A Real Running Hero: The Flo Groberg Story

As a runner, it has been said that Flo Groberg “could suffer a little more than everyone else could” and was at his best when running a relay for his team. Two years ago today, he sacrificed his body for his team – the USA – in Afghanistan.

By Jonathan Gault. Initial interview conducted by Weldon Johnson.

August 8, 2014

Editor’s Update 10/14/15: It was announced today that Flo Groberg will receive the Medal of Honor – the nation’s highest military honor – from President Obama on November 12. We imagine many of the people reading this profile are people interested in learning more about Groberg and aren’t necessarily long distance runners. What you find below is a profile LetsRun.com did of Groberg, who ran collegiately at the University of Maryland, in August of 2014 when we turned over our entire front page to celebrate Groberg’s amazing story. LetsRun.com is a website dedicated to covering the sport of track and field with a focus on elite distance running and we honored Groberg as our runner of the month last year. For more on what LetsRun.com is, please go here. We consider our homepage to be the sport of running’s front page. We have a very popular messageboard where people posts about both running and non-running topics at www.LetsRun.com/forum/. If you have comments about Groberg, post them here: Wow: Flo Groberg – Our Runner of the Month Last August – To Receive Medal of Honor (Nation’s Highest Miliary Honor)

In some ways, Florent Groberg — known universally as Flo — was just like any other runner training for a race. In August 2012, as college runners across America prepared for another cross country season and the Summer Olympics took place in London, Groberg was preparing for a Labor Day 10k, one of the first steps toward his goal of competing in the US Army’s Best Ranger Competition in April.

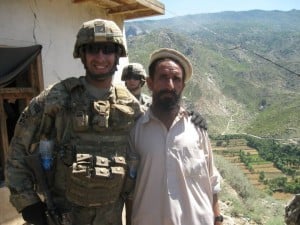

In other ways, Groberg was nothing like the runners logging miles across the roads and trails of America. Groberg, a captain, was stationed in eastern Afghanistan as part of the 4th Brigade Combat Team out of Fort Carson, Colo. Groberg had two options for runs: a 3.5-mile loop around the base (it was too dangerous to risk running anywhere else) or the treadmill, Groberg’s last resort when the cruel Afghan sun drove the temperature up to almost 120 degrees. And running was just a small part of Groberg’s training for the Best Ranger Competition, a grueling contest held annually in Fort Benning, Ga., that pits the best two-man teams of Airborne Ranger-qualified soldiers against each other. Distance running is part of it, but there’s also push ups, sit ups, marksmanship, obstacle courses and whatever else the organizers can think of to test the competitors over a 60-hour period with no breaks for sleep built in.

On August 5, Groberg ran 10:15 for two miles on the treadmill. This effort, like all of his runs, came after working a full day’s shift. He felt good about it and felt even better after he hit his maxes during a lifting session that night, benching 275 lbs., squatting 425 and deadlifting 450. Groberg was excited about how much better he could get during the five months before the Best Ranger tryouts in January.

Three days later, like many athletes, Groberg suffered a setback, one that clearly demarcated him from your average runner. It was the difference between the person who enjoys freedom at home and the one who goes overseas and lays his life on the line to protect that freedom. On that day, Groberg was tested, and he responded the only way he knew how — by putting himself in harm’s way to save lives and complete his mission.

There would be no Labor Day 10k. There would be no Best Ranger Competition. Two years later, Groberg still can’t even run.

***

“All it takes is one crazy to create havoc”

On August 8, 2012, Groberg was in charge of a team of six men whose job was to protect their Brigade Commander, Colonel James Mingus, who commanded the approximately 4,000 men deployed to Afghanistan from the 4th Infantry Division’s 4th Brigade. It wasn’t an easy job. Personal security requires constant focus. Everything that moves is a potential threat, especially “outside the wire” (off the base). But it was easy for Groberg to feel loyalty to Mingus. Like Groberg, Mingus was a runner — Mingus’s best event was the 800 — and to Groberg, protecting Mingus was more akin to protecting a father than a colonel.

