Brutal: The Fan Experience at World Cross Country in Belgrade

By Tim O’Hearn

April 11, 2024

Commiserates have gathered once more. These weary travelers have met the Western City Gate. The route E-75 runs just beside this massive building, though, in a way, traffic flows through it. Between its legs, this keyhole of the Balkans. For pedestrians, vehicles, and other passersby, it has a halting effect. There is a toll to be paid. Demands, subliminal demands, are made of all those who witness brutalist architecture. The Western City Gate is an uncompromising columnal raw concrete framing of two towers of differing heights, bridged on the twenty-sixth floor with the slightest arch and featuring a circular capitulum. The taller tower is residential. The shorter tower contains office space which has been vacated. The circular capitulum used to contain a restaurant. Both sides of the office tower are enshrouded by full-length advertisements. It seems only logical that one features a cement truck. The circular restaurant was designed to rotate continuously but that machine has never run. Perched atop the bridge, though, is a digital clock, which keeps time just fine.

If the structure was larger, perhaps the bold gap between the towers would have taken the form of a question mark instead of an exclamation point. Therein lies the complication of this endeavor, or the curious natality of GPT-4 era content production. You see, in a dystopia, all buildings are brutalist. In a utopia, all buildings are blue-tinged glass or homages to the Hanging Gardens. In Belgrade, Serbia, it’s a funny thing that architecture so associated with socialist states of fifty years ago seems so prepared for what is yet to come.

Sometimes it really is best to consider a younger person’s perspective. A child does not ask why the Eye of London was erected, nor the Shard of that same city. When a brutalist building is presented, though, those slabs of vertical bedrock elicit fright. Light sobs of “Why?” Confusion pertaining to what appears to be an incomplete construction project. Stripped of artistic flair and familiar construction styles, westerners especially have little understanding of this artform. For the small-town millennial, the first exposure to brutalism may have been the distinct Forerunner buildings in the Halo universe. Or, the apocalyptic Battlefield 2142 which pedestals Belgrade as one of the last inhabitable cultural centers of Europe.

As tolls are paid, E-75 flows deeper into New Belgrade, a planned municipality where a grid cordons numbered superblocks. There are seventy-two in total. The blocks form a mosaic of grays, an immense stone quarry wherein some of the best examples of residential brutalism have been carved. Though development began in 1948, recently New Belgrade has become the central business district of the city proper. Previously, decades of nonmarket urban land use left Belgrade a disorganized, poorly zoned sprawl. The Danube River has been a mainstay, though, and it flows at a mellow diagonal from the northwest. One of its largest tributaries, the Sava River, is the boundary between New Belgrade on the left bank and Old Belgrade on the right. Historically, the marshes of New Belgrade were a no-man’s land that formed the buffer zone between the eastern and western Roman empires. Not having been besieged since 1999, the city is now wreathed by parks, with the main exhibit in New Belgrade being the Park of Friendship–Block 14.

Perhaps it’s by design that a building named a “city gate” overlooks the venue for an activity that is so often gate-kept. Cross country running is a peculiar sport. Yes, it involves running. And isn’t running universally understood? Try telling an immigration agent in Zurich or a sommelier in Venice that you’re going to Belgrade for a race. You’ll be met with an exasperated “… with the cars?” Maybe, if you then execute a running motion with sufficient elbow drive, you’ll receive an “… and you’re in it?”

What is World XC?

Cross country is an evolving discipline within a federation of like pursuits. It’s a footrace. There are some standard rules. Races take place on a natural surface that has been groomed but not infilled. The measured distance is in kilometers, certainly. Beyond that, what constitutes “true” cross country is up for debate. There is no other sport in which trueness and authenticity are so passionately debated. There is no other running discipline in which the finishing time, at least at the highest level, is almost totally irrelevant—

Oh, the course is pancake flat. The grass is too neatly trimmed. Now that new loop is too steep. Ah, that was a wet year, or was it a dry year? How many people ran the earlier races? Maybe add some obstacles. Nonono, don’t make it a Spartan Race. It’s hot and there’s no shade. Damn those kids from California who run Woodbridge instead of Van Cortlandt. Who measured this thing? Tangents. They changed the course again this year!—

Fans write off cross country times, at all levels of competition, with marked impunity. The definition of what it means to be a cross country runner competing in a true cross country race remains under lock and key. Cross country runners are all made out to be Prince Alexander Karadjordjevic: pretenders to the Serbian throne.

