Q&A: Anti-Doping Expert Sergei Iljukov Discusses Doping in Kenya & Russia, What World Athletics Is Doing Right — And How the Global Anti-Doping System Can Still Improve

By Jonathan Gault

May 12, 2020

In February, a team at the University of Helsinki led by anti-doping expert Sergei Iljukov conducted a WADA-funded study examining women’s middle distance performances at the Russian track & field championships from 2008 to 2017. The aim was to examine the impact of the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP), which was introduced in 2009, so Iljukov and his team compared results from 2008 to 2012 against results from 2013 to 2017 (at which point the ABP had been fully implemented and athletes were used to seeing others sanctioned for ABP violations). The Russian championships were chosen as a meet to study because Russian athletes draw salaries from their cities, counties, or ministry of sports based on their results at nationals. And of course, because it is well-known that many Russian women were cheating in the late 2000s/early 2010s.

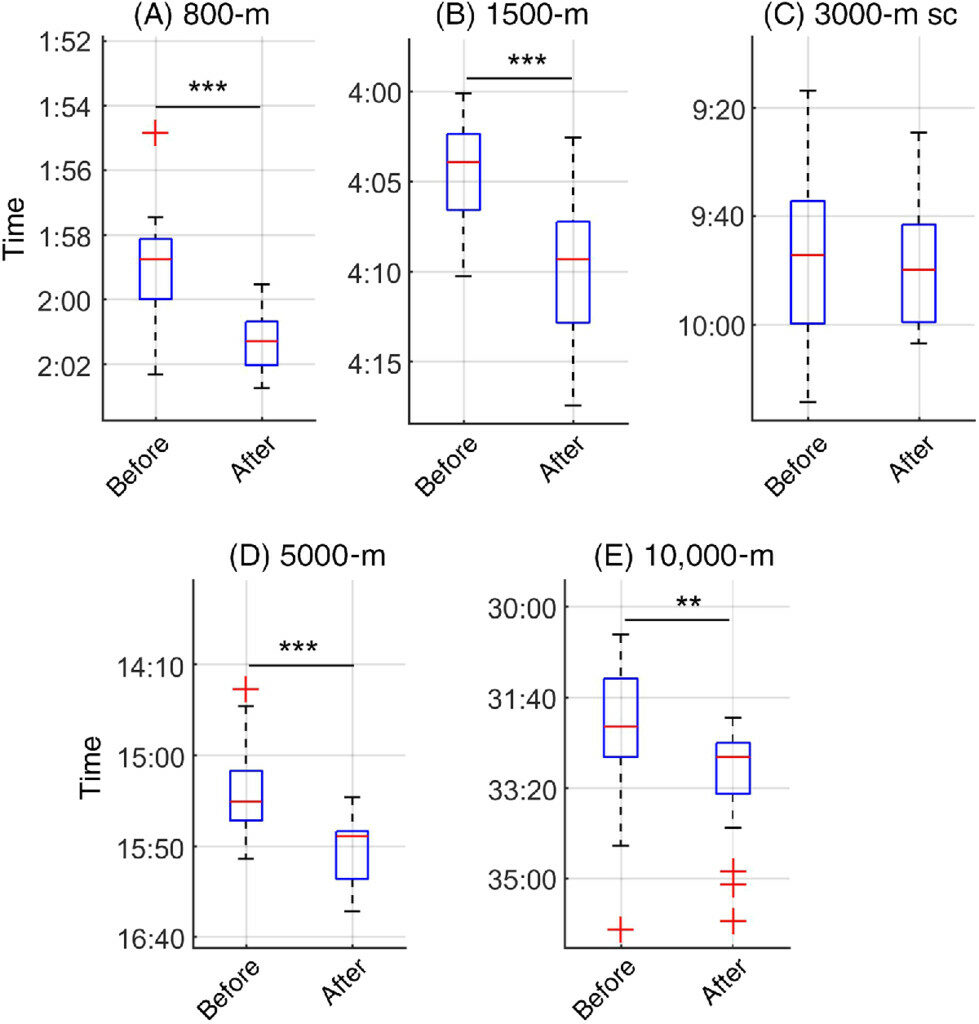

The results were clear: performances were significantly worse in the second half of the decade studied than the first. This, in itself, was not shocking, but for Iljukov, the degree of difference was: in every event minus the steeple (which was only introduced to the Olympics in 2008), performances dropped between 2.0% and 3.4% — in line with the results of old Soviet studies examining the effects of blood doping on elite athletes.