That morning, Groberg and his men departed the town of Jalalabad in two UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters, arriving at Forward Operating Base Faiz in Asadabad. They were to escort Mingus, five other colonels and an Afghan general to a meeting with high-level Afghan officials where they would discuss security plans for the province. Before leaving, Groberg told his guys, like he always did, that anytime they left the wire, there was a chance they might not make it home.

“I call it playing Russian Roulette,” Groberg says. “You play with the odds. Every time you come home, you’re good, but every time you take off again, the odds are higher that you’re going to get attacked…All it takes is one crazy to create havoc.”

The walk to the Afghan compound where the meeting would take place was about a mile from the base. Groberg had done this patrol before; he was stationed in Kunar Province during his first deployment, from 2009-2010. Their route would take them down a curvy road before heading straight for about 600 meters, crossing a bridge and walking up a big set of stairs toward the compound. At first, everything was normal. Groberg and his team kept their heads on a swivel, checking cars on the route to confirm that they were empty and making frequent eye contact with each other.

Then, about 200 meters from the stairs, Groberg saw two men on motorcycles speed down the road and dump their bikes before sprinting toward the compound. Included in Groberg’s patrol were four Afghan National Army soldiers, and they quickly took off after the men. It was then that Groberg looked to his left and noticed a man in black clothing about 10 meters away following his patrol with an “evil” look in his eyes.

“What are you doing?” Groberg thought to himself. “Why are you so close and why are you here right now after those two motorcycles?”

The two made eye contact and the man made a hard 90-degree turn into the patrol, directly toward Col. Mingus.

Groberg shoved the man with his rifle and screamed at him. As he shoved, him, he felt a bulge under the Afghan’s shirt. “Oh shit,” he thought to himself.

“My heart kind of stopped,” Groberg says. “I wasn’t 100 percent sure exactly what it was but I knew he was bad.”

Groberg and his radio man, Sgt. Andrew Mahoney, didn’t hesitate. They knew they had only a second or two to get the man away from Col. Mingus, so they threw the man to the ground. He landed a meter away from Groberg and released his trigger, exploding his vest, which was rigged with explosives and ball bearings. The force of the blast launched Groberg 5-10 feet and knocked him out for about a minute.

When he came to, his fibula was sticking out of his leg and skin was melting off his foot. Chunks of flesh were missing from the left side of his leg. Groberg felt no pain, just an incredible numbness. The blast had kicked up a huge cloud of dust, making it difficult to see. Everything was moving in slow motion. Groberg was in shock.

Suddenly, the world whooshed back to full speed. Groberg thought the suicide bomber was the prelude to an ambush. He was still in the kill zone; he knew he had to get to safety ASAP. His rifle was nowhere to be found, so Groberg drew his pistol and began crawling away. Groberg’s platoon sergeant finally located him and tossed him into a ditch where the group’s medic, Spc. Daniel Balderrama, was waiting for him.

“You’ve got to save it, doc!,” Groberg yelled. “You’ve got to save my leg!”

In that moment, Groberg wasn’t thinking about saving the leg for running. It was difficult to think about anything at all outside of the profound thirst he felt and all of the blood he was losing. He just knew he wanted to keep his leg.

Even though the blast had blown out the PCL and MCL in Balderrama’s left knee and lodged shrapnel in his arm, Balderrama had a job to do. Blood was pouring out of Groberg’s left leg; torn flesh poked out of a hole in his pants. Chunks of the bomber’s bones were lodged in Groberg’s thigh. Balderrama applied pressure to Groberg’s groin, put on a tourniquet and wrapped the wound in a dressing.

Stabilized, Groberg needed to be taken away for emergency surgery. Two soldiers grabbed Groberg and began to carry him, but he stopped them.

“I’ve still got one good leg!” Groberg said. “Pick me up!”

And so they stood him upright and, with the support of his fellow soldiers, Groberg hobbled toward the truck that would drive him away.

