Mud, Beer, and VIKINGS! A Behind-the-Scenes Look at How the Incredible 2019 World XC Course Was Designed

Next week’s World Cross Country Championships will be held in Aarhus, Denmark, and the organizers are planning one hell of a party. The course features a beer tent, a portion that runs over the roof of a museum, and a Viking Zone. And it’s all inspired by Chuck Norris.

By Jonathan Gault

March 20, 2019

When Jakob Larsen and his team began planning the 2019 World Cross Country Championships, he was certain of one thing.

“The very first brainstorm session we had, everyone agreed: no matter what, we will not have Vikings,” says Larsen, director of the Danish Athletic Federation and the Local Organizing Committee of the 2019 World XC Champs, which will be held in Aarhus on March 30. “Because being Danish, you kind of get fed up with it.”

Specifically, Larsen showed everybody in the room this image:

That idea didn’t last long.

“Then the IAAF came,” Larsen says, “and the first thing that they said when they arrived was ‘you should do something with Vikings.'”

So Larsen decided that if they were going to have Vikings, they were going to do it their way. “Biker Vikings” was the phrase he had in mind.

“The Karsten Warholm helmet, plastic helmet with horns, for us, that’s the Disney version,” Larsen says. “Real Vikings is like the HBO series Vikings. It’s more tough. It’s not fairy country. It has to signal the toughness that goes with cross country.”

Larsen hired a local group of actors and earlier this year, he set up a meeting with their leader at the Moesgaard Museum, site of the race, to figure out the best place on the course to position the Viking Zone. Larsen hadn’t met the man before and wasn’t sure who to look for. Then he saw someone dressed in full Viking attire, shield, ax, and spear at the ready. Even for logistics meetings, Larsen’s Vikings come prepared.

“These guys are very dedicated,” Larsen says.

Larsen’s idea was to recreate what it felt like to “run the gauntlet” — an old military punishment where the culprit would strip off his shirt and be forced to run between two rows of soldiers, who would whip and beat him with weapons as he passed.

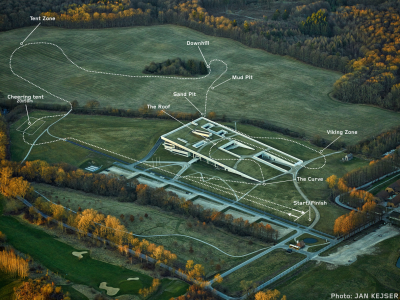

About a mile into the two-kilometer loop that forms the basis of the course, 30 of Larsen’s Vikings will have their own miniature village, complete with bonfires. The weapons will be fake — and they won’t be used for beatings — but he’s hoping that the atmosphere they create feels quite real.

“When people run through it, they will know that they’re in Viking territory,” Larsen says.

Stephanie Bruce, who finished 22nd at World XC in 2017 and will represent the US again in 2019, believes that’s a good thing.

“When you’re running in races, you know the parts that are really silent on a course, they’re really difficult for athletes because no one’s around and sometimes people lose motivation or you’re having a rough patch,” Bruce says. “But anytime you can run by cheering fans or people yelling at you, I feel like you get a boost of energy. So I think that can only be positive for the race. I mean hopefully they’re not yelling, You suck!“

