What We Know About the Potential Changes to the NCAA Cross Country Regional System

By Jonathan Gault

June 1, 2020

Could change be coming to the NCAA cross country regional system?

Last week, a concept for a new regional system to qualify for the NCAA Division I Men’s & Women’s Cross Country Championships was leaked by The Stride Report. The concept, which was also provided to LetsRun.com, originated from the NCAA Division I Men’s and Women’s Track and Field and Cross Country Committee (MWTFCCC), a 12-person body consisting of NCAA coaches and administrators. The MWTFCCC has been charged by the Division I Championships Finance Review Working Group with exploring a new regional system that would reduce the number of regions from the current nine down to five and force teams to qualify for regionals.

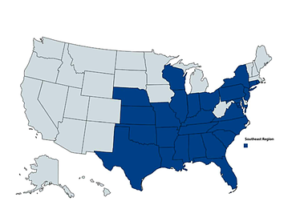

A key aspect of the concept: capping the number of entrants at each regional at 16, a significant change from the current model, where any team can compete at regionals. It also states that all schools from the same conference must be in the same region. As a result, you end up with some very odd looking regions — the Southeast Region includes teams from New York, Florida, Texas, and Nebraska.

Over the last week, college coaches, fans, athletes, and media have tried to make sense of this concept. Why does it look the way it does? Where did it come from? And why would the current regional system change?

After talking to a dozen NCAA coaches, this article is LetsRun’s attempt to make sense where things currently stand — and where things might go in the near future.

***

Why would the NCAA regional system change?

The current NCAA cross country regional system consists of nine regions, based on geography. The top two teams at each regional meet advance automatically to the NCAA championships, accounting for 18 of the 31 spots. The other 13 spots — the at-large qualifiers — are selected using an esoteric but effective qualifying formula (Editor’s note: The process starts by seeing which third-place team has the most number of wins against the automatic qualifiers; that team is added, and you repeat the process until you reach 31 teams). Since the regions are divided by geography, some are naturally stronger than others, but there is no limit to the number of teams one region can send to NCAAs. Last year, the Great Lakes Region sent a combined 11 men’s and women’s teams to NCAAs; the South Central Region, long dominated by Texas and Arkansas, has not sent more than the minimum of four since 2008.

“When they went from 22 teams [at NCAAs] to 31 teams in 1998, by taking 31, the goal was to make sure the top 25 teams in the country advanced,” says Harvard distance coach Alex Gibby. “And I think [the current system] has done that historically well. In a given year, I would argue that, historically speaking, you could make the argument that 28 or 29 of the top 31 teams advance. And sure, there’s always someone that comes on late or gets in off an odd result, an outlier if you will. But I think that’s the nature of sport.”

Almost every coach agrees with Gibby in that respect: the current regional system is not perfect, but if the purpose of regionals is to select the best teams to nationals, it does a very good job. The issue: some coaches want the regional system to do more than simply select the best teams.

Not all NCAA coaches believe the current system needs to be changed. But among those that do, the biggest reason is the belief that it is too difficult to qualify for the NCAA Cross Country Championships. 318 Division I schools sponsor men’s cross country; only 31 of them (9.75%) qualify for the NCAA championships. On the women’s side, just 31 of 348 (8.91%) make it to the big dance. No other Division I sport sends fewer than 18% of its teams to the NCAA championships.

On April 17, the NCAA MWTFCCC — the group that developed the concept discussed at the beginning of this article — issued a report in which it suggested “provid[ing] a percentage of access to NCAA postseason opportunities similar to other NCAA sports” was part of its reasoning for exploring a new regional model.

|

Not accounted for those cross country figures, however, is the fact that 246 men’s teams and 269 women’s teams competed at the NCAA regional championships in 2019. Regionals are not officially considered part of the NCAA Cross Country Championships even though they are, in essence, the “first round” of the NCAA cross country tournament. The problem, as some coaches see it, is that there’s no sense of accomplishment in competing at regionals if anyone can do it.

The solution: rebrand regionals as the official first round of the NCAA championships, and force teams to qualify for them. This would allow more teams to say they made it to NCAAs — around 20%, in line with other Division I sports — although the number of teams actually competing at regionals would drop from 515 to 160 (the current concept features 80 men’s teams and 80 women’s teams; it’s possible those numbers could go as low as 64 per gender). In so doing, it would provide a sense of accomplishment for mid-major schools that aren’t good enough to make NCAAs under the current system.

“Our experience with this could be really great if we sneak in and we have the opportunity to [be part of] a selection event,” says Siena coach John Kenworthy, who says he is also fine with the current system. “It feels like we made a national championship, just like our soccer team did or just like our basketball team does.”

