An Oral History Of The 2012 Olympic Trials Women’s 5,000, Part III: The Aftermath

By Jonathan Gault

June 29, 2016

No meet captures the imagination of American track & field fans like the US Olympic Trials. And at the 2012 US Olympic Trials, no distance race was more dramatic than the women’s 5,000 final (LRC The Women’s 5,000 Final – The Olympic Trials At Its Absolute Best: The Battle For Third Is One That Will Not Be Forgotten).

It had everything: absolute elation and devastation; an unlikely victor upsetting one of America’s greats; a bold late-race move; a young star breaking onto the national scene for the first time; an epic three-way sprint for the final Olympic spot; and redemption stories galore. It was everything that is great about our sport, years of pain and sacrifice distilled into pure joy for the three Olympians and utter disappointment for the woman who came four-hundredths of a second short of her Olympic dream.

But this was more than a race. The fans saw 15 minutes of racing on the track, the victory laps and the post-race interviews. They didn’t witness the obstacles these athletes had to overcome to even make it to the starting line. Nor did they see what came in the days, months and years after, the struggle to return to normal following the highest high or lowest low of an athlete’s life.

With the 2016 Olympic Trials set to start on Friday, we revisit the story, as told by the women who made it. Part I, published on Monday, gives the backstories of the main players and recounts their roads to the Trials. Part II, deals with the race itself. Part III below deals with the lasting effects of the race on the women who ran it. Portions of the following interviews have been condensed for clarity.

If you missed Part I, click here to read it.

If you missed Part II, click here to read it.

***

After the Race

Julia Lucas: I sat down on the track and my teammate Lauren Fleshman came by and touched my shoulder and I was like basically, “Do not touch me.” It was too big of a moment to absorb and as a human to fit in my head.

Abbey D’Agostino: I think [my feeling right after the race] was shock. Kind of confusion, just a surreal experience. I wasn’t really emotional until being interviewed after. I remember trying to go congratulate Kim, trying to get her attention and she just was not having it. Of course, she was in the moment. I don’t think I realized how special that minute is post-finish until later.

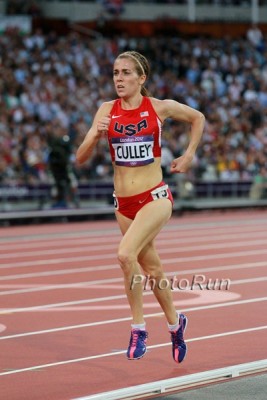

Julie Culley, Molly Huddle and Kim Conley soon took the ceremonial victory lap. For Culley, two moments stood out: seeing her college coach, and seeing an Oregon legend.

Julie Culley: Being a [Matt] Centrowitz [coached] athlete in the early stages of me coming back, any time we competed at Oregon it was always really special because Coach would take us to Bill Dellinger’s house. I had been at Bill’s house the day prior. I just remember looking through all of his scrapbooks, him winning the bronze medal [at the 1964 Olympics]. Someone called my name and they said “Julie, look! Look here!” And they pointed and Bill got up from his seat and gave me a big fist. He was so happy. He had tears in his eyes and he was pumping his fist for me. It was this really cool moment for me because of this connection to the history of that venue and having someone who’s so storied and so famed at Oregon to be sharing this moment with you.

Julie Culley: Being a [Matt] Centrowitz [coached] athlete in the early stages of me coming back, any time we competed at Oregon it was always really special because Coach would take us to Bill Dellinger’s house. I had been at Bill’s house the day prior. I just remember looking through all of his scrapbooks, him winning the bronze medal [at the 1964 Olympics]. Someone called my name and they said “Julie, look! Look here!” And they pointed and Bill got up from his seat and gave me a big fist. He was so happy. He had tears in his eyes and he was pumping his fist for me. It was this really cool moment for me because of this connection to the history of that venue and having someone who’s so storied and so famed at Oregon to be sharing this moment with you.

While his wife had just missed out on the Olympic team in the most agonizing fashion imaginable, Ian Dobson still had his own race to run: the men’s 5,000 final.

Ian Dobson: Obviously it wasn’t fun, but I was not looking forward to my race all that much anyway. I knew I was in shape to run like 13:30, which was not going to make me very competitive. I don’t think [Julia’s race] had an impact on my performance because my performance wasn’t going to be anything to look back on anyway.