***

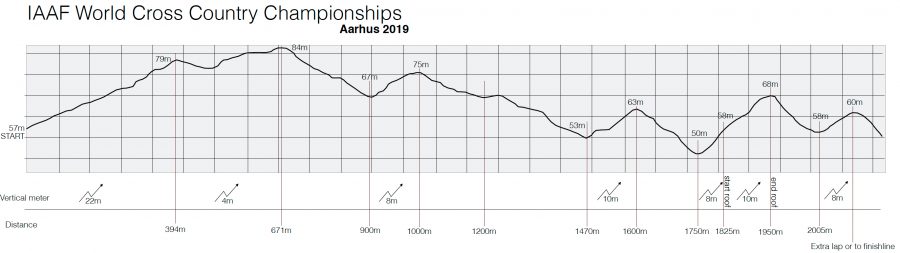

When the world’s best distance runners (well, some of them, at least) arrive in Aarhus, Denmark’s second-largest city, later this month, they’ll be greeted by a World XC course unlike any in recent memory. The Viking Zone is just one of half a dozen features that sets the race, which will be contested on the grounds of the Moesgaard Museum, barely a mile from the Bay of Aarhus on the east coast of Denmark’s Jutland peninsula, apart from recent editions. It starts with the elevation profile of the main 2k loop (the senior men and women will run it five times each), which resembles the blueprints for a rollercoaster. And it’s tough from the gun: the course climbs 72 feet within the first 400 meters.

Then there’s the “Runner’s Valhalla,” a massive 50x20m tent/cheering zone, where fans are encouraged to drink beer and get up-close and personal with the athletes. There’s the roughly 200-meter segment of the course that runs on the grass roof of the Moesgaard Museum itself as well as the man-made water, sand, and mud pits. Oh, and did we mention the whole thing is sponsored by Mikkeller, a Danish microbrewery? (It helps that Mikkeller co-founder and namesake Mikkel Borg Bjergsø is a runner himself, having placed 166th in the junior race at World XC in 1994).

Thomas Glud, who in his role as LOC technical manager is one of the three people — along with Larsen and competition coordinator Katrine Gribel Vorum — who designed the course, wanted to make sure that this year’s championships had a different feel from the last World XC, held in Kampala, Uganda, in 2017.

“I looked at it on television and I saw this championship on a total flat field in Uganda,” Glud says. “I think, ‘Oh my god, what is that? There’s no action. This is not cross country as I think it is.’… Jakob agreed with me and said, ‘We do it totally different from Uganda.'”

Running in the race, Bruce felt similarly.

“Honestly, Uganda wasn’t that hard of a course to me,” Bruce says. “I think just because it was at 3:00 in the afternoon and it was so hot and humid, it just felt like the sun was beating down on us. But the difficulty of the course there didn’t seem that challenging compared to what I’m seeing from this course profile [in Aarhus]. I like the challenge. I think that’s why you run cross country.”

At this point, Glud knows the course in Aarhus like the back of his hand — he lives a two-minute walk from the course and has been visiting the site roughly three times a week for the past two years. Working with an overall event budget of roughly $2.5 million, the LOC began construction of the final, temporary elements of the course on Monday, and their vision is clear, with a two-pronged approach aiming to satisfy both the athletes and the fans.

Larsen is expecting at least 5,000 fans on race day — more if the weather cooperates — and has tried to cater the event as much to their needs as to the needs of the athletes.

“Of course we should never forget the athletes, but as organizers, we often tend to focus on the athletes exclusively and somehow forget that there are people out there that, all they want to do is they want to have a return on investment,” Larsen says. “They are investing time to go to the venue or watch it on the television, etc., and we need to provide a return of investment on that. That’s our job.

“It’s an event. It’s a spectacle. The tricky part about cross country is that it’s a very long event. You have five races. It goes on forever and ever. We need to be able to provide entertainment for five hours of live television. But we also need to provide highlights that will work for like 10 seconds, 15 seconds, that will work on social media.”

So that’s what Larsen and his team had in mind when designing the course: what sort of features would look great in photos or a 15-second video clip? They knew they wanted mud, because cross country just looks better when there’s mud splattered all over an athlete’s legs, arms, and singlet. For the rest of the features, they drew inspiration from the most highlight-worthy sections of other events.

Larsen thought about cross country equestrian (basically the steeplechase with horses), where fans would always gather around the water pit. So they added a “splash zone,” a six-inch deep pit filled with water.

