“Out of Thin Air” Book Excerpt: Why “Idil” Is More Important Than Talent For Amhara Ethiopian Runners

By Michael Crawley

January 12, 2021

Five years ago, Michael Crawley, who has competed internationally for Scotland and Great Britain and owns personal bests of 30:07/66:13/2:20:53, headed to Ethiopia to spend 15 months living and training with some of the country’s up-and-coming runners. But Crawley was not there on a training trip. Instead, he was there to document Ethiopian running culture as part of his PhD project at the University of Edinburgh; training as an aspiring professional was his way of embedding himself.

Now Crawley has written a book, Out of Thin Air (LRC review here), detailing his time in Ethiopia, from 3 a.m. runs through the empty streets of Addis Ababa to altitude training at over 10,000 feet in the rural highlands. Below is an excerpt, in which Crawley discusses the realities of pursuing a running career in Ethiopia, and why the runners he met — including a young athlete named Tilahun — often don’t believe in the idea of “talent.”

***

While there is often a romanticized view of runners from Ethiopia and Kenya — of children striding to school barefoot across high-altitude plateaus and of people “running away from poverty” — Dr. Benoit Gaudin, a professor at Addis Ababa University and my host for my first few weeks here, is keen to emphasize that it is not the poorest of the poor who become runners in Ethiopia.

“The runners have to have some sort of support from their family,” he tells me, “and they need to have the time and energy to train.”

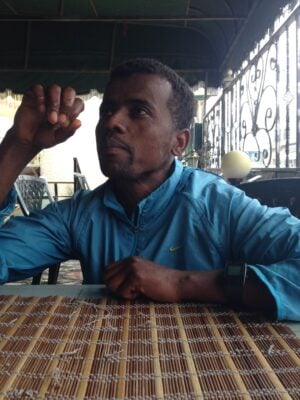

This is something that is brought home to me on one walk back from the forest with Tilahun. We are joined by a portly man swinging a briefcase on his way to work, who (conveniently for me) asks Tilahun what it takes to be a runner. Tilahun ticks off the ingredients for running success as he sees them on his fingers. First, you need gize — time. For running, but mostly for ireft — rest between training sessions. Second, you need good quality food in sufficient quantities to sustain training. And third, you need ya sport masariya. This is translated either as “sports materials” or “facilities”: running shoes and running kit, but also the bus fare to access preferable training locations around the city. You have to be able to access the beneficial training environments Tilahun spoke about on my first morning run and this could be an insurmountable expense for some.

Far from the media portrayal of East African athletes — of success because of a lack of shoes and because of hardship — these requirements actually represent a significant barrier to entry. They also represent a very significant investment and sacrifice — of education, of working opportunities and even of marriage. At this early stage of my research I didn’t fully understand this, though.

“I guess it’s not the end of the world if it doesn’t work out for someone like Tilahun,” I say to Benoit. “He can always go back to the farm.”

Benoit shakes his head.

“No. How do you find a wife if you’re 25 and a loser? The runners believe that they have something inside of them, so if they fail what does that mean?”

This idea of having something inside of you, a latent potential that needs only to be unleashed, is something that I have a faint notion of from reading a classic study of the Amhara, the ethnic group of the runners I would be living and training with. Most of the top runners in Ethiopia are from the Amhara or Oromia regions, with a smaller number from Tigray in the north. Because of the way training groups are formed from personal connections, though, the group I trained in were almost all Amhara. In Wax and Gold, Donald Levine writes of the Amhara notion of idil, which translates roughly as “chance.” Amhara Orthodox Christians believe their idil to be a kind of interior state of being about which only God has truly privileged knowledge. This means they believe that if they work hard and virtuously, they may be rewarded with performances that are truly transcendent and spectacular.

It also means that Ethiopian runners wear their ambition lightly. Even if they might privately have a fairly self-aggrandizing view of their own possibilities, to express this would be incompatible with the kind of virtuous life that must be lived in order to be rewarded. Not wanting to express pride in personal achievements explains why when confronted with a microphone in a post-race interview and the question, “How do you feel after winning the race?” even the more famous and well-travelled Ethiopian athletes will often seem reticent.

The belief in idil — that is, the belief that if you act in a certain way anyone may be raised to a position of greatness — also means that there is little in the way of belief in innate athletic talent or genetic ability in Ethiopia. Tilahun talks about only needing to “modify” his times. He adds, “I have two legs, you know, just like the others,” before patting them as if to reassure himself. When he tells me at one point that if I stay in Ethiopia for a year and do everything right I could run a 2:08 marathon I laugh, but I don’t think he is joking.

Throughout my time in Ethiopia, in fact, I never heard anyone mention “talent” or “natural ability.” Runners use the word lememed to refer to training as a runner, which literally means “adaptation” or getting used to something. Runners are either good at managing the process of adaptation or they are not. A good runner is most likely to be described as gobez, which means some kind of combination of cleverness and cunning, denoting an ability to plan and manage their training well. As Meseret, a local coach, frequently puts it to the runners, “You can be changed.” The implication here is a strong belief in the inherent malleability of bodies provided that runners conduct themselves in a certain way. I am often told how bad I am at managing this process of adaptation, insisting as I do on writing during the day, walking around to do interviews and otherwise refusing to allow my body to “adapt” to the training load. One implication of this belief is that an inability to “adapt” is often seen as the problem of the individual, as a moral failing of some kind or simply a result of not “working” hard enough. It is never ascribed merely to not having the “natural talent” to do so, which is how I (and I suspect most sports scientists) would explain my inability to run a marathon in 2:08.

Purchase the book and support LRC here.

You can read LetsRun.com’s review of Out of Thin Air here: “Out of Thin Air” Book Review: A Deep Look Into Ethiopian Running Culture Despite producing 42 of the 100 fastest men’s marathoners of all time and distance legends like Kenenisa Bekele and Haile Gebrselassie, few English-speaking writers have truly explored Ethiopian running culture. Michael Crawley changes that with his new book. 5 stars out of 5.