LetsRun.com Exclusive: Read Chapter Two of Matt Centrowitz’s New Book “Like Father, Like Son”

by LetsRun.com

January 30, 2017

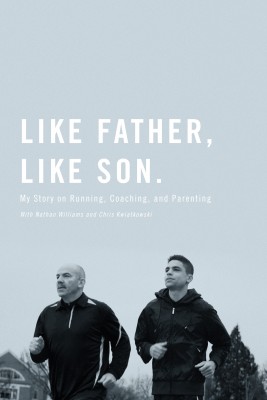

(Editor’s note: Matt Centrowitz, the two-time Olympian and former American record holder at 5000 who is perhaps best known these days for being the father of 2016 Olympic 1500 gold medallist Matthew Centrowitz, has self-published an autobiography about his life, his views on running, and the important role coaches and fathers play in people’s lives entitled Like Father, Like Son: My Story on Running, Coaching and Parenting. LetsRun.com co-founder Robert Johnson read a pre-publication edition of the book and loved it. His full review of the book, which he wholeheartedly recommends you buys, can be read at the following link: Legendary Athlete, Father and Coach Matt Centrowitz Just Published An Autobiography – We Suggest You Read It.

The book is now live on Amazon. So please purchase the book and read it. Then come back in a month and be a part of the first-ever LetsRun.com Virtual Book Club. To encourage you to read the book and thank you for supporting him, Centrowitz has agreed to do a podcast with LRC where LetsRunners can ask him questions they have after reading the book. We’ll do that at the end of February so get the book now to make sure you have time to read it before the podcast.

Available now on Amazon

Available now on Amazon

Centrowitz is pretty darn confident you’ll enjoy his book. Why do we say that? Because he’s letting LetsRun.com visitors read a whole chapter for free. In actuality, he said we could republish the first three chapters but we felt like it wasn’t right to give away that much of the book for free. So below, we’ve decided to publish chapter two, one of our favorites, which details how Centrowitz got involved with running.)

Note: The version below is a pre-publication version of chapter 2 so the actual chapter likely will have a few more edits to it)

CHAPTER TWO: THE BRONX

Reprinted with permission from Matt Centrowitz

Track saves people. I believe that. As a runner, a coach, and a father, I’ve seen it time and time again.

At the very least, it saved me.

In the summer of 1969 it felt like the world was falling apart. I’d say I finished eighth grade, but survived is more accurate. I flunked every class—every single class—and missed school over 50% of the time. My school, PS 22, was one of the worst in the Bronx, with one of the city’s highest truancy rates—and I was its best truant.

But it wasn’t just me. For generations the Bronx was a rock-solid, working-class neighborhood that had its share of wise guys, but it was mostly full working families, where mothers stayed home and fathers went to work in the nearby factories. But in 1969 it had started to spin apart. The families that were doing well got out, leaving only the families, like mine, that were struggling.

I don’t know what the reason was, or even if there was just one reason. Some say it was the newly built Cross Bronx Expressway that sliced old neighborhoods in half and turned the blocks on either side into slums. Some that it was the growth of the suburbs luring the higher income people out, and discriminatory redlining policies kept people of color from following. Others say it was the death of the Tammany machine that, despite the corruption and graft, kept the city running smoothly. The factories—that the Bronx was once famous for–closing left and right didn’t help either.

In any case, all I know is almost overnight the neighborhood got much poorer. And the Irish, Jewish, Polish, Italian, and German faces in the streets outside my flat suddenly became Puerto Rican ones. Even the president of the whole Borough of the Bronx—once the same Italian guy for almost 30 years—was Puerto Rican. As a kid, of course, I didn’t have any problem with all the new neighbors. They talked different, cooked different food, played different music. The neighborhood was full of unfamiliar smells and sounds. But they didn’t make the place poorer, they just came in because the rent was cheap.