As Groberg was heading toward the truck, he noticed several bodies on the ground. Unbeknownst to Groberg, while he was knocked out, a second suicide bomber had approached from the opposite direction. After the second bomber saw Groberg and Mahoney take down his comrade, he had detonated early but still managed to kill four people. All Groberg wanted to know was whether Mingus was alive.

He received the confirmation: Mingus was okay. Groberg and Mahoney had done their job.

Then Groberg noticed the bomber’s leg lying on the ground. Groberg wanted to kick it, but his injuries made that impossible. He saw the bodies of the four men who had lost their lives –– Command Sgt. Maj. Kevin Griffin, Maj. Thomas Kennedy, Air Force Maj. Walter Gray and Ragaei Abdelfattah, a volunteer with the U.S. Agency for International Development.

“Are they KIA?” Groberg asked.

“Yes, sir,” he was told.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, sir, I checked their pulses. They’re gone.”

Groberg’s attention was drawn to a sickening sight. An Afghan civilian was standing over the deceased, smiling broadly at the loss of life.

“It looked like he had the biggest Christmas gift ever,” Groberg says. “[He] looked like a five-year-old and you give him the train set he’s been dreaming of… and it was my friends on the ground.”

***

“I wanted to end him. I looked at him and thought, ‘This is everything that’s wrong with my enemy.’”

Groberg was never more at home than he was on the battlefield. To him, there was no greater thrill than facing enemy fire alongside his brothers. But this was much different. Seeing the men he was charged with protecting – his friends – lying dead on the ground, caused a wave of anger to wash over him.

In that moment, driven by rage and still clutching his pistol, Groberg wanted to kill the Afghan.

“I wanted to end him,” Groberg says. “I looked at him and thought, ‘This is everything that’s wrong with my enemy.’ I’ve never looked at an enemy that was dead and smiled. I’ll go out and fight the enemy but I’ll respect them as much as I can. But the fact that he could look at Gray, Kennedy, Griffin, Abdelfattah and be happy…”

His fellow soldiers noticed Groberg’s anger and began to calm him down. They told Groberg to let it go, that it wasn’t worth it. Two years later, Groberg is glad he didn’t shoot the man and knows that immediately after the bombing, he wasn’t himself. Shooting the Afghan out of anger would have been a mistake and Groberg is thankful to the men who convinced him of that in the moment.

Finally, he reached the truck that would take him away from the scene. It wasn’t designed for medical evacuations, so Groberg had to improvise, putting his leg in the left passenger seat, his back under the gunner’s hatch and his head in the right passenger seat. As the door closed and the truck drove away, Groberg was hit with dual realizations.

First was the pain, “like someone had a blowtorch and was burning my leg.” And then came the moment when Groberg realized that what had just unfolded wasn’t a scene from a movie or some training exercise – it was the real thing.

“No way,” Groberg thought. “That just happened.”

Groberg’s next few days were a whirlwind. After his initial surgery 10 minutes from Asadabad, he found himself back in Jalalabad. He doesn’t remember if he had surgery there — he’s had 33 on his leg since the injury, so they blend together — but was quickly transported to Bagram Airfield, the U.S.’s largest military base in Afghanistan, where he was given his Purple Heart. Or, as he likes to joke, the “Taliban Marksmanship Award.”

From there, Groberg flew to Germany for three days of surgeries. He was told before one of them that there was 75 percent chance that he would wake up with a leg amputated below the knee.

“I was so drugged up at that point, I didn’t care,” Groberg says.

When he awoke, his leg was still there.

Finally, he was transported to Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. The plan was for Groberg to be flown to a hospital in San Antonio, but one of his commanders knew Groberg was from Maryland and made sure that he would remain at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

“I told them, ‘Y’all can send me to San Antonio, but you’re going to have to deal with my mom,’” Groberg says. “You think the Taliban are bad, wait until she finds out her son’s been flown to Texas.”