There is a certain draw to spectating a race on the roads or the oval. Whether it’s the Chicago Marathon or a high school dual meet on a behind-the-school track, those branches of the sport have some pull. Maybe not to TV audiences, but for those on the ground it’s alluring to follow the crowd and see what the excitement is about. Yet, erect stanchions on a muddy golf course on a windy day and it becomes a friends and family affair. Usually light on the friends, speaking from experience. When it comes to spectating cross country, there’s a question of: is this the right place? ShouldIevenbehere? Am I, you know, wanted? Are my services as a spectator of any value?

The paradox of the 2024 World Cross Country Championship in Belgrade is that I traveled to Serbia not knowing the answers to these questions.

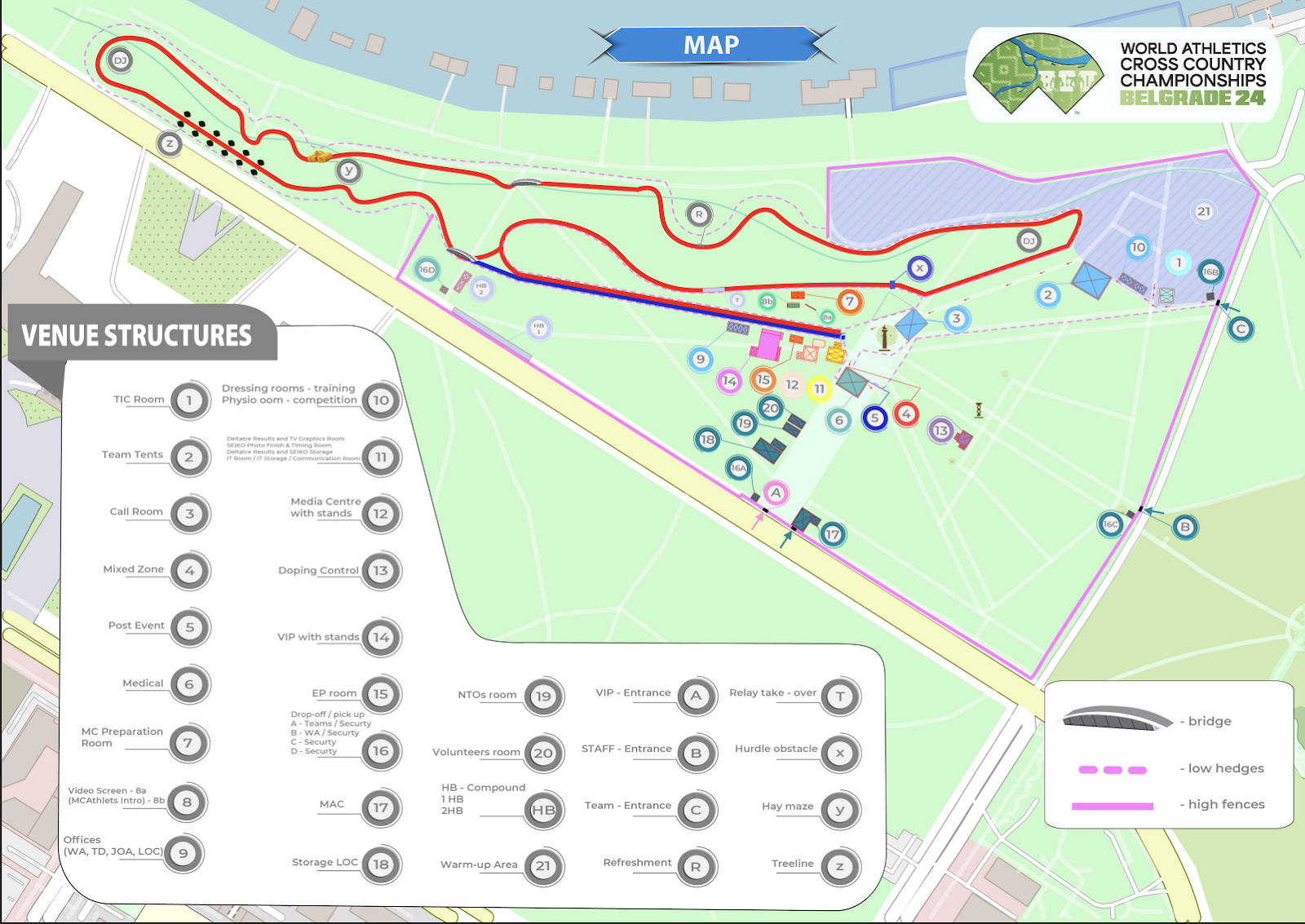

Spectatorship is an organic component of sport. At the higher tiers of competition, spectators readily pay prices and obtain tickets. They buy flights and book hotels on five days’ notice. Those people would be disappointed to learn that this year’s edition of World XC required a formal invitation. Media, support, athlete, or VIP credentials were required to access the fenced-in area within the Park of Friendship. Usually that’s beyond the purview of the spectator; it’s understood that certain areas should remain, ahem, blocked off. Unfortunately, this fenced area encloses roughly one third of the course’s main loop, as well as the starting and finishing segments. Though no viewing information was made public before the race, I did gather that the low-fenced outskirt of the course was free for spectators. Like the sadistic style of architecture, this artform has its share of detractors. It also has its share of interpreters.