Iljukov, 40, who was born in the Soviet Union, raised in Estonia (he served as medical advisor at the Estonian Anti-Doping Agency for almost a decade), and now lives in Finland, is continuing to study how performance profiling can be used to improve anti-doping efforts around the world. Last week, he took some time to talk to LetsRun.com about deficiencies in the global anti-doping system, whether the culture has changed in Russian track & field, and the effects of the ABP in Kenya.

JG: You told me before this interview you believe World Athletics is doing a great job with anti-doping. Why do you believe that?

SI: There was a study from Daegu 2011 that demonstrated the prevalence of doping may reach up to 40%. And on the other side, people are saying from the annual reports of most anti-doping agencies, you can read that only 2% of the samples test positive.

When we talk about those 2%, which are misleading, we don’t quite appreciate the fact that we have to relate the number of those findings to the number of athletes tested. As just a simple mathematical example, you have 10 different elite athletes in your registered testing pool. And you test each of those athletes 10 times a year. Altogether, you get 100 tests. And from those 100 tests, you have two positive samples. That basically means two out of 10 athletes have tested positive. Officially in statistics, you only have 2% of all the tests positive. But if you take it from the testing pool, you have 20% of athletes. So that makes a huge difference. It’s important to deal with this in mind, that those statistics are misleading.

So we have to look deeper at the registered testing pool, the number of the athletes, and they must be related between each other. So it’s quite a big job to do for the anti-doping agency and I think that [is the] explanation [for] why it is still expressed as an absolute percentage from all the tests.

And also, when we estimate the prevalence, like it was done in the studies before…you have a sort of methodology to test how many athletes possibly use substances in that particular competition. But that doesn’t tell you how many athletes from the whole population use substances during their whole career.

And basically, what our study demonstrates, based on those banned athletes, that in some distances, it’s up to 68% of the athletes who are banned during their career (Editor’s note. 13 of the 19 — or 68% — of Russian women who achieved the world/Olympic/Euro 1500 standard at the Russian champs from 2008 to 2012 were ultimately banned. For all distance events collectively, the figure was 53%). So that’s quite a high number. And based on that, I can definitely say the question, is who [caught] them? First and foremost, it’s an international federation (World Athletics) and this we have submitted and I will give some compliments to their job. And also, definitely the national anti-doping agency was also involved. So those are two institutions.

These numbers, they tell you a little bit more than those widely finding 2%. And your question was why I think World Athletics is doing [a] great job with anti-doping. So this is basically an example. You take a long-term scale, 10 years. And you take a look during this 10 years, how many athletes have tested positive. It better reflects the anti-doping efficiency in the long term.

But there’s a tradeoff though. If you’re looking over a 10-year period, and someone’s been cheating for eight years and you only catch them after the eighth year, do you think they’re still doing a good job because they’re catching them eventually? Or do you think it’s bad because they’ve allowed them to cheat for who knows how long?

That’s a good question. You never know when the athlete is cheating. And the question is also when he started cheating and when did you get him and so on. So it’s difficult to answer the question. I fully agree and I don’t want to bring the picture that anti-doping is brilliant or something like that. But also you hear more of critics. And based on this data, certainly there is a place for compliments. This is basically my point.

To get back to the study that you had [of athletes at Russian nationals] — did the results surprise you at all?

Well there was one surprise to me. From all Soviet studies, it was known an approximate effect of blood transfusions on performance. And what I was surprised to see [was] very close numbers [to that] in our study. Because we basically indirectly estimated the effect of blood doping on performance. And this is also, from the practical point of view, quite important. Because when you have a, let’s say, 800m elite-level female athlete who is improving her performance from her average, all of a sudden — let’s say three seconds or 2.5 seconds — you see a sort of red flag. Because that sort of improvement doesn’t happen within a short period of time. It should take a much longer time. And those estimates were very close to what was known from the old Soviet studies. So that was a sort of surprise to me.

But why would that surprise you? If your study is estimating the effects of doping, why would you be surprised that it would be in line with a study that had already shown that was the effect of doping?

Well because I didn’t expect to get it from these numbers and I didn’t expect it to be so close. So that was surprising to me.

Do you think there are inefficiencies in the current global anti-doping system? And if so, how would you propose to fix them?

To be honest, yes, definitely there are some deficiencies. Just to be in balance, to say all the pros and cons.

But if you think of the inefficiencies, the general topic of our research is about performance profiling. We are trying to identify some unphysiological performances and trying to look for the possible explanation — what could be there. And this study is just part of the job.

When you go deeper into details, [there is] one thing I see as a sort of discrepancy currently. How would you define elite athletes? What would be your definition?

I would say certainly athletes who compete at a World Championship, you would say they’re elite. Or maybe the top 100 in each event in the world.