***

“I was hooked on the sport”

The story of how Groberg ended up in that bed in Walter Reed is long and twisting. Florent Groberg, now 31, was born in Paris on May 8, 1983, with dual American and French citizenship, the son of Larry, originally from Indiana and Klara, who is French-Algerian. Larry Groberg was a businessman and his job took him around the world. The family lived in Paris until Flo was six, then moved to Spain and back to France. He didn’t speak English until he was 11 years old. In middle school, he moved to the Chicago area before the Grobergs settled in Potomac, Maryland, where Groberg attended Walter Johnson High School.

A soccer player, Groberg only took up running when his mom forced him to run track in 10th grade but his heart wasn’t in the sport. While running 400-meter repeats on the outdoor track, Groberg would run his first one and walk slowly back to the school for a drink of water. By the time he got back, he’d have missed several repeats — just as Groberg had planned.

“Part of [coaching] in high school is trying to figure what to press on a kid to [get them to] become a runner in their mind,” says Tom Martin, Groberg’s high school coach. “Flo was one of those kids I could tell had talent but [he] just wasn’t a hard worker.”

One day during Groberg’s sophomore year, he was at a developmental meet at Hagerstown Community College. Martin told Groberg that he wanted him to win his heat. Groberg thought that was crazy talk.

But Groberg did win, and in that moment, a runner was born.

“I was hooked on the sport,” Groberg says.

Groberg dedicated himself to the sport with the hope of running at a Division I school in college. He’d visit sites like Dyestat daily to keep tabs on his rivals in Maryland and around the country. He still had his fun — one day, Martin recalls, Groberg and some teammates had to be driven back to school in a police car after they decided to do their run on I-270 — but no one worked harder.

Groberg ran in the low 9:40s for 3200 and in the 4:26-4:27 range for 1600. But in was in the relays that Groberg did his damage. Groberg’s teams won county and regional championships in the 4×800 — something about running with teammates seemed to bring out the best in him. Groberg met his goal of running D-I, graduating from Walter Johnson in 2001 and enrolling at UNC-Wilmington. The students there partied too much for Groberg and he transferred to the University of Maryland after his fall semester.

“If I was to stay there, I probably wouldn’t have graduated,” Groberg says.

There was one small problem. When he got to Maryland, he didn’t have a spot on the track team. After arriving in January, it took three months for Groberg to make the team, eventually catching on just in time to run at the ACC championships that spring, where he got “demolished” in the 10k, running 33 minutes.

Embarrassed by his performance, Groberg vowed to get better and spent the summer in Boulder, Colo. The University of Colorado had won the NCAA cross country title the year before; Running With the Buffaloes had come out a few years earlier. For a running nut like Groberg, it was the place to be, even though he had to sweep streets in order to pay for his rent. He was inspired by guys like Ed and Jorge Torres, the latter of whom would win the individual title for Colorado at NCAAs that fall.

“You see these guys and you’re so in love with their success and the way they train,” Groberg said. “You just want to go out there and be better. That mindset allowed me to go through some of the tough times in the military. Running contributed to my success in life. It built me into the person I am today.”

Groberg inspired the same drive in his teammates that the Buffaloes had in him.

“Some people were leaders, some people were followers, and Flo was definitely a leader,” says Matt Sanders, who was Groberg’s teammate at Maryland and remains a close friend to this day. “He would work so hard on the track that people would see that guy and it would make other people better. You’d see how dead he was after practice and just know that that guy gave 100 percent. If you’re running and the guy next to you is about to throw up and you’re not breathing heavily, you know you’re not doing it right.”

Groberg always made sure to congratulate teammates after a PR and could always be heard roaring for them from the sidelines. One of his teammates, Pete Hess, said that having Groberg as a host during his official visit was one of the main reasons he chose to enroll at Maryland.

“You meet different people and get the feel of who’s just taking it as ‘I have to entertain this person for 48 hours’ and who genuinely cares about people and wants them to come there,” Hess says. “He was a fantastic leader and motivator. He’d message me before big high school races and really pump me up. In college, he was always supporting me and was genuinely happy for me.”