I make my morning laps around the perimeter of the competition area. Searching for the most gullible security guards, searching for the most scalable fence, searching for the most panoptic view. The course loop is 1887 meters. Due to its slender profile, spectators and coaching staff will not be able to access the infield and mosey around. The whole settlement, including the fenced-in area, can’t be more than 2500m. That encloses a 270m starting straight and 320m finishing straight. The course is a badly misshapen paper clip from the era when paperclips had the requisite tensile strength and minds had the requisite imagination.

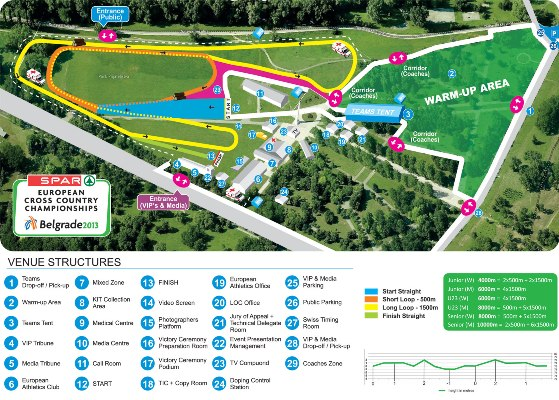

To give credit to the Serbian organizing committee, they offered to host this event just six months ago after World Athletics determined the committee from Croatia, the original host, hadn’t prepared sufficiently. While this course might have required some degree of imagination, it is an iteration of the two-loop course used on these same grounds for the European Cross Country Championship in 2013. The courses are similar in that:

- An organizing committee with a very limited amount of space to work with made it work. Though it’s like a motorcycle driver’s ed course being coned up in a strip mall parking lot.

- The course is pancake flat, so the times won’t be considered “true” cross country.

- It’s probably not even worth driving across town to be a general admission spectator.

The 2013 course, which induced vertigo as I watched some race footage, featured a short loop of 500m and a long loop measuring 1500m. Different combinations of the loops were created for the different races. In 2024, the main loop is the same for everyone, but, presumably, the now-parallel starting and finishing straights are adjusted in length to accommodate the leftover meters once 1887-times-whatever is calculated. Those events are:

- Women U20 – 6 km

- Men U20 – 8 km

- Mixed Relay – 4 x 2 km

- Women Senior – 10 km

- Men Senior – 10 km

The awkward, claustrophobic course design will make for an interesting race. A tight loop means more laps and more chances for stationary viewers to catch their favorite runners. Runners have more chances to catch each other with well-placed elbows or heel strikes. Whereas the 2013 Euro XC course contained tricky turns and small barriers (which did induce falls!), Hydraulic Pressed Paperclip has two tight 180-degree turns and an extra one on the first lap. Don’t dare call them hairpin turns. In addition, the course features a low hurdle obstacle, hay bales, newly-planted trees, more-mature trees with pads tied to them, freshly-watered mud, and two scaffolded steep hills (figuratively: bridges over the Sava River) that look like they belong at a skatepark. All of this together supposedly resembles the cross country of our forefathers–full of rhythm breaks (to say nothing of the two “DJ” areas placed at opposite ends of the course). Overall, the evolving hazards in cross country running are meant to bolster the mysticism of the “cross country specialist,” the runner who is born to run. The runner who might get trounced on the roads but comes alive on the dirt, even if that means coming alive on a course drawn by a U6 using a permanent marker.

Who is running the race? That’s complicated, too.

The easy part: every country on the planet with a federation in good standing with World Athletics can send a full team for each event. That’s six athletes per race and four in the mixed relay. There are no time standards. There’s no points system or ranking system. Each team is assembled at the discretion of each country’s federation. Some countries host national qualifying races, some use world rank, some genuinely seem to solicit volunteers. The message is that there’s enough room for everybody out there (even when there’s, clearly, not), so let’s spike up and see what happens.