Buffalo’s Vicki Mitchell, who also serves as the USTFCCCA’s Division I Cross Country President, supports a qualification system for regionals that, like other NCAA sports, would award automatic bids to conference champions.

“You win the conference championship, you come back to your school, everyone’s like, ‘That’s great, when are NCAAs?'” Mitchell says. “You’re like, oh, well, that’s not how we go to NCAAs. There’s going to be a lot of people that disagree in that aspect, aligning with other sports. I think it is a positive for our sport. I think it helps make our sport understandable.”

Many coaches, however, don’t see any point in changing the current format.

“Here’s what frustrates me,” says Oklahoma State coach Dave Smith. “When I talk to some of my coaching colleagues in the past about this idea of you have to qualify for regionals, the things they talk about are their bonus structures, being able to walk into their ADs’ offices and say ‘Hey, I qualified for the regional.’ Things along those lines that don’t seem to have anything to do with the good of the sport or what student-athletes prefer or what they want. I’ve coached for 20-something years. I’ve never had a student-athlete come up to me and say, ‘Hey why does school X, Y, or Z get to come to our region, they’re no good?’

“…What is the problem that this is trying to solve? What do we find that is so repulsive about the current system that we need to make dramatic changes and come up with some contrived exclusionary system to deny student-athletes opportunity and experience of competing in the regional championship?”

***

Who is driving this change?

NCAA coaches have long debated how and whether to change regionals, and support for change has grown over the past decade. It’s been a popular topic of discussion at the USTFCCCA convention, where in 2013, there was a motion to support the traditional nine-region format. It passed, overwhelmingly: 165 for, six against, three abstentions.

Three years later, UAB coach Matt Esche crafted a proposal to replace the current regional system. The idea was similar to the system currently used in outdoor track & field: a first round of the NCAA Cross Country Championships featuring 72 men’s teams and 72 women’s teams competing in two men’s races and two women’s races at a single site, with the top 16 teams in each race advancing to the NCAA final. That proposal was presented to USTFCCCA membership at the 2016 convention and voted down, with 72 in favor, 149 against, and two abstentions.

At the 2018 convention, several proposals for a new regional system were presented to the USTFCCCA Cross Country Executive Committee and ultimately struck down. That same year, Esche’s proposal was tweaked and presented by Wisconsin coach Mick Byrne to USTFCCCA membership. It failed, but the vote was the closest yet: 205 in favor, 222 against.

Even though Wisconsin hosts the Nuttycombe Invitational — the most important meet of the regular season under the current qualifying system because of the opportunity for teams around the country to earn at-large points — Byrne believes the current system is broken.

“It excludes a lot of schools from opportunities to qualify because we’ve got two or three mega meets,” Byrne says. “Obviously we’re one of them. But if you can’t go to those meets, you’re disadvantaged. And we shouldn’t have a system where schools are disadvantaged.”

That said, Byrne respects the outcome of the most recent USTFCCCA vote.

“I may not be in favor of it, but at the end of the day, this is what coaches really wanted,” Byrne says. “Okay, I have to live with that.”

And that is exactly why Byrne and numerous other coaches are so mad about the current situation. The new concept currently being explored did not originate from the coaches. It came from the NCAA MWTFCCC, at the request of the Division I Championships Finance Review Working Group.

But working groups don’t spontaneously generate ideas.

“I’m going to go out on a limb here: the only way the Finance [Review] Working Group believes that there is an issue is that there is a group of people or a person that have told something to them,” says New Mexico coach Joe Franklin. “The only way people want change, in all situations, is they become aware of a situation. So how do you become aware of a situation for cross country? If you go down through the fall sports — and I love our sport to death — we’re not on the tip of everybody’s tongue.”

At some point, someone decided it was time for a change. But neither Franklin nor Byrne has any idea who.

“This new proposal — god knows where it came out of,” Byrne says. “I don’t like it and I don’t like the idea that someone is telling us how to run our business. This should be coaches getting together and figuring it out…I don’t want the NCAA — or anyone else — telling us how to run our business.”

***

Where is the transparency?

I reached out to several members of the MWTFCCC and was told to funnel all questions to the committee’s chair, Milan Donley, the meet director of the Kansas Relays, who requested all questions for this story be emailed. Donley says that while the request to explore a new regional system came from the Finance Review Working Group, restructuring the regional system “has been a topic of discussion for many years.”

“There have been discussions from the coaches association as well as recommendations from the conference commissioners to run a regional qualifying model,” Donley says.