Though he was famous for his intensity on the track, Groberg still liked to joke around, engaging in a prank war with Hess and his roommates during Groberg’s senior year. One day, Groberg and his friends covered all of the doorknobs in Hess’s house with peanut butter, forcing Hess to enter through the window. Hess and his roommates responded by launching 400 eggs at Groberg’s house, causing Groberg’s very annoyed landlord to hose down the place at 2 a.m.

Groberg was versatile, running everything from the 800 to the 10k and earning personal bests of 3:53 in the 1500m and 8:24 in the 3k. But his best event was one that wasn’t run in individual races: the 1200m leg of the distance medley relay. It was fitting for a man whom his college coach, Michael Garrison, refers to as “the consummate teammate.”

“Looking back, when I see Flo, I think of Flo running with a baton,” says Garrison. “He was the guy you wanted to have on that relay, in your top five running cross. And if he didn’t make that five, he was going to work his tail off to make sure that you’d have to run fast to get that spot.”

Hess, too, says that the races he remembers most from Groberg were distance medley relays, where Groberg would run the leadoff leg.

“He’d hand off with the leaders even though there were guys in that race that definitely had more talent than him,” Hess said. “The 1200 is a hard 800 and you basically hold on for 400. That was perfect for Flo. He could suffer a little more than everyone else could.”

***

“I’m an American, my country was at war. I didn’t understand why other people had to go fight for me…..I was put on this earth to run track and shoot guns and defend people”

After graduating with a degree in psychology in 2006, Groberg took a job at iCore Networks, a voice over IP company in Washington. He was there for two years before he came to a realization. Groberg was making good money, but he hadn’t run a step since he graduated. His once-taut core had given way to a beer belly. He hated waking up on Sundays and knowing he had to work the next day. Worst of all, he felt that he wasn’t doing something worthwhile with his life. That was when he knew he had to join the military.

It was something Groberg had long thought about doing, dating back to 1996, when his uncle was killed by terrorists in Algeria. He had gone through Officer Candidate School while at Maryland and went through training to join the Marines. But to officially enroll in the Marines, Groberg would have to renounce his French citizenship and go through the training again. Groberg decided that the Marines wasn’t going to work out, but he began the process of renouncing his French citizenship with an eye on the army.

After almost two years, the French government allowed Groberg to renounce his citizenship and, in 2008, Groberg enrolled in the Army. It was an easy decision and his career change didn’t come as a surprise to his friends or coaches, who recognized his natural leadership abilities and love of the country in which he spent his adult life. His parents were very supportive of the decision.

“I’m an American, my country was at war,” Groberg says. “I didn’t understand why other people had to go fight for me. To me, that wasn’t fair. I was put on this earth to run track and shoot guns and defend people. It was a calling.”

Groberg started running again to prepare for boot camp and immediately won over his supervisors at basic training by running in the low 10:00s during a two-mile fitness test. Groberg went through a slew of training schools and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S Army. He finished up by earning his Ranger tab after graduating from Ranger School in Fort Benning and was assigned to the 4th Infantry Division in Fort Carson, Colo.

Shortly afterward, he was deployed to Afghanistan’s Kunar Province in 2009. It took some time for Groberg to figure things out over there. Groberg was supposed to go through a combat simulation in Louisiana prior to his deployment but was instead rushed over to Afghanistan. It was similar to a backup quarterback coming in off the bench at the start of his rookie season — Groberg had the tools to succeed, but no amount of preparation could simulate a true combat environment. His platoon sergeant, Korey Staley, told him to shut up, watch and learn the first week.

Groberg did, and grew into a leader. He was in charge of the heavy weapons platoon, responsible for 26 men and seven villages in the province. As he led his men on daily missions scouting enemy positions — resulting in the occasional firefight — the locals would call him Governor Groberg, because every decision for those seven villages ran through him. Groberg’s base was under mortar threat, so the only place he could run was on the treadmill. After each day’s patrol, he’d try to fit in a run around meals and Call of Duty sessions. Groberg would also make his men run on the treadmill as well. Midway through his deployment, the treadmill broke. Groberg is convinced it was an inside job.