White flight made the property values drop like crazy, so landlords started burning their own buildings to collect on the insurance. Sometimes tenants got a tip-off, sometimes they didn’t. The arson got so bad they eventually had to change the insurance laws. All the while the city was actually closing fire stations due to budget cuts. By the mid-70s parts of the south Bronx looked like a war zone—buildings turned to rubble and nothing built in their place. And in spite of all that, it was still my neighborhood, it was home, and I had to try to make it work for me.

The first day of junior high I wore a white shirt and tie, like I always did in elementary school, and I went in the boys’ bathroom. It was like a nightclub. Kids were smoking in there and drinking wine—early in the morning before class. So I took that tie off real quick and learned how to dress a lot different, and started transforming into a screw-up like everybody else.

So the only learning I did those years was in the streets with my friends. We drank, we smoked cigarettes, we smoked pot. I was in every kind of trouble there was. I was trying to be a big shot. We weren’t serious criminals by any means, but we were going nowhere fast. I was on my way to being a low level hoodlum, but plenty of guys around me were already hardened criminals.

One Thanksgiving weekend I was locked up in juvenile hall because they found marijuana in my locker. There were whole different kind of human beings in there. I saw really bad fights. I saw a guy get raped. It was terrifying stuff for a 13-year-old to witness. I realized then that I never wanted to go back. They labeled me a PINS: a Person in Need of Supervision, which is really what I was. Not a fundamentally bad kid, just someone who wanted to grow up too fast, be a man before I knew what being a man even was.

And then to make it even worse: my parents split up. It was always a difficult marriage. My mother, Theresa Corrigan, was a first-generation immigrant, sailing to New York from Ireland at the age of 15 and working as a maid most of her life. My father, Sid Centrowitz, was Jewish, and grew up in the Bowery in Manhattan and became a professional gambler. In a way, he was impressive. He was the only Jewish gambler allowed to run a card house in Little Italy in the West Bronx. And by all accounts he ran it well. They didn’t drink, didn’t mess around with any nonsense, they just kept the action going. Sometimes they’d stay up for 24 hours easy, three or four days with minimal sleep, just to keep people gambling. He was entertaining, he was funny. And he was good at getting people to lose their money. He worked for the mob, of course, and he would get a cut. And he would skim some money off the top.

And then to make it even worse: my parents split up. It was always a difficult marriage. My mother, Theresa Corrigan, was a first-generation immigrant, sailing to New York from Ireland at the age of 15 and working as a maid most of her life. My father, Sid Centrowitz, was Jewish, and grew up in the Bowery in Manhattan and became a professional gambler. In a way, he was impressive. He was the only Jewish gambler allowed to run a card house in Little Italy in the West Bronx. And by all accounts he ran it well. They didn’t drink, didn’t mess around with any nonsense, they just kept the action going. Sometimes they’d stay up for 24 hours easy, three or four days with minimal sleep, just to keep people gambling. He was entertaining, he was funny. And he was good at getting people to lose their money. He worked for the mob, of course, and he would get a cut. And he would skim some money off the top.

My father had a sick view on society. But it came with the era. Everyone had a vice – drinking, drugs, women– and my father chose to gamble. As with any addiction, there were massive highs and traumatic lows. He was extremely controlling. We had to eat exactly as much food as he put on the plate—no more, no less. When we rode in the car we all had permanent assigned seats. It was like the military.

One day, it became too much for my mother. Her doctor told her if she didn’t leave, she’d have a nervous breakdown. So, when I was nine, she left. And because the law at the time disallowed children of different genders to sleep in the same bedroom, she could only afford to take my sister Maureen. So for three years we only saw our mother on weekends. The upside was that my mother, who was a nervous wreck when she was with my father, became almost a totally different person. She understood the stresses we were under and became more of a friend in a lot of ways. So while I saw her less, she actually became a bigger part of my life.

For those three years my younger brother Gerald and I lived with my father—who only got worse after my mother left him—and waited for my mother to save enough money to afford a two-bedroom apartment. When that day finally came, my brother and I didn’t hesitate. We chose our mother. Instead of taking this like a man, my father cut us off. He decided he wanted nothing to do with us. And the last thing he said to me was, “You’ll never amount to anything without me.”