The complicated part: World Cross Country carries less prestige than other championship events. This year, it’s wedged between the World Indoor Championship in March and the Olympics in early August, not to mention a packed calendar of lucrative road races and national qualifying meets. Of course athletes are assessing the prize money. They’re also weighing the tradeoffs of reduced recovery or blown periodization to run a grueling off-event. For collegiate athletes in the United States, for many of whom qualifying for World Indoor would have been a crowning achievement, sacrificing late winter base training (and spring break) to go to Belgrade and have Joshua Cheptegei’s spikes flick mud into their faces for at most two laps is not an appealing prospect. It’s even less thrilling to run on dirt when you log most of your mileage on manufactured surfaces. With this in mind, national federations are resigned to the fact that their best marathoners, road racers, and track studs will not indicate particularly strong interest in running the race. Some federations don’t send teams at all. Other countries, often those that spend more time training in “true” cross country conditions, relish in the toughness of the course. Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda will send strong teams.

To summarize, there’s a major cross country race in Serbia because Croatia hot-potatoed it. World record holders, gold medalists, and national heroes will be lining up against unproven talents, workout fodder, and ragtag groups. The course is designed to force contact and extract a physical toll; the race is held on a day on which it is 80 degrees Fahrenheit by late morning. Fans are left to concoct justifications pertaining to the non-appearances of their favorite athletes. They’re also left to concoct justifications for actually attending the race. There’s no view of the start or finish, no concessions, very little shade, and no public facilities of any kind. The whole thing is rather…

The First Race is Off

At 11:00 a.m., the U20 women are off. Figuring it would be sacrilegious to not catch the first navigation of the hay maze, that’s where I begin. From a distance, I can see a Japanese runner leading the race. I’m not sure if she ever makes it out of the maze. Disappointingly few athletes hurdle the stacked hay. Zariel Macchia of the United States is positioned well, in about 18th, with compatriot Ellie Shea just behind her. A few stragglers are already 30 seconds back. Maybe they had to sleep on a bare concrete floor last night. Watching the field crest the fake hill is not exciting at all. I shuffle toward the water station where there is a better view of the south segment of the loop. As runners approach the split mats at the end of the first lap, there’s a front pack of 15 with some viable chasers.

During my earlier surveying of the course, I noticed a few things. First was that there were probably 250 or fewer fans lining the course. Including athlete support staff who had exited the cloister and Serbs out for their morning walks along the Danube momentarily peeking at the action, maybe 300. There were confused families who had traveled great distances to see their sons and daughters compete just to realize at the gate that none of the entrances would be welcoming them in to cheer or to, you know, use the bathroom. Tense hands grasped temporary fences as moms and dads yelled into the warmup area.

The second thing was that the course map I had internalized wasn’t accurate. The northern segment of the course, which is where spectators end up crowding, has had a bit of rearrangement. The hay maze appeared much earlier, maybe 60m before the first bridge. The refreshment stand (for athletes, that is) is located shortly after the bridge, rather than on the bulge before the bridge. Finally, where I expected to find the hay maze, I found the mud pit. The mud pit wasn’t included in the published course map, but there it was, with a dedicated staff of two Serbs who turned out to be lively companions. Also, the concept of “low hedges” lining the course proved to be aspirational, as the boundary all the way around was a low fence.

I move to the mud pit for lap two. It has dried a bit in the sun, or so I’m told by Luka and Nikola, its maintainers. The women approach. The front pack has roughly 13. Kenya’s entire team, Ethiopia’s entire team, and Uganda’s top three. A Ugandan trails by two seconds. The fifth Ugandan is five seconds behind her with the Brit FitzGerald stuck to her. FitzGerald is breathing like she’s the first person to be chased after in a horror film. The mud has been baking and it doesn’t impede the leaders at all.

The First Fall

A minute later, there’s slipping and sliding. A runner from Australia goes down. The first fall! “The pit is working as intended.” The viewing angle from the mud pit turns out to be a good one, as there’s a line of sight to the leaders as they exit the newly-planted treeline on the south portion of the course. The narrowest parts of the infield are barely the width of the cement truck displayed on the side of the Western Gate. The bell signaling the final lap is soon heard in the distance.

Back for a final lap. Ethiopia 1-2 tailed by Kenya. The mud is deeper now and stabilizing lurches become more pronounced. The field is broken up and Uganda is perceivably a distant third in the team standings. Ellie Shea of the United States is chasing them. FitzGerald of Great Britain is chasing her and her breathing is no more labored this time around. As fast women are still coming through, the two Ethiopians are rounding the bulge on the other side of the course, having dropped the Kenyan. Anyone peering to the left before skipping across the mud would surely be demoralized at this sight–it’s information, just not particularly useful information since those runners are too far ahead and won’t be caught. An Australian, perhaps one thinking about her earlier fall, chooses to walk over the mud. As I’m explaining the nuances of cross country to my two Serbian friends, a spectator on the other side of the course begins squawking like a bird. “Is that a bird?” I’m asked, as if my knowledge of cross country translates to ornithology. We listen to another stanza of the birdsong before I declare: no, that’s a woman, yelling something that is definitely not “move!”