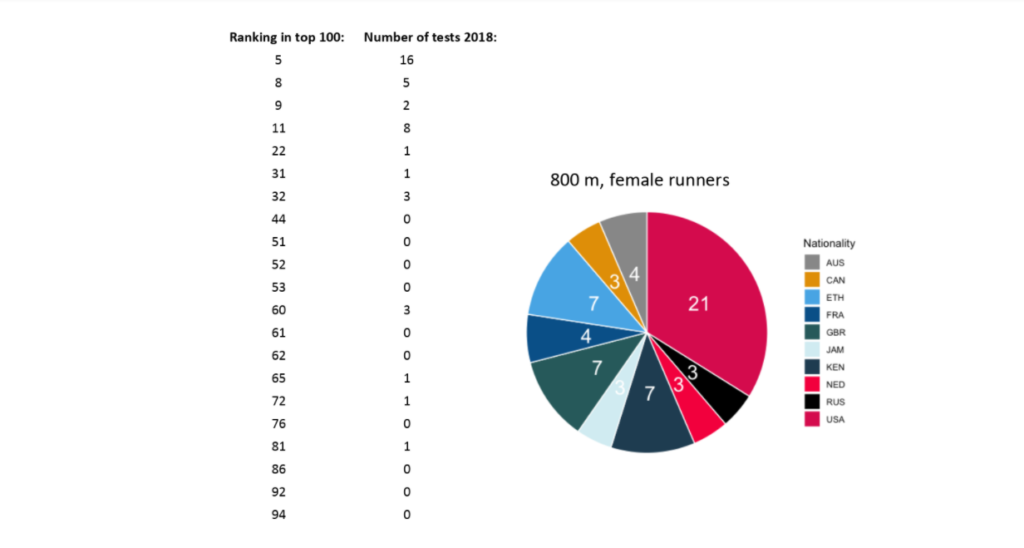

Brilliant. You study from the performance level he is competing in. It makes sense. [Let’s take female] 800m athletes who run faster than 2:02. Let’s call them elite athletes. You can see there are athletes from more than 20 countries who are running these times. But if you take a closer look, you can see there are 21 athletes out of all those athletes — the dominating group — they’re coming from the US. And if you go and look at the stats from USADA, only the top of those athletes are tested properly. And many of them who are competing on the NCAA level, they are not tested as rigorously by USADA.

For example, you take an athlete from Sweden or Finland who is running under 2:02, she will be [tested] on the Athlete Biological Passport. But in US, the situation is different. There is a discrepancy.

I’m bringing this fact not to blame USADA, because they are doing a great job, you can see it from the statistics. But there is a deficiency in the current definition of elite athlete. There is an insufficient description of the elite athlete and who you must have to put in the registered testing pool. Because in the current situation, you have, as I told you, athletes from Sweden who will be rigorously tested when she’s running around 2:00. And from some other country, where you have 10 athletes at that level, half of them will be as rigorously tested. So in this sense, we are in a situation where the anti-doping makes a difference.

I wouldn’t like to stress that it’s a particular country, like the US, because if you go in the longer distances, you can see some from African countries. It’s not the problem of the country itself. It’s the problem of the current definition of the registered testing pool and elite athletes, who we are testing. So that’s the deficiency, to be honest.

So what’s your solution to this? Would you want them to standardize the definition across the globe?

Yes. For sure. Please don’t take my words as blaming. It’s not the fault of any anti-doping organization or it’s not the fault of any particular country. But it’s the deficiency of the current approach. As a scientist, you analyze the data. You see the facts. You do conclusions and you have to raise the awareness and you have to establish your opinion based on the facts. So probably this is a good place to start talking about this, based on the facts.

How would you suggest using the performance data to improve catching cheaters?

Well this is the topic we are currently working on. Those are preliminary results, and further research is necessary. But I guess in future, in some sports where the metrics are quite simple like in athletics, or swimming, weightlifting, sports like that, you probably could improve efficiency of targeting some athletes based on their suspicious results. But also the research is necessary to define what is suspicious and what is not and so on. So we have to be very careful in that sense. And once again, it’s never only about the performance itself.

I wish to stress — and put bold on this sentence — excellent performance, in itself, is not the proof of any wrongdoing. That’s very important to stress. You do not throw a shadow on athletes based on their performance. That would be wrong.

I feel like the anti-doping agencies are already doing this (target testing). Like if you look at someone like Justin Gatlin, he’s an outlier in terms of his performances versus his age. I feel like anti-doping agencies are kind of already target-testing athletes who they feel have suspicious performances, even if the performance isn’t necessarily backed up by data the same degree as yours is. Do you know what I’m saying?