That’s about the worst you could ever say to a 12-year-old. I didn’t see him at all for the next seven years.

***

By 1969, sensing that I was headed down a path as bad as my father’s, my mother moved us out of the Bronx. She quit her job, went on welfare, and moved us out to Queens. Now Queens and the Bronx may look close on a map, especially if you’re not from New York, but to me it was a whole different world. It took two-and-a-half hours to get there using public transportation. For better or worse, I was leaving my old life entirely behind.

It may sound like there was nothing to miss about the Bronx, but that’s not exactly true. One great thing, maybe the best thing, about my old neighborhood is that we lived just two blocks away from Yankee Stadium. And in the 50s and 60s the Yankees were the absolute pinnacle of the sports world for the whole country. They were the best, most glamorous team in a sport that was then America’s undisputed pastime. And I got into games for free.

My older sister was a looker—or so they said—and to earn points with her the older boys in the neighborhood who worked the games would let us in for free (saving us the quarter a ticket would cost). We’d bring our own lunch and have to sit in the bleachers, but as the game wore on and the suit-and-tie crowd from Manhattan and the suburbs left early, we’d sneak down to the good seats. Nobody ever minded. It was kid-friendly in those days.

And I didn’t just love baseball, I loved what the Yankees represented. They were winners. Even in the rare years they weren’t winning the World Series (they won 8 between 1950 and 1962 alone) they were still Winners. Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris weren’t just great players, they were like aristocrats. The crowd wore white shirts and ties, the food was better, the stadium was better. It was a whole organization built on a self-reinforcing culture of winning.

My mother also loved baseball—she went to Yankee games pretty often and always religiously kept score on her score card. She even taught my brother and I to throw and catch. Even when he was still around, my father worked seven days a week, so we barely saw him—but my mom taught us a lot about baseball when we were younger. She was very athletic for a woman in those days—completely unlike my father who was fat and slow. Tall, always thin, with unusually big feet, she played street games with her brothers, and with us kids—and sometimes I wonder what kind of success she could have had if she had been born in a different era.

There was no Little League at that time in the Bronx. We’d either play stick ball or curb ball. Curb ball had all the rules of baseball but no batter or pitcher. Instead you had a Thrower who would throw the ball at the corner point on the curb and the ball would bounce back into the “field of play.” Fly ball could be caught out, ground ball you’d have to throw out. You run around the bases same as baseball. Depending on time of day it could get kind of hairy. Cars coming by. Sometimes they’d interfere–that was just bad luck. Sometimes a kid got hit by a car.

We played other games: touch football and sometimes sewer-to-sewer races. We raced by height, so because I was taller than average I was usually racing older kids. It didn’t mean that much to me then, but I won more than I lost.

The thing I later tried to drill into my own kids is that back then we organized ourselves. There was no higher authority to appeal to—you had to negotiate. The older kid told you the ball was out, you had two choices: you either hit him and got beat up, or you take your lumps and you look like a schmoe.

A bunch of guys who didn’t mind looking like schmoes were the New York Mets. Their first two years in 1962 and 1963 the Mets played in the old Polo Grounds that the New York Giants abandoned when they relocated to the West Coast along with the rival Dodgers. The corny Mets not only used another team’s stadium scraps, they took their colors too—combining the Giants’ orange with Dodger blue into a color combination that made them look like clowns. Even their own manager—former Yankee great Casey Stengel—seemed to think the whole thing was a joke. He cracked wise about his terrible players to the press, who ate it up.

The Polo Grounds were in upper Manhattan, a short walk from our apartment in the Bronx. But I rarely went. Not only was the product on the field a wreck, but the losing attitude extended to the crowd. No ties, that’s for sure. Most of the time they were drunk, falling down, fighting, you name it. They even drank a different beer—Rheingold instead of Yankee Stadium’s classier Shaefer Beer.

