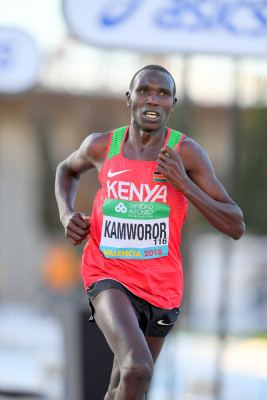

The Greatness of Geoffrey Kamworor: Where Does the Kenyan Star Go From Here?

By Jonathan Gault

April 6, 2018

Geoffrey Kamworor does things that other humans cannot. Two years ago, at the World Half Marathon Championships in Cardiff, Kamworor slipped at the start line. He was on the ground for seven seconds before he was able to stand up again. For a lesser athlete, the race might have been over right there. Kamworor had spotted some of the best runners in the world — including Mo Farah (now a four-time Olympic gold medalist) and Bedan Karoki (now a 58:42 half marathoner) — a big early lead. What’s more, to rejoin the leaders, he would have to navigate hundreds of bodies, courtesy of the mass race that started right behind the elites. Yet within 90 seconds of picking himself up, Kamworor was back with the leaders, the result of running close to 4:00/mile pace while dodging lesser athletes. Kamworor went on to win the race by 26 seconds in 59:10 on a wet and windy day in South Wales, crossing the finish line with his kneecaps still bloodied from the fall at the start.

For most elite runners, that would be the performance of a lifetime. But by the time the 25-year-old Kamworor’s career is over, it may be just one of many mind-bending performances on the Kenyan’s résumé. The latest came in Valencia on March 24, at the 2018 World Half Marathon Championships, in which Kamworor unleashed one of the most astonishing splits in the history of distance running — 13:01 from 15k to 20k — to win his third straight title in 60:02. Yes, that segment is a net downhill, and Kamworor benefited from a tailwind as high as 30 mph for much of it. But even after slapping the requisite qualifiers on the performance, it’s still impressive as hell. His legs were still moving at 4:11/mile pace for those five kilometers (if you add on the final 1.1k of the 21.1k race, his average pace actually speeds up since he picked it up to the finish) and it should come as no surprise to learn he dropped the third-fastest man in history, Bahrain’s Abraham Cheroben, putting 20 seconds on him by the finish line.

13:01 is mind-bogglingly fast. The U.S.’s Paul Chelimo is one of the world’s best 5,000-meter runners, earning medals at the 2016 Olympics and 2017 Worlds. His personal best, on the track, in spikes, is 13:03.

But because Geoffrey Kamworor can do things that other humans cannot, it does not strike him as particularly odd when he actually does them. Like, say, splitting 13:01 during a half marathon.

“To me, it wasn’t a surprise,” Kamworor tells me in a phone interview on Wednesday. “Because it’s something which is possible that I can do.”

It’s a refreshingly simple way of looking at things. And it also gets to the quality that everyone who spends time with Kamworor notices: his confidence.

I ask him if he thinks he can break the half marathon world record.

“Yeah, it’s something I believe I can [do], and with time, I will plan. To me, it’s possible, yeah, for sure.”

What about the marathon world record?

“Yeah, for sure, it is something I would like to do.”

If Kamworor thinks he can do something, he’s not afraid to talk about it. No bravado. No arrogance. He just says it, as if these ridiculous acts are the most natural thing in the world to him. I knew I was going to run fast. 13:01 is fast. What’s so strange about that?

***

That confidence is what convinced Valentijn Trouw to take a chance on Kamworor back in 2010. Trouw is an athlete manager at Global Sports Communication, the Dutch agency led by Jos Hermens that manages the athlete training camp in Kaptagat that has produced Stephen Kiprotich and Eliud Kipchoge, the last two Olympic marathon champions. Every fall, Trouw travels to Kenya to check in on the camp and decide which new athletes to bring in.

On the recommendation of Patrick Sang, Trouw met Geoffrey Kipsang Kamworor (pronounced JOFF-ree) for the first time on one of these trips in November 2010. The 1992 Olympic silver medalist in the steeplechase, Sang, now 53, serves as the coach for the athletes in the Kaptagat camp and had noticed Kamworor at a local road race. While Kamworor possessed some talent, running 13:42 for 5,000 at age 17, it was the way he carried himself that impressed Trouw.