Dobson wound up 14th of 16, running 13:51, 29 seconds behind winner Galen Rupp.

Lucas: I headed through the interview tent, did my interviews.

Lucas’ post-race interview was as classy as it gets. She answered every question, laid bare her faults and admitted “I gave that race away.”

Dobson: I think that Julia’s post-race interview was just in some ways sort of sterile because she took some emotion out of it. But I just respect the hell out of Julia for how she ran that race and how she handled herself in that interview.

Lucas: After I was in the fire [in college], I was interviewed by police because it turned out to be arson. I gave very clear answers and was really composed. And they had me listen to my own 911 tape, which included me screaming as I ran through the fire and they later determined that my answers were unreliable because I was in clinical shock. I think this was actually a really similar case. I don’t know if I deserve that much credit for being composed. It was too much to absorb and my emotions left me. I don’t know how much I trust my answers. I don’t know if the version to believe is what I remember now or what I remember[ed] after the race.

D’Agostino, only 20 years old at the time, was trying to deal with a tidal wave of emotion after the race. That wave hit in the mixed zone.

D’Agostino: I remember being interviewed and hitting a nerve while I was still processing [what was going on]. I remember Lauren Fleshman coming up and comforting me. She was very thoughtful and kind, bringing me back to earth in that moment.

It hurts more in a way to be that close. It’s a common experience. I’m very aware of how ungrateful of how that sounds, but it’s hard to be in that moment and just miss it.

Lucas: I sat in the drug testing room afterwards waiting to pee. The three Olympians were there and I was also there and honestly, that didn’t make it worse, it just made it funny. Like how bad could this day get?

Dobson: I remember everything just being a long, tedious slog. [At] the time, there was some small sense of humor about it like, “Man, this sucks.” You just have to shake your head a little bit. As you may know, Julia and I are no longer together. Our relationship was in a tough spot at that point and I think we did a good job compartmentalizing it. But I was not going to be the person who was going to be her big support [after the race] whether I wanted to or not.

Lucas: I maybe was in there for 45 minutes. Molly walked past me and touched my shoulder and said “Tough race.” Which is the thing to do — there’s nothing to say. She was a wise and empathetic human in that moment. Julie ran out of her mind and was basically in the position I was in terms of coming from nowhere and surprising yourself. And she touched my shoulder and said, “Aw I’m sorry.” And I was [thinking] like, “I hate you, I want to pull your tongue out of your throat and bash your skull against my knee, I hate you.”

And Kim Conley, who was in an even more coming from nowhere position and whose story bucked up against mine — you don’t mention one of our names without the others in regard to the Trials though she’s of course gone on and ran spectacularly in her own right — she just walked away from me and wouldn’t make eye contact.

Culley: Drug testing was the first time we saw Julia. That was really hard. I can’t imagine what that moment feels like. That moment of jubilation is not something you want to rub in someone’s face. It was just the four of us. You could hear a pin drop. I’m sure anything we would have said at that point would have just been meaningless.

Lucas: I saw my parents and my college coach. And then I left them, went on my bike, still sweaty, to the river by the stadium, which is a thinking place I guess. I sat there for a good hour and drew in the mud, collected myself and then got raging drunk with all the people who were in town for the Trials. I had a great time that night. [Missing out] was [still] too much to process.

Culley: What do you do after you make the Olympic team? You go out and party! So we went out and had a great time.

London and the Summer of 2012

Culley, Huddle and Conley went to London and competed well. Culley (15:05.38) and Conley (15:14.48) both PR’d in the prelims. Huddle and Culley made the final, placing 11th and 14th, respectively. But neither Culley nor Conley were satisfied.

Kim Conley: I was pretty disappointed not to make the final. But I think that turned quickly into a fire and a hunger and an eagerness. The years between 2008 and 2012, I had not spent in any way preparing for the London Olympics. Really getting to the Trials was my big dream and then as we got closer into 2012, making the Olympic team became the dream. Coming out of London, I started to realize that now I’m going to think in terms of Olympic cycles and trying to get back to Rio a much more competitive athlete and someone who would make the final.

Culley: It’s easy to say, “Hey, she PR’d in the prelim, she wasn’t going to have anything left for the final.” But that PR, my fitness was so on point that that PR didn’t feel like a PR. I didn’t know that I ran that fast. When I saw the time come up, I was like “What? No way.” That didn’t feel hard.

