In Christian Coleman Case, Track & Field Cannot Win

No matter how this ends, somebody is going to be unhappy

By Jonathan Gault

June 19, 2020

Following the sport of track & field requires one to deal with doubt. Cynics embrace it. Optimists try to ignore it. Realists grapple with it. But it’s always there. It has been for decades — how can it not be in a sport where anyone with a brain can point to multiple world records set by obvious drug cheats that have been allowed to stand for decades?

It is a sad but inescapable fact that if you run too fast or jump too high, you will become the subject of doping speculation. Fans have been burned too many times that some have lost the capacity to believe.

9.80 seconds in the men’s 100 meters is one of those “too fast” times. Let’s be clear: we should not assume guilt solely because of an arbitrary time; it is not fair to the athlete. Someone can run 9.85 or 9.81, but 9.79 means they must be cheating? It doesn’t make sense. Still, of the 11 men in history to have run 9.80 or faster, nine have been handed a suspension for an anti-doping rule violation at some point in their career. One more, Maurice Greene, was never banned but was alleged to have paid for steroids (an allegation Greene denied). Only Usain Bolt — the fastest of them all — has never been suspended for an anti-doping rules violation or linked to doping.

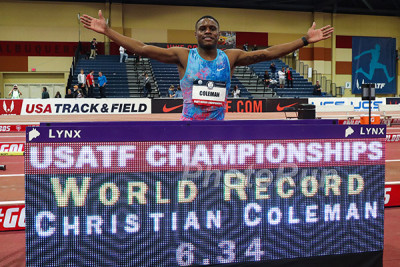

And into this environment strides Christian Coleman, the 24-year-old reigning 100-meter world champion and 6th-fastest man in history with his 9.76 personal best. Coleman once again is at the center of controversy after the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU) announced Wednesday it had provisionally suspended him for not being available to take three drug tests during the last 12 months — (for a full explainer of his three whereabouts failures, click here: LRC World’s Fastest Man May Face An Olympic Ban For Missing Yet Another Drug Test).

Some important facts: Coleman has never failed a test; he has denied doping, vehemently and repeatedly — in fact, he says he does not take supplements of any kind; there is no evidence tying Coleman to any sort of illicit substance. He has been open and offered clear explanations for each of his whereabouts failures. These facts are not enough to prove Coleman does not dope (as with every athlete, that is impossible to definitively know) but they must be stated.

But this latest debate is not about whether Coleman doped. Instead, we’re talking about whether the world’s fastest man was serious enough about his commitment to clean sport.

Because of track & field’s checkered past, with former Olympic champions like Ben Johnson, Marion Jones, and Jemima Sumgong all being banned for doping– many in the sport take their commitment to clean sport very seriously. Providing a location where you will be for one hour every single day of the year so you can be available for daily drug testing is incredibly inconvenient. Allowing a stranger to draw your blood and watch you pee is not fun. But both are necessary to preserve what credibility the sport still has.

So when Coleman, in his explanation about his latest whereabouts failure on Tuesday, wrote, “I am willing to take a drug test EVERY single day for the rest of my career for all I care to prove my innocence,” many quickly pointed out the irony.

“Proving your innocence is the very reason athletes follow the whereabouts and testing rules which he has repeatedly violated!” tweeted track & field legend Michael Johnson.

Remember, Coleman last year narrowly avoided a suspension after being unavailable for a drug test three times in a 12-month span. But one of the unsuccessful test attempts began one minute after the one-hour window he had provided for testing that day, which meant, thanks to a technicality, the failure was backdated to the beginning of the quarter. Normally, three whereabouts failures in 12 months triggers a suspension, but because that test attempt was (correctly, according to the rules) backdated, it fell outside the 12-month window, allowing Coleman a reprieve.

Coleman may have retained his eligibility through that ordeal, but his reputation took a hit. The cynical view: anyone with as much at stake as Coleman — the Olympic 100m favorite with one of the richest contracts in the sport — would only miss three tests if they had something to hide. The more charitable view: Coleman was careless with his whereabouts information. All three whereabouts failures, he said, came because he forgot to update his location, not because he was purposefully avoiding a test. After winning his World title in Doha last year, Coleman told the world he planned on becoming more diligent with his whereabouts information.

But as a result of the events of 2019, in the eyes of some people, Coleman lost any benefit of the doubt moving forward. After Doha, the entire world knew Coleman was sitting on two missed tests. For Coleman to admit he was not at home during a portion of his one-hour window for his most recent missed test on December 9 — even if he was only five minutes away, even if previous testers had called when they could not locate him, even if Coleman returned before the end of the window — was proof he was still not taking the testing system seriously enough.