After Groberg returned to Fort Carson in 2010, his men could have called him another name: Coach. Groberg, then serving as an executive officer, saw many soldiers who thought they were in shape, only to fail miserably when it came time to run the two-mile fitness test. He couldn’t believe how slow they were. So he printed off some high school girls’ two-mile results and showed them to his men.

Embarrassed to find out that they were running minutes slower than 15-year-old girls, his men were motivated to get better. Anyone who couldn’t break 15:00 in the two-mile had to come to remedial PE with Groberg. He told them that he could get them to drop two to three minutes off their times in 90 days. About 75 percent of the 25 or so men stuck it out and saw their times plummet.

“People look at you in the military, and if you can run fast, (they think) you must have done something right and you must be disciplined,” Groberg says. “Those are characteristic traits necessary for a good leader in their mind. That helped me a lot to advance a lot quicker than other people.”

While his fitness won over his superiors, Groberg believes it was the mental aspect of running that was most beneficial to him during his career.

“The reason I was successful in the military was because of running. Because of that mentality you get as a runner, that integrity you have to build within your own self, that discipline of waking up in the morning and doing those long runs over the summer when nobody’s watching to become better.”

For Groberg, that attitude led to advancement and eventually took him back to Afghanistan and that day in August 2012.

***

“Just because you were dealt a shitty hand doesn’t mean you need to quit”

Groberg’s physical recovery has taken longer than he’d like. He had to remain at Walter Reed for a three months after the attack and was visited by lots of friends and family — even President Obama.

Physically, Groberg is still suffering from the suicide bomb attack. A return to his beloved sport of running may never happen. He must wear a brace to walk and still deals with nerve pain. He can’t feel his left foot, and most of the left side of his calf is gone. He has good days and bad days with the pain and frequently takes Ambien because he struggles to sleep.

There are days when Groberg wishes that someone had made the decision to cut off his leg for him; that he had woken up from that surgery in Germany with the lower part of his leg amputated. After his injury, Groberg was inspired by Maj. Kent Solheim, who lost his right leg after being injured in Iraq in 2007 and continued to run triathlons, qualifying for the Paratriathlete World Championships. With an amputation, Groberg probably would have spent less time in the hospital – he has amputee friends who were running again six months after surgery.

But Groberg isn’t ready to give up on his leg yet. Right now, Groberg is retired from running. He hopes that can eventually improve enough to be able to go for a five-mile run, even if he has to limp a little or change his stride.

“I’m just praying one day the pain will subside,” Groberg says. “I’m pretty good with dealing with it and technology’s amazing now. I figure suck it up and maybe 10 years from now they might have some super-robotic leg that you see on TV. I, Robot, you know?”

Mentally, Groberg is stronger than ever. He still thinks about the attack, but he hasn’t suffered from PTSD or any of the mental trauma that could be expected of someone in his position. While Groberg is waiting to be officially discharged from Walter Reed (he continues to receive outpatient therapy and works out six times per week), he works in intelligence for the Department of Defense and is getting his master’s in management from Maryland. At first, he questioned why he survived his attack while others perished, but he’s moved past that. He lives his life for the four people who died that day and their families, doing his best to inspire others, especially those in Walter Reed who were wounded far more seriously than himself.

Mentally, Groberg is stronger than ever. He still thinks about the attack, but he hasn’t suffered from PTSD or any of the mental trauma that could be expected of someone in his position. While Groberg is waiting to be officially discharged from Walter Reed (he continues to receive outpatient therapy and works out six times per week), he works in intelligence for the Department of Defense and is getting his master’s in management from Maryland. At first, he questioned why he survived his attack while others perished, but he’s moved past that. He lives his life for the four people who died that day and their families, doing his best to inspire others, especially those in Walter Reed who were wounded far more seriously than himself.