I also reached out to the NCAA to inquire about the Finance Review Working Group — which is not among the working groups listed on the NCAA website. I repeatedly asked an NCAA spokesman to provide the names the members of the working group; the spokesman refused, instead stating: “the Division I Championships Finance Review Working Group consists of members of all our Division I oversight committees that looks at all aspects of the Division I championships. It also includes a member of the Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee.” I requested to interview a member of the working group; the NCAA did not make anyone available. Donley also declined to answer who is on the working group.

The result: most NCAA coaches have no idea who, exactly, is driving this change, beyond a faceless NCAA working group.

“I would like to hear, officially, from the NCAA that the model that we currently have isn’t an option,” says Michigan State coach Walt Drenth. “I think there’s been a lot of speculation, and I’d like to see how our governing body could push back if that’s an option. I think that there has to be some transparency in how we’re approaching it.

“…I think there’s been some push from some influential people, it feels like, that are in favor of a change, and their influence is holding greater weight than an actual vote. I worry that we’re not being fairly represented in what our position is, as a group of coaches.”

Another issue among coaches I’ve spoken to: some are concerned that the future of the NCAA championships will be dictated by schools that will never participate in them. The NCAA committee charged with developing the new regional concept contains representatives from 11 schools. Only two of those schools, Kansas and Ohio State, have ever sent a team to the NCAA Cross Country Championships.

***

Complications with a new regional system

A few years ago, Andrea Grove-McDonough supported the idea of schools having to qualify for regionals. While at UConn from 2008 to 2013, Grove-McDonough took a program that had never been to NCAAs to an eighth-place finish at nationals in 2012. She felt that, for other schools looking to build their programs, qualifying for regionals would be a tangible sign of progress for both the coaches and athletes.

“I like the concept, but when you get down to the nitty-gritty of how you could do that, it has, over the years, started to feel more and more like, Hey, you know what? I like the system we have,” Grove-McDonough says. “It’s not perfect, but it may be as close as we’re going to get.”

Grove-McDonough is hardly alone. In an August 2019 survey of NCAA coaches, only 52 of 216 respondents (24%) said 100% of teams should advance to the first round of the NCAA postseason. The problem: creating a system that includes qualifying for regionals while remaining fair for teams and athletes is challenging.

“There’s a Winston Churchill quote that says, ‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others,'” says Northern Arizona coach Mike Smith. “I think that is our current regional system, which is one that frustrates a lot of people…The problem is, every time that really smart people dig deep into these other potential systems — and lots of them involve turning the regional meet from an all-comers meet into a qualifying meet — there are a series of unintended consequences that then make that another nightmare.”

Even with the parameters of a potential new system in place (five regions, schools must qualify for regionals, with conference champs earning an automatic bid), many questions remain, and not all of them have easy answers.

First and foremost: how are teams assigned to regions? The MWTFCCC concept leaked last week assigns teams based on conference affiliation rather than seed, which is inherently problematic.

“Any time you draw a geographical line, it’s impossible to make it fair, because it’s a little arbitrary,” says Washington coach Maurica Powell.

Assigning regions based on conference means at-large bids would be much harder to earn for schools in talent-rich regions. Which defeats the purpose of an at-large system.

“The at-large process in Division I championship sports is an avenue of access for all teams, regardless of geographic location or affiliation of conference,” says USTFCCCA CEO Sam Seemes. “…It’s supposed to be open or accessible to all, as it is in every sport. And in this model that we’ve seen, that’s not part of it. It’s restricted, so it’s not truly an at-large process.”