Trouw began by asking what Kamworor’s dreams were for later on in his career. Kamworor responded, calmly and clearly, by stating that he wanted to break the half marathon world record and then move on to the marathon — the same path followed by the late Sammy Wanjiru, the 2008 Olympic marathon champ. He said this in the same matter-of-fact manner in which he described his 13:01 in Valencia.

“From the first moment you met him and you spoke with him, it was clear that you were sitting with a future top athlete,” Trouw says.

Convinced of his greatness, Trouw signed Kamworor and brought him into the camp.

He was not the only one Kamworor impressed early on. Kamworor was just 18 years old when he was signed up to pace the 2011 Berlin Marathon, which featured world record holder Haile Gebrselassie of Ethiopia. But during the 28th kilometer, breathing problems forced Geb to stop, and when he stepped back onto the course, the lead pack had left him behind. At that point Kamworor, who had run world record pace with Patrick Makau (who would go on to break Geb’s WR in that race) through 28k, dropped back and served as Geb’s personal rabbit for the next seven kilometers before Geb ultimately dropped out. That performance, and his subsequent 2:06:12 debut in Berlin the following year, earned him high praise from Geb.

“Believe me, if he keeps with this style or this training, this result, he will be the one who can break the world record,” Gebrselassie said after Kamworor’s marathon debut in 2012, speaking in The Unknown Runner, a documentary about Kamworor’s life (rent/stream here).

Signing with Global was the break Kamworor had been waiting for. He had always been the fastest of his friends in his home village of Chepkorio in Kenya’s Rift Valley, and before he even entered high school, he had plenty of miles under his belt. His primary school was three kilometers from his house, and since Kamworor would return home for lunch, he ran that route four times daily growing up. While a student at Lelboinet High School, Kamworor began running competitively following the encouragement of his chemistry teacher. After his final year there, in 2010, the 17-year-old Kamworor and his friends pooled their money so that he could travel to Finland to pursue his running dream and try to secure a professional contract.

He had no coach, and his racing spikes weren’t really “spikes” at all, considering Kamworor ran several races without any spikes in the bottom of the shoe. In all, he raced 11 times in Finland in the span of 11 weeks, including a brutal stretch in June in which he raced a 5k, 3k, and another 5k in the span of four days.

While Kamworor finished first or second in 9 of his 11 races (running pbs of 3:48, 7:54 and 13:42), Kamworor did not enjoy the trip. As he suffered through race after race, Kamworor dreamed of joining a professional group. One in particular: Patrick Sang’s.

“It really motivated me,” Kamworor said. “I really didn’t want to go back [to Finland]. So when I came back, I really trained hard because I wanted to be in a good place, good management.”

It didn’t take long for the move to Kaptagat to begin paying dividends. In March 2011, just four months after joining Sang’s training group, Kamworor won the junior race at the World Cross Country Championships in Punta Umbría, Spain. In the ensuing years, under Sang’s tutelage, Kamworor has become one of the world’s greatest distance runners. In 2012, he ran 2:06 in Berlin, in 2013 he ran 58:54 to win the prestigious RAK Half Marathon, and every year since then, he’s won a world title, either World Half (even years) or World Cross (odd years). Last fall, he added his first major marathon title, blitzing the 25th mile in 4:31 and then holding off Wilson Kipsang to win the New York City Marathon in 2:10:53.

When you listen to Kamworor explain his rise, it all seems so simple. Be disciplined. Work hard. If you’re training for the marathon, add in a few more long runs. When you’re training for the track, add in a few more interval sessions.

And that is the beauty of Sang’s system, for he is as much a life coach as a running coach. He has instilled a culture in which love of the sport and work ethic are prized above all, where the trappings of material wealth — the undoing of many a promising Kenyan runner — are pushed off to the side. Athletes like Kamworor can visit their family during weekends — he has a wife, Joy, and two young children, three-year-old Elsie and six-month-old Elvin, in nearby Eldoret — but from December through September, Kamworor lives in the Global camp in Kaptagat, where he splits chores with the two-dozen other residents.

For such an accomplished training group, the camp lacks several modern amenities. The only weight you will find there is a metal bar with a cement block on each end. The local track at Moi University is dirt, with no lane markings. The toilets aren’t really toilets, just stalls consisting of three walls with a trough at the bottom. But the camp serves its purpose: it gives the athletes little option but to pour everything they have into training and recovering. It also keeps them humble — it’s hard to be cocky when it’s your turn to clean out the bathrooms.