I sneak a glance to my left. Inside the private fenced area is the Eternal Flame monument. It’s the overseer of this park of friendship. A lighthouse to navigators of the rivers. It is dedicated to the casualties of the 1999 NATO bombing and to the Serbian spirit of resistance.

The Serbian crowd, gathering that it’s the final lap, grows excited. There must be a Serb coming. There is–it’s Jana Rajic. Seeing the mud pit, though, Rajic decides she has had enough. She avoids the pit by lying down just short of it. We begin hollering wildly, attempting to inform the entente of medical staff, postured around their Land Rover like they’re on a safari in the infield. They’re just yards away, but they can’t see Rajic behind the short canvas fencing. A member of the technical staff runs onto the course and tends to his compatriot, rolling her onto her side and checking her pulse. Finally, the medics notice and saunter over. Rajic won’t be finishing the race. She’s carried away by her limbs and placed next to a bush for further processing. The twenty of us lining the course who saw her race end this way admire her bravery.

We’re then ushered away, not for an ambulance but for a water truck. It’s revealed that over 5000 liters of water will be hosed onto the mud pit today. That estimate doesn’t account for the remnants of fans’ water bottles that they have started pouring into it as a gag. Drops in the ocean, ha-ha-ha. I laugh every time I see this dad joke of physical comedy reenacted.

An unbelievable amount of water is sprayed onto the dirt. In the foreground, the spouting water, in the infield, a parched Jana in the meager shade offered by bushes and being tended to–barely. In the background is the Palace of Serbia, the largest building in the country by area. It looms over the course as a compromise between brutalism and modernism. How it came to this is, of course, complicated.

I’m still at the mud pit as the U20 men fly by for the first time. Too many to count. What’s impressive is that three Japanese runners have embedded in the lead group with the next three fairly close behind. On the southern segment, it’s the same story. A man and his son, who is riding a bike with training wheels, begin plowing through the spectators’ corridor, ringing their handlebar-mounted bells and expecting us to move. Most of the northern segment of the course abuts a bike path. Spectators are standing on the path in the places where it’s hugging the course fence. There has been no signage posted and there is no detour, so a steady stream of recreators are committed to using the path as they would on any eighty-degree Saturday morning. They–correctly–glean that the running fans don’t have the resources, strength, or willpower to mount any resistance.

The second lap seems even faster. One Japanese runner is still up there. It is revealed that the Japanese team arrived a week prior to the race and have spent every day since measuring, analyzing, and running on the course. My friends at the mud pit find this level of commitment ridiculous, especially since there were last-minute changes made to the course. Okay, so I’m not crazy. A thought crosses my mind–maybe the course was changed because the perfectionist Japanese team determined that it had been mismeasured. Other passersby: the United States junior team actually looks good. Suddenly, a young-looking Serb is receiving immense support from an expanding crowd. Wow, this kid looks like he is fifteen! (He turns out to be fifteen.) The technical staff is being fed lap splits and finishing times for the leaders. Luka states: “I don’t think there is a world record for this.” He’s starting to put it all together.

On the next lap, it’s just Kenya, Ethiopia, and Uganda. Witnessing the stride length and form power over the mud pit is worth getting splashed a little. On the final lap, the lead group is five men. Three minutes later, an American is at his limit. Berkley Nance approaches the mud pit and falls. His teammate Birhanu Harriman sees this and almost–almost–stops to help. Though Nance makes it out of the pit on sheer willpower, he won’t be able to run the final kilometer to the finish line. We alert the medics, successfully this time, and they chase down Nance, beckoning him to halt. He halts.

I glance over at the Eternal Flame again. As far as I can tell, it’s not burning.

Mixed Relay

The mixed relay, which is ordered male-female-male-female, is off next. For this race, consensus seems to be that the hay maze will be most intriguing, especially on the first leg. There’s a variety of running styles seen here with surprising separation by the time the athletes come into view. And, perhaps most surprising of all, a Serb who is at least 6’5” is in fifth place going into the maze. I recognize his bib name–Bibić. I then remember that each runner only runs 2 km, meaning that this is a mid-distance race on grass. Bibić is impressive over the two bales he hurdles, leaping so far as to almost collide with the runner in front of him.

The south portion of the course is semi-obstructed by the fence, but I can still see that it’s a Kenyan in first with a Kenyan in the VIP zone running alongside his man. He’s flying a Kenyan flag. Ethiopia is right behind. There is also an Ethiopian in the VIP zone with an Ethiopian flag. Other than those two, the entire segment of the course seems devoid of human eyes. Bibić hands off the… baton bracelet… in third place!