Pretty early on I could tell the difference between a winning environment and a losing one.

And guess where those Mets had moved in 1964? You got it: Queens. And here I was following in their footsteps. The crazy thing was, the year I moved, 1969, the “Miracle Mets” shocked the world—their own fans most of all—by winning the World Series. But that was in October, and when school started after Labor Day all I knew was that I wasn’t in the Bronx anymore. While the Bronx had what felt like a whole new population overnight, Queens had the same traditional mix of working class whites and blacks, but change was coming from within.

Our part of Queens was almost entirely black and for the first time I really saw signs of what had been going on throughout the country in the 60s. People were outside protesting in the street. Vietnam. Black power. There wasn’t anything resembling conformity. Anything that could be rebelled against, was. My mother enrolled me in Andrew Jackson High School, a school that had police officers stationed within the school. The school had proud traditions, but was caught up in the chaos of the times—in fact just a few years after I left, the police actually shut down a heroin factory that was operating in the basement of the school.

Kids weren’t just cutting classes here, they were in open revolt. Flipping a teacher’s car over outside. They’d be sucker punching people, even the teachers. I saw a teacher get beat up by students—that really opened my eyes.

So I really don’t know what would have happened to me if I hadn’t had the sense to listen up in gym class that first day.

“Track tryouts. Today. 3pm. See Coach Blatt out by the track.”

I thought, okay, this is something. Maybe I can do this.

I already knew I was fast. And that I liked running. We played games more than raced, but the older I got the more I won those sewer-to-sewer races. But for most of my life I had no idea competitive running even existed. A baseball player runs down the base path, a football player runs down the field, but a whole sport just dedicated to running? It was news to me. Then the 1968 Mexico City Olympics changed all that.

Track and field may have been unknown to young kids in the Bronx but on the world stage, in the Olympics, it was the centerpiece. The best athletes on earth competed for national pride at the height of the Cold War. The Yankees may have won the World Series, but it’s not like the Russians cared. Every country on earth wanted to win the 100m.

On my black and white TV I watched, riveted, event after event. 200m, 400m, 800m, 4x400m, 1500m, hurdles, steeplechase, marathon—I had no idea so many running events existed. It seemed like every country in the world was competing for these medals and the Americans were winning a bunch of them. In the 400, Americans cleaned up, taking home gold, silver, and bronze, with my new hero Lee Evans decimating the world record in 43.86 (which to this day still has him in the top ten fastest quarter-milers of all time). I consumed every minute of Olympic track and field, especially the events that the American’s were winning. You see, unlike today where we have hundreds of channels to watch on television, or the sites to visit on the internet, back in 1968, we only had one of three networks to watch. So, when something like the Olympics came on, everybody watched, especially kids like me looking for role models. During those games, track athletes like Bob Beamon, Jim Hines, Bill Toomey, Lee Evans and Tommie Smith, became household names. And Evans and Smith, because of their bold Black Power salute, became even bigger than that—they were icons (and, to some, villains).

I honestly didn’t understand the politics at the time, but when Evans anchored a 4×400 relay team that also blew away the world record—and the nearest competition by almost 50 meters – I was hooked. Running the lead leg on that blazingly fast relay team was a young guy named Vince Matthews. And where did Matthews—who would later win an individual 400m gold of his own in Munich 1972—come from? You guessed it: Andrew Jackson High School in Queens, New York.

So you could say the tryouts got my attention.

I learned that not only did Andrew Jackson produce Matthews, Coach Blatt had trained Julio Meade, who was then an All-American sprinter at Kansas, and Andrew Jackson had the standing national high school record for the 4×880, a record—7:35.6, set in 1966—that would stand for almost 25 years. Olympians? All-Americans? National records? I knew then that this Coach Blatt had to be a hell of a coach. I thought I was pretty fast—at least I could beat anyone my age in the sewer-to-sewer races in the Bronx—so maybe this coach could make something out of me? Sure didn’t have anything to lose by trying.