I was so pumped for that final but looming in the background was this hamstring injury. That hamstring thing was real and it just finally hit a head. These championship races are gonna go out really, really slow and then there’s going to be a moment where the pace just flips and you’ve got to commit to it. The moment the pace flipped, I tried to open my stride, I tried react to it but I had nothing. The power in the left side of my body was gone.

Lauren Fleshman: The Olympics can never live up to the expectation that we make for it. Unless you go to the Olympics and win the gold medal and set a WR, you’re gonna go home with some sort of disappointment. I’d love to see a satisfied Olympian. Athletes always want more.

The one silver lining? Culley made history for a legend of the sport.

Frank Gagliano: She is the first athlete in my 55 years that ran in the Olympic final. Fantastic. A young lady from Clinton, N.J., Rutgers University, [running against] the best in the world. Unbelievable. She’s just a tremendous person. I really, really enjoyed coaching her and her friendship.

Lucas watched the replay of the Trials race for the first time later that summer as a speaker at Rollie Geiger’s All American Cross Country Camp.

Lucas: I saw it on the big screen in the first row and then gave my talk. I never cried or anything but was kind of knocked over like, “That was a thing that definitely happened.” If I was going to lose an Olympics spot, I’m really glad I lost it like that. At the same time, I really wanted to be an Olympian. It’s a sad ending for me.

Lucas received a lot of public support after the race.

Lucas: After the race, a number of people came up to me and talked about me running brave and how that touched them or running scared or confidently for the win or [how they thought I ran in a] terrified and confused [manner] and how that touched them. The people who are going to say, “man I went too early, I messed up” don’t say it to my face.

I don’t regularly read message boards but there was a message board thread about me that someone else told me about and I was like, “I’m going to read that entire thread.” And I did that. (Editor’s note: We assume it was this one: MB: Official Julia Lucas Appreciation Thread!!!)

Instead of London, D’Agostino spent the rest of the summer training with her college teammates in Hanover, N.H.

D’Agostino: I don’t think I harped on it to an unhealthy extent. To be honest, I was young, so I was going back to school for sophomore summer. There was a lot to look forward to in the next few months but also the next couple years knowing that the standard was a little bit higher now and that I had room to grow. I think that’s what allowed me to move on and detach from the disappointment.

It definitely took a while, probably several days after hearing from people and talking to family and friends and others in the sport [to realize how special the race was]. I’ve never been a track junkie. I knew some of the big names, had some idols in the sport, but I kind of lived under a rock when it came to momentous things like that in sport in general. It took some time to fully understand it.

Jackie Areson’s shocking failure to make the final in Eugene stuck with her for the rest of the summer.

Jackie Areson: I tried to push through and race after that race but I just couldn’t do it. Just mentally, I couldn’t get through runs without crying. It sounds bad, but the only way I could get through a run was just hammering. It was the only way I could force myself to not cry. So I just said what’s the point in doing this, I just need a long break.

***

Moving On

For some, that night in Eugene was merely a stepping stone to future greatness. Molly Huddle emerged as America’s greatest distance runner on the track. Kim Conley won a U.S. title at 10,000 meters in 2014. Abbey D’Agostino made the World Championships in 2015. But for others, that race changed their lives forever.

D’Agostino: It was a gift in that I was able to recognize and believe the fact that I was capable of competing well at that level. I had competed well before, but not on a stage like that.

Conley: Immediately after in 2012, when I was still in Eugene, I think I watched it every day for a few days. Now [I] hardly ever [watch the race]. It’s really [only] if I’m doing an appearance or something and they play the video.

It completely expanded my horizons and changed my baseline expectation for myself. In 2012, I got third and it was this huge dream come true. By 2013, when I got fourth at USAs, that was a big disappointment. Because I got third the year before, that became the minimum expectation that I had for myself.

I think at this point in my career, I feel like there have been other career highlights. [That race] is certainly part of the story and right now, that’s the big moment where I arrived on the scene. But we don’t know what the future holds. Maybe there’s another great exciting moment ahead.

Wartenberg: At any level, whether it’s a state meet or NCAAs [or pros], you can create a moment that will change your life and change your career. And I think that was one of those moments. Kim was doing well in 2012 but her goal was to be good enough in 2016 to make a team. 2012 was not part of the written plan.