He thought about the Alpe d’Huez, the most famous climb in the Tour de France, when designing the section of the course that runs on the roof of the Moesgaard Museum; not only is it the steepest climb on the World XC course, at a grade of 10%, but it is Larsen’s hope that the crowds will, well, crowd the athletes as they make the climb, just like the notoriously passionate fans at Alpe d’Huez.

The Runner’s Valhalla functions similarly to the tent at the Night of the 10,000m PBs event in England, a large, covered section where it feels like the race is passing through a night out at the pub. And while Larsen says the inspiration for the Runner’s Valhalla, which will also feature a DJ, actually comes from the Frankfurt Marathon — which finishes inside Festhalle Frankfurt, an arena replete with exotic light shows and loud music — part of the tent will in fact be styled like a British pub and serve as a designated meeting point for former elite national and international runners. So old-timers can quite literally stand around, beer in hand, and reminisce about the good ol’ days — as the current generation whooshes by them.

“Obviously anytime you can get fans drinking watching running, that’s a good thing,” Bruce says.

One thing you might notice that most of these features have in common: they make the course more challenging. That’s not by accident. It’s part of Larsen’s philosophy. Call it the Chuck Norris school of course design.

During the planning process, Larsen was meeting with an advertising agency. As they were unfamiliar with the sport, Larsen tried to explain World XC to them.

“I said, okay, this is the most difficult event to win,” Larsen says. “That’s my personal opinion — this is by far the most difficult running event to win.”

They told him if it’s really that tough, he had to invite the toughest person they could think of: Chuck Norris.

“Which makes absolutely no sense of course, but then again it does kind of make sense because it says, yeah, this should be fun,” Larsen says.

And that led to the basic formula for the course: tough + fun = World XC.

***

Perhaps the most interesting facet of this year’s World XC champs is that, for 999 Danish Krone ($151) anyone — well any man who has broken 33:00 or women who has broken 37:00 for 10k within the last 12 months — can sign up to run alongside the pros in the championship race. These non-championship runners won’t count in the individual or team scoring — so even if Eliud Kipchoge shows up and wins the thing, he won’t get the gold medal — and will be pulled off the course if they’re about to be lapped. But otherwise, they can run the same course, at the same time, as the best runners on the planet. Larsen says he hasn’t looked into the entries in detail yet, but says that “a top 10 runner from the Euros” has entered as part of the non-championship field.

Like most of his innovations, Larsen says adding more runners into the senior races was rooted in creating better visuals.

“If you look at standard World Cross Country Championships, the gantry is huge,” Larsen says. “So you have the start and finish line, which is, like, 30 meters wide. And there are almost no runners there compared to the size of the gantry. And from a television perspective, this just looks totally stupid.”

He wants World XC to look more like the English National Cross Country Championships, where the start resembles the charge of the Rohirrim at Pelennor Fields. When the gun goes off, Larsen wants everyone watching to think to themselves, now that’s a race!

https://twitter.com/LILforeigner/status/1099352101187186701

Article by John Walshe reflecting on this years English National Cross-Country Championships and the one in 1979 in Luton… https://t.co/XrVYnc8vcZ pic.twitter.com/k51ocX1OAd

— Running in Cork Blog (@runningincork) February 27, 2019

World XC will not be quite as large as the English champs, which had over 2,000 finishers in the men’s senior race this year. Race organizers are capping the fields for each 10k race at 400 — that includes championship and non-championship runners — but the cap appears unlikely to be necessary; as of today, approximately 50 people have signed up to run the non-championship section, to go with 159 men and 131 women in the championship fields.

“I expected more, and there’s still time, but I guess the overall concept is not quite right yet — although I personally believe this is the right way to go, ” Larsen says. “We just need to figure out the right way to do this.”

But it’s not all about what will look good on TV. When Copenhagen hosted the World Half Marathon Championships in 2014, it incorporated a mass race into the event, and Larsen believes that is a vital component to ensuring that a running event is successful in the year 2019.