“Last year you got off for the same sanction,” tweeted 2011 400m hurdles world champion Dai Greene. “To let it happen to you again is astounding. Being at your hour slot each day is a small price to pay for the life this sport has given to you and to help fight for an equal playing field for all athletes. Regardless of whether you are doping or not, the rules are there for the greater good of the sport. Being the best in the world means that you should be leading the way by example. Try treating the sport, your full time profession, and fellow athletes with respect they deserve.”

Other pros, however, are still sympathetic to Coleman.

“My heart, my energy, everything in me goes out to Christian Coleman,” 110m hurdles world champion Grant Holloway told the FloTrack Podcast on Thursday. “We all are human…It’s been plenty of times where my window says 9:00 and I was out to eat with either friends, family. I haven’t been exactly where my whereabouts said and I have lucked up and they haven’t came and drug-tested me. If all the facts line up with Christian and they say what they say, I don’t think Christian should be penalized.”

The AIU and the global anti-doping system is not beyond reproach here, either.

One of Coleman’s defenses for his most recent missed test is that the doping control officer (DCO) did not attempt to call him once he failed to locate Coleman — part of what Coleman alleges was a “purposeful attempt to get me to miss a test.” That excuse will not stand up in court — DCOs are not required to call athletes, and an AIU spokesman told LetsRun.com “the lack of any telephone call does not give the athlete a defense to the assertion of a missed test.” But Coleman’s revelation that he had received a phone call “literally every other time I’ve been tested” shocked several athletes; in many parts of the world, it is uncommon for a DCO to call an athlete under any circumstances.

“I find it mental that athletes in the USA expect a heads up for a random doping test,” tweeted Irish sprinter Leon Reid.

Then there are athletes such as Asbel Kiprop, who have been notified of tests well ahead of time (though in Kiprop’s case, he still failed the test). The point: athletes around the world are held to different standards when it comes to testing — the entire point of which is to ensure a level playing field.

More specifically, in Coleman’s case, he says the address the DCO listed for the test location in his report was not his own; “two or three words” were messed up. At best, that is negligent behavior for someone dealing with an athlete whose livelihood is at stake. If the DCO genuinely showed up to the wrong address, that’s a much bigger problem.

And Coleman is not the only athlete with a bone to pick with the AIU when it comes to the whereabouts system. US sprinter Gabby Thomas, whose provisional suspension was announced last month, is currently appealing her ban; she says her DCO never knocked on her door for her third whereabouts failure.

Overall, the AIU has announced significantly more suspensions for whereabouts violations in 2020 — eight in the first six months alone compared to a total of two in all of 2018 and 2019 combined. That raises a natural question: are violations increasing because the AIU is doing its job better — or because it is trying to ban more athletes, justified or not?

***

What happens next in the Coleman case is unclear. He’s been handed a provisional suspension and is expected to appeal; whether he is cleared will come down to Coleman’s word (he claims he was home before the end of his one-hour window) against the DCO’s (he claims he was at Coleman’s residence for the entire window and still could not locate him). And if Coleman is banned, the question is for how long? Three whereabouts failures carries a ban of two years, but under the WADA Code, it can be reduced to one year “depending on the athlete’s degree of fault.” 2016 Olympic 100m hurdles champion Brianna Rollins successfully lobbied her ban down to one year when she recorded three whereabouts failures in 2016. Should Coleman do the same, he could return to competition in time for next year’s Olympics.

No matter what happens from here on with Coleman, however, the sport of track & field cannot win. If his suspension is overturned, some will argue one of the sport’s biggest stars has been let off because of selective enforcement of the rules.

“If Coleman is allowed to race at the Olympic Games in 2021 it will set an absolute terrible precedent by our governing bodies,” tweeted German-American distance runner Sam Parsons of Tinman Elite. “It will open the flood gates for others to successfully cheat the system and ruin the credibility of our sport as we know it.”

Conversely, if Coleman is banned for the full two years and forced to miss the Olympics, track & field will be without one of its brightest stars — one who has never been linked to actual doping — on its biggest stage, possibly because he was not diligent enough about filing and adhering to his paperwork.

A one-year ban might offer the best middle ground, but it’s still unsatisfying. A one-year ban in a year without track is a toothless sanction; no one who wants to see Coleman face the consequences of his actions will be happy. Coleman, meanwhile, will get to compete in Tokyo. But the damage to his reputation will only intensify, and he’ll become the latest member of the sub-9.80 club to have served a ban for an anti-doping rule violation. No matter the outcome, even Coleman acknowledges he will never be able to fully reclaim his reputation — which would be a shame if, as he attests, he is truly innocent.