When it happens, it definitely — in a good way — turns your world upside down a little and it opened doors in terms of sponsorship and relevance on an international stage. But the last four years have been about not living off that moment. And I semi-seriously said hopefully we’ll never have to make a moment like that again. It’s too hard to coach through those! Maybe a vanilla moment might be easier. But I don’t think Kim would trade that moment for being a lock on the team or for being someone who simply went through the motions that year to make the team.

D’Agostino: I very much feel now that I’ve detached from 2012 and that experience. What motivates me is deeper. I just feel so powerfully that this is my calling. I’ve been given the ability and the tools and the people around me necessary to compete and it’s just a chance to glorify God through that opportunity and be grateful to it and totally surrender the results.

My validity as a human doesn’t depend on the results but it’s really easy to perceive the Trials that way. Four years. It’s a four-year buildup. And everyone feels that pressure right now.

But the World Championships are a big deal. The caliber of the competition is the exact same essentially. It’s really interesting and I haven’t thought deeply about this, but on a systemic level, we place more emphasis on the Olympics despite the reality that the competition is the same. Though I do think that the Olympics are unique in that they’re a celebration of athleticism and the peak of athletic success across sports and it’s a global celebration of that.

Fleshman: The fact of the matter is, I don’t care about the Olympics the way I used to. I feel like it’s kind of overblown and I think by worshiping the Olympics, we really minimize what athletes do on a day-to-day basis and all the other competitions and things that really contribute to the health and sustainability of the sport every day of the year.

My biggest fear was not making the Olympics for a long time. And I didn’t make the Olympics and everything’s fine. In fact, it’s more than fine. You don’t always get what you want. More athletes don’t get what they want than get what they want. I’ve had a really great career and no complaints.

I know enough people who have made the Olympics that it doesn’t really change your life. We want to think it does and that’s what drives you so hard to do it, but the fact of the matter is that it doesn’t change your life. You can be from some countries and make the Olympics and not even have the standard. The year I missed it by one spot, I could have made the Olympic team in all countries in the world except for maybe three. Why would you ever put your stock as an athlete or person or ultimately let that determine whether you’ve had a successful career or not when it’s that arbitrary?

The right people make the team on the day. You don’t deserve anything. And I had that mindset for a long time of feeling like things just weren’t working out for me in Olympic years so somehow I would be more deserving the next time I had a chance than other people. And that’s bullshit. You don’t deserve anything.

Lucas: To add a note to your to resume or at you’re at a dinner party like, “Oh I’m an Olympian, are you an Olympian?” That is a stamp of legitimacy, absolutely, but I think most Olympians would agree with me in saying that’s not going to be the “it.” That can’t be the “it” for your career.

Areson: I moved to Houston after [the 2012 Trials]. I think I was able to move on from it, but I don’t know if I ever got over it. I still don’t live with it that well. People who don’t know you, they’re like, “Oh you’re a runner? What level, the Olympics?” [sighs] and it’s just still so hard for me to think about. When you tell them you’re not an Olympian, people shut off and that’s really hard for me. I want to say, “I was really close, but I blew it.” But I don’t, obviously. I have some Pan Ams gear that I wear occasionally with the Olympics rings [on it]. And people are like, “Oh, did you run at the Olympics?”And I’m like, “[sigh] I don’t want to talk about this.”

Culley: The one thing I learned about that whole buildup was that believing that you can do something is really all-encompassing. It’s not something that you wake up one day and are like, “Oh yeah, that’s my goal.” Something I really learned about myself through that process — deciding I was good enough to make that team and embracing that — it’s something that you live and breathe every day. It’s not something you forget about, it’s not something you work on a practice, or out on a run. And I don’t think I really understood that prior to 2012. The emotional connection, the commitment that you make was something so much bigger than anything I had ever done before.

It’s so easy to have a goal, but really truly taking that on and being vulnerable to that one goal, that was what was so scary about that race. I had never ever put everything into one basket. I had always had these safety nets around me like, “If it doesn’t work out, at least I did this. If it doesn’t work out, at least I’m a well-rounded human being.” When you want to make an Olympic team and you want it so badly and you’re not clear-cut the most talented, there’s a different edge that you have to have. That’s not something that I’ve really experienced since then. Something I’m more proud of in myself, almost more than winning or making the team was embracing that that was my goal and being vulnerable to it.

