Guest Column: How Bravey Could Have Been Braver

Guest Column by Kate Raphael, @KateRaphael, kateraphael.org

February 9, 2021

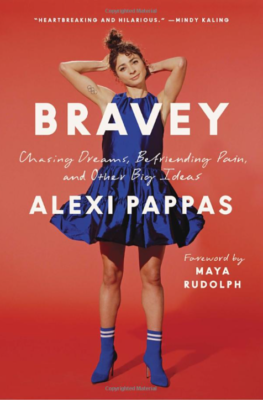

Alexi Pappas, Olympic runner and indie filmmaker, is now a published author, having just released her memoir Bravey: Chasing Dreams, Befriending Pain, and other Big Ideas. The title of her book comes from a short poem she wrote: “run like a bravey, sleep like a baby, dream like a crazy, replace cant with maybe through sunny & shady.” It blew up on the internet, and “Bravey” stuck as a moniker for her fans, mainly young women runners. Pappas tweeted her Bravey poem days after I walked on to my college cross country team after a summer of nursing a bone injury, and I resonated with the power of betting on yourself, through “sunny,” but especially through “shady.”

I’ve long followed Pappas’s athletic and creative pursuits, and she’s gained my tremendous respect; as a competitive runner and writer myself, I opened her new book eagerly. Bravey is a delightful read, jam-packed with lessons learned and the advice Pappas carries forward from her experiences. She tells her story charmingly, candidly, openly, talking about the hard-to-talk-about things.

Her message of “puberty power” is critical and timely for girls who are about the ride the wave of physical and emotional changes and her story of allowing her body to develop naturally is a positive counternarrative to the unsustainable pattern of girls and their coaches fighting nature’s course in an attempt to maintain the shape of their prepubescent bodies. Pappas deftly navigates the challenges of outgrowing coaches, teams, towns, and relationships, acknowledging how they have all made her the person she is, writing: “For every fun moment of victory in this book, there are uncomfortable and humiliating moments, too. I am the sum of all of them…This book is about making a life, not just living a life. We will grow up together here.” She expresses gratitude for the mentorship she has received from so many people, women and men, peers and coaches, and writes as a mentor to future generations of athletes, imagining her readers as younger versions of herself. Pappas is vulnerable about her struggle with depression and how it offered her an unexpected connection to her mother; she is open about her initial denial that she needed professional help, and she writes with self-assurance about the strength of finally asking for it, putting in the energy to heal her mind, just as she would devote energy to healing her muscles and bones.

Purchase Bravey here.

Purchase Bravey here.

And while all of this is important, I was left troubled by some of the language present throughout the memoir and the effect this language could have on young women athletes, a significant proportion of her readership. Pappas gets it right so much of the time, so when she gets it wrong, it eats at me.

Much of the book focuses on her mother’s struggle with serious mental illness and eventual death by suicide. Pappas recognizes correctly that her mother was suffering from a disease, that her many doctors and medical institutions failed her, that her death was preventable, and above all, not her mother’s fault. And yet, I was disheartened by Pappas’s repeated use of the phrase “kill herself” rather than “die by suicide.” Pappas does important work to undo the stigma attached to mental illness, but she isn’t able to depart from this language that places blame on her mother.

I don’t pretend to know how Alexi Pappas has worked through and healed from her mother’s death. I don’t pretend to know what sort of emotions are still wrapped up in processing this tragedy, whether or not there is resentment and hurt that still remains. Whatever Pappas is feeling is okay, but she made a choice to use the words “kill herself,” and that choice carries weight. That phrase shifts agency and blame onto the person who died by suicide, further entrenching the stigma wrapped up in mental illness. Just as we would not attribute personal agency to someone’s death if they lost a battle to physical illness or because their doctors didn’t provide them the care that could save their life, we should not place this agency on those suffering from mental illness.

I also found myself frustrated by the way Pappas talks about women’s bodies. In her chapter “The Rules,” Pappas discusses her understanding of what she coins the “Dorm Room Rule,” where she felt obligated to have sex with men in college once she had crossed the threshold into their dorm rooms. Pappas explains how her thinking evolved from believing she owed boys sex to embodying her identity as a sexual actor with her own desires, yet she still reinforces false, damaging ideas about virginity. Pappas says, “with virginity, it is taken instantly.” Despite having a complex, nuanced understanding of her own mind and body and the ways she has changed and grown into herself, she won’t put down the archaic idea that we are “losing something” when we have penetrative sex for the first time, and that our identities fundamentally change in that moment. The idea of virginity is a patriarchal, heteronormative concept that diminishes our agency and attaches guilt and shame to a narrow definition of sex. Pappas takes pride in her body and what it can do, and in other moments of the book she is decidedly sex-positive, but it was difficult for me to move past this limited understanding of sex as transactional.

Pappas is imprecise when talking about women’s bodies in other moments, sometimes using the wrong word to name body parts. Her mother died when she was 5, so the first grown women she remembers seeing naked were her friends’ moms. She describes watching them change in locker rooms and says: “This is how I was introduced to the adult vagina. I remember all the mom-vaginas I ever saw because it felt like seeing a sea otter in the San Francisco Bay: not impossible but definitely not an everyday occurrence. It was thrilling to catch a glimpse of what I might expect from my own body one day.” Once again, Pappas is so close to sending the right message, recounting grown women who were not ashamed of their naked bodies and who imparted knowledge onto Pappas about how she would physically develop in the future. But Pappas uses the wrong word: she didn’t see these women’s vaginas; she saw their vulvas. So often, we don’t teach young women what their body parts are called, failing to even name their vulvas, a practice that erases female body parts, pleasure, and sexuality. By choosing to use this language, Pappas misses an opportunity to empower her readers and offer them knowledge and tools to understand their own bodies.

I want to be clear that I resonated with Bravey; it is honest and inspiring. It allowed me to see and understand the work Pappas’s book is trying to do: bring light to mental illness in sport; empower girls and women and teach them to appreciate their bodies; write openly about things that are hard to discuss. Pappas gets close to these goals, and sometimes she nails it, like when she talks about how she finally realized the strength of seeking help for mental illness rather than trying to handle everything on her own, or when she came to the understanding that her “rules” about “always being a team player” or “sleeping with a guy just because she went back to his dorm room” or “only being satisfied when she pushed herself to complete exhaustion” were not serving her and needed to change, or when she finds a supportive partner who helps her continue to grow and learn and try new things. But handling those issues well makes the issues that aren’t handled well more noticeable.

And despite my critiques, I’m on Alexi Pappas’s team. I admire her deeply and I empathize with her struggles. I want her work to succeed because the work she’s trying to do is the work I’m trying to do. I, too, want to give these uncomfortable discussions airtime, reduce stigma, empower women in athletics, open my sometimes-very-closed self to the world. Pappas has done a great job of starting these conversations, and her growing, devoted social media following of young, strong, impressionable “Braveys” is evidence of that. But on behalf of this captive audience, I also think she can do better. We can all do better. That’s what moving this work forward means. That’s what being Brave is.

Kate Raphael is a writer living in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her recent work appears in LeapsMag, Bon Appetit, and the Tracksmith Journal.

Talk about this article and Bravey on the LetsRun.com messageboard. MB: Guest Column on Alexi Pappas’ Memoir Bravey: How Bravey Could Have Been Braver

Are you interested in publishing a guest column on LetsRun, email us.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available 24 hours a day at 800-273-8255.