“Just because you were dealt a shitty hand doesn’t mean you need to quit,” Groberg says. “Take whatever situation happened to you, turn it around and help others.”

Groberg has received plenty of accolades for his bravery during the attack: two bronze stars, an Army Achievement Medal, an Afghanistan Campaign Star. He’s been nominated for the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest award available to a U.S. Army soldier after the Medal of Honor.

“An award’s the last thing I really care about, but if it does happen, it gives me an opportunity to represent the families of the guys who were killed in my attack,” Groberg says.

Groberg doesn’t know what he’ll do once he’s discharged from Walter Reed, but he knows he still wants to motivate people to overcome adversity, just as he did at Maryland a decade ago.

“Some people would never be able to go back into normal life, but returning 100 percent to himself after what he’s been through, that’s amazing,” his college teammate, Sanders, says. “He’s the same person now as he was in college, personality-wise. His experiences define him but they haven’t changed him. A lot of guys have been through a lot less and it’s changed their lives. They’re emotional messes.”

Indeed, Groberg was a dedicated fan of running prior to his incident — he’d check four sites while overseas: Facebook, ESPN, CNN and LetsRun.com– and remains so today. During his first deployment, Groberg says that the running community helped him retain his humanity.

“You’d turn into this beast who’s a professional killing machine,” Groberg says. “When we come back [from missions], I have you guys, I have LetsRun. It grounds me and makes me feel like I’m back home.”

Groberg doesn’t have many regrets from his time in the military. He knows he made the right decision and wouldn’t hesitate to lay his life on the line again if he were physically capable of it. But he does have one regret, and unsurprisingly, it involves running.

“On August 7 (the day before the attack), I got up in the morning, I went to the bathroom and brushed my teeth and said, ‘You know what? I’m going to skip my run today,’” Groberg recalls. “That was one of my biggest regrets because that could have been my last run. It’s the one love you have and you pass on it and when it’s taken away from you, it makes you realize that you can’t take things for granted.”

***

Editor’s note: LetsRun.com first heard from Florent Groberg in the summer of 2012. We don’t have his original email, but he thanked us for putting on our self-proclaimed “world famous” prediction contests surrounding the Olympic Trials. He said they and LetsRun.com gave him a sense of normalcy in Afghanistan. The next email we received from him was on September 1st. Unbelievably, he was thanking us for our coverage of the Olympics. He wrote, “Guess what! I’m back in the States and I got to watch some of the Olympics after all on TV ahha. I got hit by suicide bombers on 8 August and they got me at Walter Reed because my left leg almost got completely blown off. But great job covering the Olympics and the rest of the season.”

We’ve always wanted to highlight a “Blue Collar Runner Of the Month” on LetsRun.com and felt someone in the military would be a great candidate. We’re proud to say Florent Groberg is the first Blue Collar Runner of the Month on LetsRun.com. From his 10:15 two miles on the treadmill in Afghanistan, to his 33 leg surgeries and still trying to run, to thanking us for our coverage of the sport of running, Flo is what the LRC community is all about. His service to country and self-sacrifice takes his accomplishments to a completely different level. We may not have another runner as worthy as being called “Blue Collar Runner of the Month,” but if you have a candidate email us.

***

Additional Editor’s note: We extend our condolences to the brave men who did not make it out of the attack alive: Sgt. Maj. Kevin J. Griffin, 45, Maj. Thomas E. Kennedy, 35, Air Force Maj. Walter D. Gray, 38, and Ragaei Abdelfattah. The Army Times has an article on the attack and Sgt. Andrew Mahoney earning a Silver Star (the nation’s third highest award for valor) for his bravery. The Colorado Springs Gazette had an article on Groberg last year.

10/14/2015 update: The Washington Post has an article on Groberg winning the medal of honor and Groberg says, “It was the worst day of my life because even though we defeated the enemy I lost four of my brothers. This medal is not about me, it’s about the four individuals that I lost. It’s about them, it’s about their families, it’s about true heroes that sacrificed everything for their country.”