“If cross country is to keep being relevant — or to become relevant, I could argue — we need to bring more resources into the sport, and the only way to bring more resources is to have more people on-site,” Larsen says, adding that they had initially considered running the championship races on a single 10-kilometer loop to allow even more people to participate at once. Instead, there will be other opportunities for fans to race on the course on race day — a 2k “sprint,” a 4x2k relay, and a 4k/8k/12k race that will be run half on trails and half on the World XC course itself. All of these mass participation races will be held in the afternoon, after the championship races are over.

“I do in fact consider running to be a participant sport,” Larsen says. “So step #1, ensure that a lot of people can actually take part in this. Then there will be spectators as well. From a Danish perspective, that would be how it goes.

“We can bring all the best runners in the world to Denmark and there will be spectators. But if we can ensure that they have family members running on-site or indeed, that the Crown Prince will run — which he will — that’s a completely different discussion. Then there will be a lot more people.”

Larsen says that, as of Wednesday, approximately 1,500 people had signed up to run in one of the mass participation races, though there is one man who has yet to enter. A certain American action movie star known for his roundhouse kicks.

“I read that Chuck Norris has his own 5k race now,” says Larsen, adding that they considered reaching out to Norris but did not actually end up inviting him. “I guess that means that he’s not coming to World Cross Country. So by extension, that means he’s not the world’s toughest runner. He would be able to run, but he wouldn’t be able to win.”

***

All of this sounds like a great day out, but will it resonate? Even if the mud and the roof and the Runner’s Valhalla all work as planned and generate a storm of tweets and Instagram likes, will it have any effect on an event that has struggled for relevance this decade? In 2011, World XC switched from an annual to biennial format, and aside from a few athletes — such as two-time defending senior men’s champion Geoffrey Kamworor — who build their season around it, most runners don’t view it as a must-race event. Mo Farah raced World XC five times between 2003 and 2010, but none since developing into the best distance runner of the 2010s. Galen Rupp, America’s best distance runner this decade, has never run the senior race at World XC. The women’s race at this year’s USA XC champs featured one of the most competitive fields of American women ever assembled, yet four of the top five finishers in that race declined their spot on Team USA for Worlds.

It’s not just individual athletes who don’t feel it’s necessary to go to World XC. Aside from Poland when they hosted the championships in 2013, only one European federation has sent a full squad of either six men or six women to a senior race at the last three championships (the Great Britain women in 2013). Only 13 European men, total, competed in the senior race at the last World XC; only Spain and Denmark sent enough men to score as a team. It was worse on the women’s side: 11 senior European athletes, with only GB and Spain sending enough to score.

The complaint is that the Africans are too dominant, so why bother sending a full team? And while it’s true that Kenya and Ethiopia would still be likely to prevail even if every country sent its finest, it’s partly a self-fulfilling prophecy: if you don’t send anyone to compete with the Africans, then how could you ever hope to beat them?

“In my opinion, I think it’s an important discussion for the running community and for the federations what role cross country has,” says Larsen, who should not be immune from criticism — Denmark sent a grand total of zero men to World XC in 2015. “Is cross country a potential addition to the business of running? Is it purely a competition like the half marathon was before Copenhagen? Is this an essential part of our culture? Because whatever the choice is, people need to adjust their behavior.

“Right now I would say that some federations, I think they are disregarding the importance of the running community. I think that they are forgetting the level of interest, if properly handled, this could generate within their running community. It’s especially European countries, I would say. European countries, they risk being disconnected from the running community if they do not back the running championships, like the cross country, like the half marathon. If they do not send significant teams, but choose only to go if they have a top-20 athlete, I think that’s a huge risk to take, in my opinion.”

After Aarhus, World XC’s next stop is Bathurst 2021, an Australian city three hours west of Sydney — about as isolated a location as you’ll find for a global running championship. Can they match the course and enthusiasm of Aarhus? And will anyone show up even if they do?