, Skah and Geb have been playing it smart.

8:07 Kirui passes 3k in 7:45.62, and if anything, his lead has grown. Incredibly gutsy stuff for a guy running his first senior champs on the track.

Gebrselassie has just moved to the front of the chase pack, which is rapidly thinning out. It’s down to Geb, Skah, and the two other Ethiopians, Fita Bayisa (the Olympic bronze medalist) and Worku Bikila.

8:35 Kirui just hit 3200 in 8:17.47 (still just under WR pace), and we’ve reached a critical moment of the race. Kirui still looks fantastic, but he’s slowing down — he just split a 63.50, his slowest lap since taking the lead. Skah, meanwhile, makes a push to the front of the chase pack. It looks as if Skah is going to try to chase Kirui down.

Instead, Skah hits the brakes and the chasers, who had been running single-file, begin to bunch up. The opportunity slips.

9:38 Kirui slows further, to 64.64 for his lap from 3200 to 3600, but his lead remains the same, 40 meters. Geb now finds himself leading the chasers as Walker tells us of an insane workout Skah just completed in St. Moritz: 20 x 400, averaging 57 seconds.

10:42 The chasers are behaving very strangely. All three Ethiopians (Geb, Bayisa, and Bikila) have spent time in second at some point over the last 150 — they all want to get up there, but none wants to do the work of reeling in Kirui (who has slowed again, clocking 64.74 for his last lap) once they get there. Skah, running fifth, seems tired.

12:18 Kirui runs another 64 to take him to 4400, and by the bell he still leads by five seconds. The crowd is starting to get loud.

We’ve seen people erase five-second gaps at the bell before, but Walker points out one confounding factor: the overall time is going to be very fast. When the chasers have been running close to world record pace, it’s suddenly a lot harder to find an extra five seconds on the final lap (the fast overall pace also explains why it was difficult for one of them to make an extended push after Kirui).

12:03.16 for Kirui at the bell.

12:32 First turn of the bell lap, and Bayisa and Geb quickly drop Bikila and Skah. Geb looks full of run, but rather than make the move into second, he elects to hang behind Bayisa, chopping his steps to avoid tripping him from behind.

This is a mistake. Kirui is still 30 meters ahead with 250 to go, and it’s no time to get cute. Geb needs to erase that gap ASAP, and he’s not going to do it quickly enough if he’s stuck behind Bayisa.

12:51 Kirui is 20 meters up with 200 to go. Geb is still in third.

13:00 150 to go. Geb still in third. The entire stadium is on its feet.

13:08 85 to go, and Geb finally passes Bayisa for second.

13:19 Geb unleashes a huge kick on the home straight, but it’s too little, too late. Kirui wins it in 13:02.75 (59.59 last lap) with Geb second in 13:03.17 (I had Geb in 55.9 with a 26.6 final 200). I feel fairly confident that Geb would have run this race had he kicked earlier.

That said, Kirui is the hero here. McAvaney spends a minute showering him with praise. All of it is deserved, and all of it remains 100% true, even 27 years later.

“It’s one of the greatest victories of all time. That’s as good as you’ll ever see…It’s one of the most inspiring and remarkable efforts in the history of athletics. That is not an exaggeration. That performance will go down in folklore as one of the greats.”

14:10 Final results. The top four set PBs, including a world junior record for Kirui and Ethiopian record for Gebrselassie (whose name is horribly misspelled). Chelimo’s defeat from ’92 is avenged, as Skah doesn’t even make it on the podium.

A few final thoughts on this race and the aftermath:

Quick Take #1: Putting Kirui’s run in context

If you watched the race, you know how impressive it was for Kirui to run 13:02 from the front in a World Championship final. But here are three more stats to put it in context.

-Kirui broke the meet record of 13:14.45 by over 11 seconds.

-Kirui’s 13:02.75 would end up as the fastest time run in all of 1993.

-When he ran it, Kirui’s time of 13:02.75 was the eighth-fastest time ever run, and just 4.36 seconds off the world record. That’s the equivalent of someone in 2020 running 12:44.90 (#8 time ever) or 12:41.71 (4.36 seconds off the WR) in the World Championship final.

Quick Take #2: Kirui is one of the greatest runners never to compete in an Olympics

Kirui would go on to claim silver and bronze at World XC in 1995 and 1996 and would repeat as 5,000m world champ in 1995. Yet he would never compete at the Olympic Games; in ’92, he was still running on the junior circuit, and in ’96 he developed an Achilles injury that would derail his career. Though he’d keep racing on the track through 2000 (he ran 13:11 that year), he was never quite the same.

It’s pretty crazy that two of Kenya’s biggest talents in the 1990s — Kirui and Daniel Komen (world records in 3,000 and 5,000) — never made it to the sport’s biggest stage.

Quick Take #3: Did this race scare off Geb from attempting the 5k/10k double at future championships?

1993 is the only time Geb ever tried the 5k/10k double at a global championship (he’d bounce back six days later and win the 10k, his first global gold on the track). Was his defeat to Kirui a factor in his decision to focus on the 10k at global champs for the rest of his track career?

Perhaps. The bigger factor, however, was likely the presence of qualifying heats in the 10k, which were in place at Worlds through 1997 and at the Olympics through 2000.

It’s a fun what-if though. This was the closest Geb ever came to the double — could he have won it if he kicked earlier? (I say yes).

***

That’s it for this week. See you next week for a recap of new races from Monaco!

*TBT #16: I Was Bored, So I Watched the 2005 NCAA Cross Country Championships

*TBT #15: I Was Bored, So I Watched Jenny Simpson’s Shock Gold at the 2011 Worlds

*TBT #14: I Was Bored, So I Watched the Greatest Marathon Ever — 2002 London

*Previous entries