I think I wasted all of my emotional energy for my lifetime in 2012. I came off of 2012 and just felt that I was the athlete that I had always dreamed of being. I crashed really hard. And I wasn’t expecting that, but I ended up with pretty severe adrenal fatigue and had to take some downtime to allow my body to recover kind of naturally from it.

When you’re kind of removed from it or you’re injured, it’s still so fun to think about how cool that was and remember that wasn’t just a dream, it was a really big part of my life.

Lucas: [Before the 2012 Trials], I was a real snob about the sport. If someone wasn’t breaking 16:00 in the 5k, I thought they weren’t any good at all. I kind of turned my nose up at someone who was doing it in a recreational or even in a very serious, but not what I considered national-caliber, way. In the two years that followed, I was a much more empathetic human. I think I’m a different and smarter and better human [now but] those years were really, really difficult times. There were moments where I didn’t handle myself well, I didn’t like myself. I used every coping mechanism that you can think of. I saw myself being a person I was ashamed to be.

I think it took a year to sink in and in that time, I was not the self that I was used to. I wasn’t this go get ’em girl. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking to myself why that was. In total honesty, I think that the reason that I loved the sport was something more to do with a narrative and with meaning. I’m very competitive, I want to be the best in the world, but it was very important the way in which I was. I love dwelling on the allegories in the sport and the literary side of things. That race just had the biggest impact that I was capable of having in the sport.

I faked it for two more years. By faked it, I mean worked really hard, went to practice every day, ran 4:05 the next year [for 1500]. But I couldn’t tell myself the same stories as I did before. As soon as it was done, that night I was talking about coming back. In the interview afterwards, I said something about that, like you know, “I’m in it, I’m not giving up, I’m not a quitter.” I believe in creating your own story and I believe in muscling things into reality but I also believe in a “truth.” I’m not really a hippie [but] that story was never quite real to me. I feel like I was forcing it into being and it’s not the story.

If I had fought back and made it this time, basically what Kim Conley is doing right now, I don’t think that I was capable of reaching a mountaintop of meaning and impact that would have matched that low [of the 2012 Trials]. And I want meaning and impact. Other people say, “I don’t care what other people think, I’m doing it for me.” I can’t understand those people. I’m doing it for a connection, seeing humanity on the track, seeing something that’s inspiring. Running itself is totally purposeless — if you’re just turning yourself in a machine, well you could run faster than you ever could. I felt like my ultimate stamp on the world in the distance running world, I just felt like I had done it.

Julie Culley, 34, has battled a series of injuries over the past few years, racing just once since May 2014. She serves as an assistant coach at Georgetown University. Culley is currently seven months pregnant and expecting her first child.

Molly Huddle, 31, broke the American record again in 2014 and won U.S. titles on the track in 2014 and 2015. An early celebration cost her a bronze medal at the 2015 World Championships in the 10,000. She is a heavy favorite to make her second Olympic team this week at 10,000 meters.

Kim Conley, 30, won her first U.S. title in her hometown of Sacramento in 2014. She married Drew Wartenburg in 2015. Conley is entered in both the 5,000 and 10,000 at the upcoming 2016 Olympic Trials.

Julia Lucas, 32, stopped competing after 2013 and moved to New York, where she works as a speaker, coach and “a total freelancer for anything that involves running in New York City.” Her Instagram account is a constant source of inspiration. She separated from Ian Dobson in 2012.

Abbey D’Agostino, 24, graduated from Dartmouth in 2014 and now lives in Boston, where she continues to train under Mark Coogan. She made her first U.S. team last year at 5,000 meters and followed that up by making the World Indoor team at 3,000 in March. D’Agostino will run the 5,000 next week at the 2016 Olympic Trials.

Lauren Fleshman, 34, has not raced since July 2014 due to a nagging Achilles injury. She is the co-founder of Picky Bars and coaches the Little Wing group in Bend, Ore.

Jackie Areson, 28, switched nationalities to Australia in 2013 and made the World Championship final at 5,000 meters. After battling overtraining and undergoing surgery to fix a hole in her heart last year, she no longer runs competitively. Areson now lives in Sydney and begins grad school next month, where she is pursuing a masters in biotechnology.