Kenya and Ethiopia establish that it’s going to be a two-team race, a theme that is getting repetitive. Serbia gets caught. Ella Donaghu runs a monster lap to bring the United States into a distant third at the end of the second leg. The race is intriguing once again. Johnathan Reniewicki keeps the red, white, and blue in third. Great Britain’s Adam Fogg–street name FOGDOG–maneuvers his own red, white, and blue into fourth place.

On the final leg, the Ethiopian team has lost an inconceivable amount of ground before the hay maze. I will learn much later that Birri Abera’s left heel was stepped on in the exchange zone. She lost her shoe, ten seconds, and any chance at the gold medal. Kenya will win, Ethiopia has second. The US has crashed and it looks like Great Britain has taken third. We can’t tell. We can’t see the finish line.

The Women’s Race

Where were you when you found out Sifan Hassan wouldn’t be running the women’s race? This author was eating at a restaurant named Birdsong in San Francisco and had just passed his friends his phone to introduce them to LetsRun.com. The question “Who’s Sifan Hassan?” was posed immediately. Give me that phone back! Though relieved to see she hadn’t died tragically, I lost my appetite upon seeing the front-page story of her withdrawal from the senior women’s race. Without the unicorn Sifan Hassan, focus shifts. Kenya’s team can place five runners in the top ten. America’s Weini Kelati and Norway’s Karoline Grøvdal both have decent chances of finishing in the top ten, amazing achievements for non-cross-country countries.

But, chiefly, Kenya is poised to turn in one of the greatest team performances of all time.

Kenya’s top five fight for every inch – TIM O’HEARN

They do, and in short order. It’s Kenya 1-2-3-4-5. They run through the mud pit as if it’s freshly poured concrete and they want to leave shoeprints. They move as a unit. The only aspect not synchronized is the runners’ arm carriage. It doesn’t matter. The rest of the field is running like they’re carrying bags of coarse sand. The Kenyans are overclad with the particulate of cross country success.

By the fourth lap, the crowd’s interest is waning. It’s terribly hot in the sun, and the bike path is active as ever. There is a constant stream of angry cyclists and angrier rollerbladers. The Serbs who do stop to watch are bemused, if just for a few minutes at a time. When Chebet, Rengeruk, Kipkemboi, Achol, and Ngetich pass by, folks step back, halt, cautious of the splashes of mud, frightened by this ferocious sojourn.

The top four runners are scored in World Cross Country. Kenya scored ten points and would have nabbed fifteen if their fifth runner had counted. Using the published lap splits as a proxy for a 10-km-to-8-km conversion, Kenya’s top five would have run somewhere between 24:23 and 25:20 for 8 km. Just taking the average finishing time and calculating the average per-kilometer pace, it’s around 24:56. If this female team was unleashed against the men’s U20 field, they likely would have edged out the United States men for 7th place in the team standings.

“If Cheptegei does not win, he is done.”

I ask the Ugandan student studying in Belgrade to repeat himself. He does. I then ask if Cheptegei is seen as a national hero. He says that he is. With a few stipulations. I listen intently but don’t understand any of the stipulations. At no point does he mention real cross country. When I ask the student whether he himself ever ran, he begins by saying yes and goes on to mention that he injured himself dancing and now no longer dances or runs. Funny, I tell him, because I’ve never met a runner who dances without looking like he’s injured. He then mentions the unattainability of the maximum allowable racing weight for someone of his stature. With a rough conversion from kilometers, I recognize this as my weight around the time that I was playing Battlefield 2142.

It’s a good day to be a Ugandan. Though the country is a bridesmaid on the world stage, there is a venerable level of success in what is seen as an upstart distance running country. Kenya and Ethiopia have richer histories, better funding, better infrastructure, and better coaching. It’s a really good day to be a Ugandan if your name is Joshua Cheptegei or Jacob Kiplimo, because everyone, including those lining up next to them, expects them to win, place, show, or go home devastated.

At the hay maze, an Indian named Hemraj Gurjar leads the field by over 100 meters. “Alright!” Fans don’t track him with their camera phones. They keep them pointed at the pack that is approaching. There’s nothing of note here, it being lap one, but the student next to me is shouting “CHEPTEGEI–CHEPTEGEI–CHEPTEGEI!”

Gurjar has emptied the tank on lap one and doesn’t manage to hold his lead into the second lap. The Ethiopian Chimdessa Debele has 20 meters on the field now and he’s taken more seriously as the Ethiopians are known to sacrifice runners for the betterment of their team. There’s no development in the pack. On the south bridge, Debele is caught.