I showed up that afternoon in my beat up sneakers and cotton shorts and shirt that still smelled of sweat from gym class, ready to prove myself.

“Freshmen! Line up over here,” Blatt yelled. I drifted over to a corner of the track with maybe two or three-dozen other kids. As with the larger student body, I was one of the only white kids.

“No, kid, what are you doing?” I heard, as I was shuffling through the crowd. Somebody must have been goofing off. I looked around to see what the offender had been caught doing. Instead I saw the legendary Coach Milt Blatt staring dead at me.

“You,” he said, “You kidding me? You’re no freshman.”

At that point I was a big kid, at least for those days. 5’10”, 175 lbs. Most of it muscle. Compared to the skinny freshmen around me, I looked like a football player.

Sheepishly I protested, “I am, sir.”

“How old are you?”

“Fourteen.”

He shook his head. Clearly he didn’t believe me, but wasn’t going to waste any more time on some white kid who probably wouldn’t make the team. “If you’re still here tomorrow, bring a birth certificate.”

I nodded, hoping my mother hadn’t left my certificate back in the Bronx.

“Okay, first eight of you, line up. Take a lane. No horsing around.,” he said, walking back over to the finish line. “Hundred-yard dash. End of the straightaway here. Full sprint, okay? Run like men.”

A little humiliated at being called out on my size, I hung back and watched the first group go off at his starter’s pistol. He had his own stop watch and a clipboard, conferring with each of the kids at the end of each heat to get their names.

The sewer to sewer races we ran were about 25 or 30 yards. Sometimes we’d run two sewers at 50 or 60. Any more than that was basically guaranteeing a car or something would interfere and spoil the race. But this 100 on a flat straightaway seemed manageable. At least I wouldn’t have to keep an eye out of the corner of my eye for a cement truck.

Finally, at the third or fourth heat I lined up in the far outside lane, a stocky white kid next to all these lanky black and Dominican guys, and dug the bald rubber heel of my worn-out sneaker into the cinder track.

Crack! The starting pistol went off and I churned my legs. Did I think at that time I was bound for greatness? Not really. I just wanted to make the team. Just to have some kind of purpose. To be good at something, anything. And maybe to have somebody like Coach Blatt respect me. Whatever that was—hunger, desperation, hope—it pushed me.

I crossed the finish line a full stride ahead of all the other kids. Not even panting I jogged over to Coach Blatt.

“Name?”

“What was my time?” I asked, not even knowing then what a good time was.

He ignored my question. “Name?”

“Centrowitz, Matthew.”

Blatt didn’t even look up, writing my name in pencil on his clipboard.

“Okay, Centrowitz. Bring your birth certificate tomorrow.” And with that he turned to the next kid, “Name?”

So I was on the team.

Review: LRC Legendary Athlete, Father And Coach Matt Centrowitz Just Published An Autobiography – We Suggest You Read It

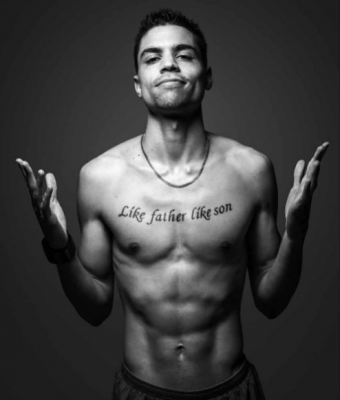

PS. The book opens and closes with this scene.

YOU WANT TO KNOW WHAT THE OLYMPICS IS ABOUT. THIS IS WHAT IT IS!! pic.twitter.com/sCz46zSd7n

— Leslie Jones ? (@Lesdoggg) August 21, 2016

Get Notified of the Centro Podcast

[gravityform id=”479″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”true”]

Note: LetsRun.com gets a commission from amazon if you buy products through our links. So buy the book and a bunch of other stuff too 😉