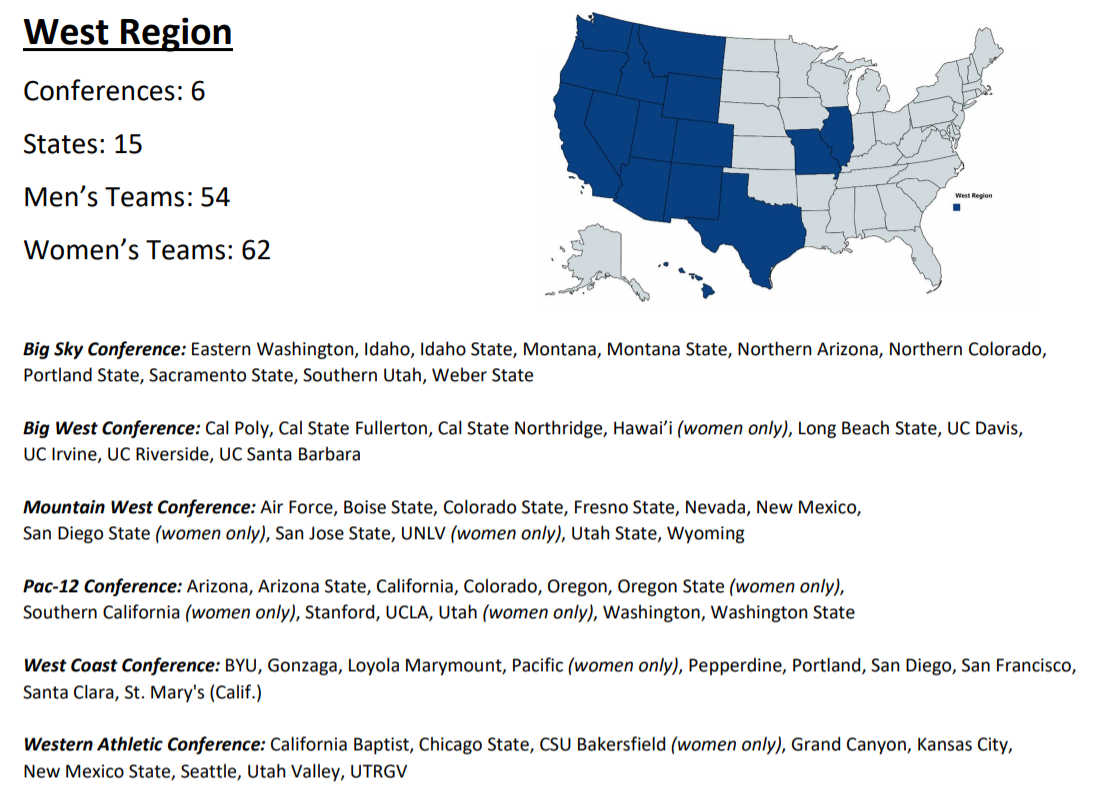

Consider: 12 of the 31 men’s teams who qualified for the 2018 NCAA Cross Country Championships — including the entire top six — came from schools in the West Region under the new concept. It would be significantly more difficult for a school in California to qualify for its regional meet than a school in Florida.

“You would never [put the top four seeds] in the same region — wouldn’t happen in golf,” says Franklin. “So why would it happen here? It doesn’t make equitable sense.”

See the proposed West Region in the new MWTFCCC NCAA regional concept:

The alternative — assigning teams to regionals based on seed — requires a lot more travel. And if a seeded model is adopted, what happens if a school’s men’s and women’s teams have the same coach but are sent to two different regions?

Another issue: does it make sense to hand all 32 conference champions automatic berths only to see several of them slaughtered at regionals? Should a conference champion like the Alabama State women (who finished last at the 2019 South Regional) or the Norfolk State men and women (who did not send scoring teams to the Southeast Regional) take spots from teams that could actually be competitive?

Of course, this happens in other sports — these are your 16 seeds in the NCAA basketball tournament. And that gets us to one of the debates at the heart of overhauling the regional system. Those in favor of change believe cross country should align itself with other NCAA sports — which means more teams qualifying for the NCAA championships. Other coaches believe alignment is unnecessary; the current system works, so why change it?

“Alignment is a wonderful concept,” says Gibby. “But the devil’s in the details. We are unlike other sports.”

Other issues that need to be straightened out with a new regional concept:

How will the at-large selection system work? One of the common solutions is the creation of an RPI system, similar to basketball and other NCAA sports. But that presents another problem.

“I don’t know that we have enough data to give us information to put together an RPI,” Byrne says. “When we only have three to four meets a year that count before regionals, the data is different. Basketball, look at the number of games they have. And a lot of the other sports, they’ve got a lot more competitions, opportunities, to build that RPI.”

Byrne supported the Esche proposal because he believed it meant teams would not have to fly all around the country to chase at-large points. But some coaches are worried an RPI system will result in more travel, not less.

“Because the bigger body of work you have, you may be able to game the system, the better your RPI will be,” says Grove-McDonough.

That presents another knock-on effect: coaches are worried that, if teams are expected to race more frequently than under the current system, they could risk burning out athletes who are already expected to race hard for three seasons per year.

As for qualifying from the new regional meets to the national championship, Donley says the current Kolas model would still be used. Which could mean there is one set of criteria to qualify for regionals and another, different set of criteria to qualify from regionals to NCAAs.

Will this save money? Since the NCAA’s Finance Review Working Group is the body pushing for change, it’s logical to conclude reducing costs might be a goal of the new regional system. It’s unclear how well that will happen.