At the mud pit, there’s a single Kenyan breakaway, perhaps their own sacrificial lamb, their own bridge builder risking his life to construct a monument. He’s followed by a tight pack of Kenyans, Ethiopians, and Ugandans. The runners circulate the course. To this sunburned fan base, and even to the VIPs in the air-conditioned tent, these men are everything. Viewed from the windows atop the Western City Gate, they are flies splattered on the windshield of Southeastern Europe.

It’s the last lap now. Kiplimo buzzes past. Aregawi. Too fast for me to read the bib. Cheptegei. Masai. Too fast for me to read the bib. Kenya will win the team title. Kiplimo will win the race. I hold my breath. On the south branch of the course, Kiplimo has separated further. A Kenyan and an Ethiopian chase. Two Kenyans. Cheptegei. The best Cheptegei can do is fourth, and that would take a lot. He hangs on for sixth.

The race is still taking place for most of the field; a different Ugandan hooligan is running along the bike path chanting “Uganda!” It’s pronounced with the D sounding more like a T, and articulated that way, it’s commanding. He’s stopped several times by groups of Serbs who seem to want pictures. They are searching for proof that this all really happened.

Now, of course, there are many ways to write off this race, or these races, as not having been real. But, this time, I saw it all with my own eyes. The men’s race was real enough so as to pencil in the zenith of Cheptegei’s career. He’s not “done,” but this was an unsatisfactory mark in his quest back to the pinnacle. In every era, societies must answer the question: who among them is considered “great”? Here in Belgrade, the first step to greatness is simply lining up and running the race. The next step has been taken by another Ugandan. Jacob Kiplimo has defeated everyone else who showed up. The epitaph on his grave may one day read: here lies the natural born runner.

The Aftermath

I shake hands with my two Serbian friends as I depart the Park of Friendship and begin a journey over the bridge to Old Belgrade. Within two hours, I reach Novo Groblje. Belgrade’s New Cemetery is one of the most notable in Europe. The sculptures are exquisite, the history is unbelievable, and the degree of self-expression found in many of the memorials makes you forget where you are. Many of the graves feature circular monochromatic pictures of who is buried beneath.

Runners debate: is it appropriate to run in cemeteries? I’ve taken that further and asked if it’s appropriate to run shirtless, run fast, or run at night in places of eternal rest. Is it appropriate to drink from the water spigots if you get thirsty? Years ago I published an article dedicated to the topic of running in graveyards.

Novo Groblje makes me feel pretty ridiculous for writing that article. Not only will I not run or take my shirt off here, I tread lightly. Some vaults have collapsed, or have been looted by graverobbers, and I fear tripping as I step over them in the narrow alleyways of the eternal rest. There is an ever-present feeling that misbehavior could be met by a fissure opening up in the Earth and dropping me straight into hell.

The graves provide views into passions, likes, and likenesses. It’s a museum of Serbian life and Serbian struggle. Serbian status and Serbian strife. Affiliations. Those remembered for having won battles. Those remembered for having lost them. Fallen angels and weeping wives. A soaring eagle and a statue of a man wearing boxing gloves.

I arrive at Giovanni Bertotto’s grave.

Bertotto, a famous sculptor, speaks of man’s triumph over stone. The splitting of granite. The dominance over the natural world in reinforced concrete and modern construction methods. Some of those buildings hang over the cemetery now and bow their heads to manipulators of solid mass. I think about the runners today. The falls, the faints, the cracks, the fragmentation, the leaps, the chops. Those images could all be memorialized in a place like this, if only we still had sculptors like Bertotto. If only we still had space in the cemetery. Somebody ran their last, best race today, but it’s the Serbs who seem most prepared to die.

Further back, the plots are smaller and less grandiose. The sun is setting on the crooked teeth of Novo Groblje. Some graves are so close together that they are colliding. Tectonic plates wherein their occupants are actually kicking and “rolling over” in the afterlife. Uneven stone crypts. Headstones toppled over. Soil freshly tilled. Fresh flowers stacked neatly.

I’m approaching a life-sized statue in a stance that is familiar to me. There’s a bit of elbow drive, maybe a bit of a back kick. Could it be? From behind, it appears to be the facsimile of a runner. I hustle over. I’m disappointed to see any grave, really, but I’m more disappointed to see this one because it ends up being a statue of a man playing football. His right foot is positioned to balance the soccer ball. Much later, thanks to my Macedonian friend’s knowledge of Cyrillic, I’m surprised to learn that this man was never a professional footballer. Then I learn the probable reason that his headstone is entombed by plexiglass.

I backpedal to New Belgrade as night falls. There is almost no trace of the cross country meet now. I don’t blame people for not logging any extra mileage on the sidewalks here but they happen to be just to my liking. Pedestrian paths are straight, well-maintained, and are usually at least a quarter-mile long. These conditions are dictated by the surrounding buildings. This just isn’t one of those European neighborhoods with that romantic, bohemian appeal.