Yes. It’s quite logical. As I told previously, doping is used to improve your performance. But it doesn’t help if you apply it in one country only and if there is no general policy that is applied in all the countries, because our study is funded by WADA, so there is a strong interest over that. And it’s going in this direction. This will give you one more dimension when you evaluate and assess.

What do you think about the current anti-doping situation in Russia? Do you believe the culture has changed or that it is changing?

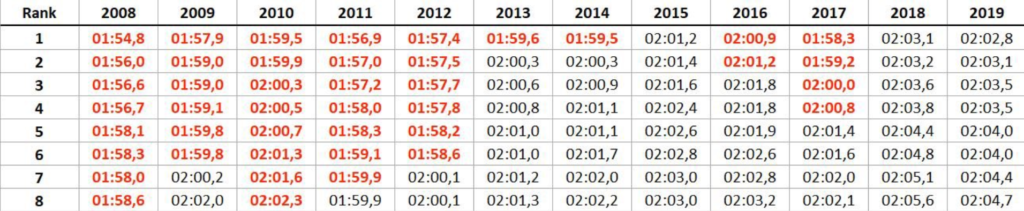

I sent you the picture with Russian results [from their national championships]. This is, once again, about the 800m females. It’s very similar in 1500m, 5000m, 10000m.

You can see from this data, the red performances, that means in a particular year, this is the number of athletes who qualified for the international competition of this particular year (Euros, Worlds, Olympics) with their results at the nationals. And you can see there is a significant drop after 2012. There is an obvious explanation why: the ABP.

You can see the next year, over the years, the level of the performance drops significantly. When you ask me about the culture, I have my doubts that the culture is changing within a couple of years. But what I can say is that the ABP set a sort of threshold — what you can do and how you can cheat and what you cannot do. And here you see this change. They cannot use blood doping in the same amounts that was possible before the ABP, and that makes a huge difference.

And so when you ask me about the culture, to be honest, I don’t think that the people who were involved in that sorts of practices before 2013, they suddenly change their mind and their approach and so on. But, as I told you, it’s not about the changing of the culture, it’s about opportunities, what sort of drugs you can use and you cannot. There is change happening there.

I want to ask about Kenya. Because we’ve seen several ABP violations from Kenyan athletes recently, since the start of 2019. In part, that’s because they now have a WADA-accredited lab in Nairobi. But one explanation I’ve heard is that it’s possible the ABP, they may have to adjust it, or they’re not totally sure about it for Kenyans because they were born, they were raised, they’re training at altitude. Altitude has been known to throw off the ABP a little bit. And it might be hard to use the same parameters as you would for a traditional athlete than you would for a Kenyan athlete using the ABP. Do you think there’s anything to this theory? Have you heard this theory at all?

If I answer this question from the performance perspective and from the anti-doping perspective, as you told, the Nairobi laboratory was established, as far as I know, they started in August 2018. And when you start implementing the ABP, [it takes time] — because in Moscow, they started somewhere in 2009, 2011 [and] you can see the results only starting from 2013. And the reason for that, when you start your ABP, first of all you have to define the group, the registered testing pool. Then you start collecting the samples. And you have to have at least three samples to establish the baseline.

Once you have the baseline, you continue the follow-up. Maybe some athletes start using banned substances after two years or three years or four years or five years. You never know. So because of that, you can see that when you start a new anti-doping measure or policy or method, it takes time to get those athletes caught. And I think we already have some data. Actually, there are 45 [Kenyan] athletes banned since 2017, and most of them are based on nandrolone and very primitive drugs, so it’s not about sophisticated doping. But I have to admit, there are a dozen elite world-class athletes who were banned based on ABP. And I think that the top of the curve — it’s the same like with Russia — in the beginning there were some first cases, and all of a sudden you have the avalanche of cases. Because you had enough time to implement the ABP. And currently, the implementation started in 2018, but I don’t think we can see the full effects of the implementation yet.

But what I’m asking —

Yeah, about adjusting. Well, with ABP, you are familiar with how it works? The basic principles are you get the blood values and you build up an individual profile. And so this concept is equal, regardless of the country of the athletes. And there are maybe some confounding factors, and the altitude is one of them. But the effects of altitude are more moderate than effects of significant blood transfusions or EPO. In that sense, there are some challenges, but I don’t think those are the biggest challenges in anti-doping.

And also, when you check the ABP parameters, you can basically say there are some findings that are clearly suspicious and you start the discipline or the investigation. Then about some findings, you can say that they are reasonably clean, there is no suspect. And in some cases, you can say that those findings are somewhere in between. And then you’re starting to investigate the confounding factors and so on, and also if you heavily suspect and you have findings from in between that are not clearly indicating of doping use, but they also don’t look very clear, you can start targeting your testing.