Sang knows how to train runners, too, of course. When Nike’s scientists examined the training of the three athletes in last year’s Breaking2 attempt, Kipchoge’s was the only one they did not try to alter; he was already doing everything right. But the details of the specific workouts aren’t as important as the development of a culture in which distractions are eliminated and the immense natural talent of athletes such as Kipchoge and Kamworor is allowed to flourish.

And if you find the right leaders, that culture can become self-sustaining. Kipchoge has long been Sang’s model pupil, and his discipline and success have won him the admiration of the rest of the group, Kamworor included (he refers to Kipchoge as “my mentor”). In 2016, Kipchoge gave him a pair of his old racing spikes. The spikes inspired Kamworor, and he wore them during his victory at 2017 World XC, proudly showing them off to the media following the race.

Now that the spikes have been worn by both Kipchoge and Kamworor, they’ve become something of an heirloom, and while they would fetch a nice price from any collector of track & field memorabilia, Kamworor is holding onto them for now. But he’s willing to pay it forward, should a worthy successor emerge.

“Maybe I will have to give [them] to someone else to motivate [them].”

***

Though Kamworor’s most recent world title is not yet two weeks old, running is a sport obsessed with the future. Which means the natural question, as with any athlete who runs well in any race, anywhere, is “What’s next?”

As usual, Kamworor makes it incredibly simple.

“I want to win as many medals as possible in championships,” he says.

In the near-term, Kamworor will run some Diamond League races at either 5,000 or 10,000 meters before embarking on a fall marathon, likely New York, where he wants to defend his title. Long-term, he wants to become Olympic champion in 2020, though he hasn’t decided whether he wants to run the 10,000 or the marathon.

But even an athlete as talented as Kamworor can’t do everything. Trouw thinks that Kamworor has the ability to take a serious run at Zersenay Tadese‘s half marathon world record of 58:23, but fitting a record attempt into a schedule that includes either World XC or the World Half in the spring, track in the summer, and a marathon in the fall is nearly impossible.

“Because he is combining the half marathon, the cross country, the track, the marathon, you can see in his race profile the last two or three years, he isn’t able to run a lot of half marathons,” Trouw says. “I don’t think it’s ideal to do it in a buildup towards a full marathon, so then already one season is gone. And when you are focusing towards the track, it’s also not perfect. It’s a bit hard. Sometime in February could be a good time, but February, normally he’s doing nationals in Kenya to qualify for a championship. So it’s not easy to find the right race and the right time to make [the world record] a goal in itself.”

Indeed, since the start of 2015, Kamworor has run just two half marathons, which came at the World Half Champs in 2016 and 2018. Trouw says that while he still needs to talk to Kamworor to map out the next few years, he has a hunch how the next few years will play out.

“What I feel a little bit is until Tokyo 2020, the Olympics, that he will continue the way he’s doing now, to combine the different fields of track and field, and half marathon, and cross country, and full marathon,” Trouw says. “And maybe after Tokyo 2020, that could be [when] he wants to run really fast in the marathon.

“…He is still learning the marathon. I think the half marathon and the cross country, is when you see somebody who [is] feeling [in] complete control…When you speak about Valencia, it really didn’t matter for him if it was fast from the start, or if it was a slow race and fast towards the finish. Any kind of tactics suits him well.”

***

Watching Kamworor run for the last few years, it was obvious that he was different, but interviewing him for this story confirmed it. I want to know how he stays motivated, despite all his success. His response surprises me.

“A gold medal always motivates me to work hard for the next year,” Kamworor replies. “It really motivates me a lot to go for more in future.”

That’s not how it’s supposed to work. The cliché is that failure is the greatest motivator, and in my experience as a sports journalist, that’s mostly true. Not for Geoffrey Kamworor. Winning doesn’t make him want to relax; it makes him want to win the next one even more.

“He doesn’t look back,” said Richard Meto, Sang’s assistant coach, in The Unknown Runner. “The others we have here [in the Global camp] run and look back, but he doesn’t look. When he’s focused ahead, he’s ahead. He doesn’t care who is there. He moves.”

And even when asked to look back, he can’t help but look forward. Of all his victories, I ask Kamworor, which does he think is the best?

He doesn’t respond with Cardiff, or New York, or Valencia, but rather the one gold medal he has yet to attain.

“I think the Olympics is the one I’m really looking forward to achieve.”

More: Talk about what’s next for Kamworor on the messageboard: MB: What’s next for Kamworor ?

*Rent or buy The Unknown Runner here