Yet, there’s no danger. I no longer feel the presence of the cemetery dwellers. I cross E-75 past the Western City Gate and I’m jogging southwest. The first sight is the 35-acre Block 65, built on the grounds of an old airport which was destroyed by the Germans in 1944. This new development broke ground in 2005. It’s called Airport City. Entering Block 64, there’s a gate to IMT, an industrial agricultural machinery manufacturer that sponsors a top-tier Serbian football club. There’s a human guard there now and on Google Street View there are four veritable junkyard dogs. Okay, it’s a bit ominous.

I enter Block 63 but the view is obstructed by trees and more recent constructions. I trace my hand along a building as I pass. The surface chafes the delicate flesh of this keyboard warrior, offering the passerby a fingernail file should he dare to press a bit harder. Crossing a dead-end street and walking through a surface lot, I shift my eyes skyward.

Blocks 61, 62, 63, and part of 64 are a Mecca of brutalist urban planning. Together, they form the Bežanijski Blokovi (Bežanija Blocks, named after an 18th century settlement), a neighborhood of 40,000 residents. A maze of prefabricated concrete and two-room flats. The achievement of unskilled labor and centralized power. The Serbian resistance. Here, I’m a humble observer. Once again not sure if I’m invited, once again paying some toll. I keep checking over my shoulder for the chase pack. There’s greenspace, more than anyone expects, and some of it is lush. That just means unmaintained, I think. Luka and Nikola don’t live here, they are not custodians of this course. They live in Old Belgrade.

Within Block 62, I find a simple swing set surrounded by tall grass. It has a thick chain and a seat suspended over a laceration of dirt. I finally sit down.

Some time later, I’ve taken a left turn and I’m walking toward the left bank of the Sava, along Block 61. Slender men are standing in a circle smoking cigarettes. Muscular men are gathered around a basalt-colored clown car doing nothing at all. I want to ask them, what is brutalist architecture? A parking garage with slits of glass. The underside of a highway overpass with a few boreholes. Functional ruins. Anything that doesn’t take well to paint or shingles. Prefabricated superstructures in state-sponsored opposition to folly and wastefulness.

“It is brutalism–very ugly.”

Scholars have called New Belgrade “an ugly field of housing blocks.” Concrete in so many of its forms so forcefully meets greenspace. And somehow others see no beauty in the workmanship of these monuments and their grounds. Only ugliness. Sharp turns, undulations, manufactured hills, some gaps and scrambles await the thrill-seeker. Yet, we’re talking about grass and dirt. For how many times today a spectator looked around and pondered “what have I gotten myself into?,” it feels as if Block 61 has been sitting and waiting for fifty years to incite the same line of questioning. It is an aesthetic that so neatly aligns with this sport. Struggle begetting struggle. Strength winning strength. The World Cross Country Championships might as well have been contested on the grassy patches in the shadow of these grotesque apartment blocks.

The After Party

Another left onto Ulica Jurija Gagarina (Yuri Gagarin Street) and I’m headed toward the bridge to Old Belgrade. The remaining distance is long and I consider rerouting to the hotel. At the exact moment that I congratulate myself on not getting into any trouble, I manifest a wild dog. I outsmart the dog. It seems more lost than vicious. Close to the bridges, close to the hotel, there’s a soundtrack. Loud music. It’s being played outdoors and this amplification is not a car’s audio system. Can I crash a Serbian wedding?

The bass line is familiar to me. I cross the street, unable to determine what type of structure I’m approaching, unable to determine if I’m about to be arrested or, worse, chased by a dog. I begin walking down a path next to a parking lot. The music is coming from a place not too far away now. As I continue walking, through the fence I see some vehicles. I see buses and they have the World Athletics branding. This is some type of party for World Cross. Only, I don’t have real credentials to begin with, and I dropped what I did have off at the hotel. This is not a temporary fence and it’s not one I’ll be hopping. I reach the end of the path, take a tight turn, and find myself at a jumpable barrier at the guard’s station. I straighten my posture and drive my elbows back as I approach. I can’t run past this guy. I don’t know if I can clear the parking gate. I pull up the Photoshop document on my phone. It says Tim O’Hearn Journalist. One gatekeeper waves this one in. It’s an exclusive event venue that looks so new that I’d believe it was completed just in time to host this party. It’s packed with athletes, coaches, media, staff, VIPs, and at least one man who is none of the above. But for an hour, he felt like he belonged.

—

Tim O’Hearn is a software engineer who lives in the West Village. He runs with Central Park Track Club.

Strava | LinkedIn | Email

Other articles by Tim: Places of Work – Millrose Games 2024