According to the Esche proposal, the NCAA currently spends a total of approximately $180,000 to $200,000 per year on the nine regional meets, with the host institutions are collectively spending another $100,000 to $200,000 per year. These are merely estimates — Franklin says New Mexico, scheduled to host the Mountain Regional in 2020, submitted a budget of $13,607.76 for this year’s meet, which would be entirely reimbursed by the NCAA. But even if the NCAA spends $200,000 per year, cutting back to five regional meets would save the NCAA at most $90,000 — a drop in the bucket for an organization bringing in $1 billion a year in revenue. Though it would also streamline the regional system, as the NCAA would not need to find as many hosts institutions.

What about individual schools? Under the new system, four schools would save money by not having to host regional meets each year. But overall, most schools would likely end up paying the same or, perhaps, significantly more.

Currently, the NCAA doesn’t pay for schools’ travel to regionals. That is not going to change, no matter what model is adopted. But under the current system, teams can at least plan their travel to regionals well in advance. If the NCAA decides to assign teams to a region by seed, rather than geography, “costs are gonna skyrocket,” according to Franklin. Trips to regionals will be longer, and teams won’t know where they’re going until after their conference meet.

“Trying to buy tickets within a 10-day window for upwards of 20 people to fly? The outlays there are going to be ridiculous,” Gibby says, noting many smaller schools are just struggling to keep programs afloat during the coronavirus pandemic. “And so how mid-major teams function, particularly in our current environment? I think that’s really disconcerting. I think ADs are gonna look at this, see the numbers, and be like: are you kidding me?“

Appalachian State’s Mike Curcio — whose men’s team could benefit from the new system, considering the Mountaineers won the Sun Belt Conference last year but only finished 15th at the Southeast Regional — cited a similar reason for why he’s “not particularly for change.”

“I like the system the way it is because it gives access to every team,” Curcio says. “Institutions can make the decision. Institutions are paying for it. I can get to this regional site, if our institution deems that we’re worthy to go…If we’re gonna have to fly somewhere, and I won’t know whether I’m gonna be getting an at-large bid, I would have to be scrambling to get flights at the last minute.”

***

Where do things stand now?

Any change to the regional system would have to be ratified by the NCAA Division I Competition Oversight Committee. And currently, the MWTFCCC does not even have a proposal. All they have are parameters from the Finance Review Working Group. The leaked MWTFCCC concept fit within those parameters, but given the opposition from many coaches — including the Big 10 coaches, who signed a letter opposing it — it will likely have to be refined before anything is presented to the Competition Oversight Committee. And Mitchell, the USTFCCCA Division I Cross Country President, believes the coaches can still have a say in that.

“I do believe that the [MWTFCCC] want our input as coaches and they want feedback from us,” Mitchell says.

In addition, the MWTFCCC has said the new concept being discussed would not come into effect until 2022 at the earliest (it’s possible the NCAA may have to create another system for this fall, given the travel difficulties and possible reduction of competition opportunities imposed by the coronavirus, but that’s another story).

One of the biggest unanswered questions right now: does the fact that the MWTFCCC has been tasked with exploring a new regional concept mean that the regional system is definitely changing?

The answer depends on who you ask. Donley, the chair of the MWTFCCC, did not say change is 100% certain, but appeared to indicate some form of change is coming.

“The committee continues to review a qualifying model and has welcomed the feedback and input of the membership,” Donley says. “Eventually a formalized model will go to the Championship Oversight Committee for their review and approval.”

Mitchell is one of several coaches who believes change is “inevitable” — the only question is how the system changes. Others aren’t as sure.

“I’ve been told by some that ‘the train has left the station’ — at this point, this is going to happen, and the only thing you can do now is hope to mitigate what it looks like or how much of an impact it’s gonna have,” Smith says. “Others have told me no, it hasn’t left the station, but it’s definitely boarding up, and if coaches or conferences or institutions have a strong feeling about it, one way or the other, they need to be active, quickly and emphatically, to get their opinions heard.

“We are the NCAA. To say the NCAA wants this — there’s more than 10,000 people in the NCAA, and they don’t all want this. There is a small subset of people within the NCAA that want this. But the vast majority do not think this is a good idea.

“If we act now, we can stop it. We can reverse it. But it can’t just be a letter from Dave Smith. There’s gotta be some weight behind this.”

To that end, Smith has begun rallying coaches behind him to preserve the current system, including Drenth and Gibby. Even Byrne, who has butted heads with Smith in the past when it comes to regionals, agrees that the leaked MWTFCCC concept cannot be allowed to pass.

“If’ we’re going to stop it, we need to stop it now,” Byrne says. “It’s very time-sensitive.”

Talk about the proposed changes to NCAA xc on our messageboard / fan forum: MB: NCAA Cross Qualifying Changes?