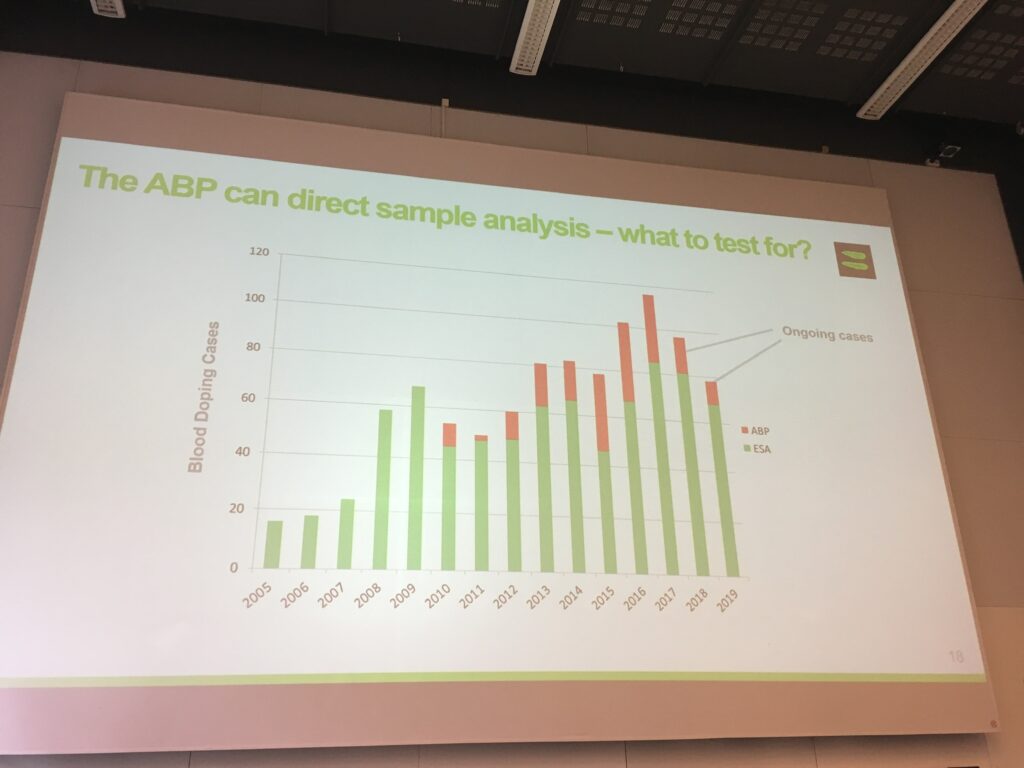

And this is actually another point of implementation of the ABP. When WADA started implementing the ABP, the number of EPO cases increased dramatically. That was astonishing.

And this is actually another point of implementation of the ABP. When WADA started implementing the ABP, the number of EPO cases increased dramatically. That was astonishing.

The green bar [in the table on the right] is so-called “ESA” — erythropoiesis-stimulating agent. Basically, those are different sorts of EPO. And the red one, ABP cases. And what you can see from here, the implementation of ABP started in 2007, 2008. And you can see the increase in ESA cases, because they were targeting based on the ABP results.

If you know the process, when you get the samples for the ABP, you take a blood sample and a urine sample. And those green cases, you may have a finding in the ABP but the same time, when you take a look at the urine, the EPO is there. You don’t need to go further with ABP findings because you already have the case in your hands.

I was going to ask more specifically about Kenya. Have you reviewed any of the cases where they have sanctioned athletes for ABP violations? Have you read over them at all? And if so, do you believe like, yeah, this person seemed like they were clearly cheating? Does it make sense to you that they were banned?

Well, I didn’t review any cases. I don’t have access as a researcher. But what I can say: the probability, when you start an investigation based on the ABP case, the probability that it’s a false positive is about 1 out 1,000. Very, very low. So basically what does it mean? If you have a case based on the ABP, the probability that it’s a true positive is over 99.9%. And also, this is the statistical probability. But you have to bear in mind that an athlete has an opportunity to defend himself. If you have a reasonable explanation for those findings, it will not be a case. So you don’t give bans based on those numbers only.

What are you studying now? What else do you want to study or think needs to be studied in the anti-doping field?

We continue with the scope and we focus currently on track & field runners, middle and long distances. And the next step will be one of the current research topics, we’re trying to establish the definitions of elite-level athletes, international-level athletics, national-level athletes, to build up a classification based on performance results. And the third aspect, and what is currently under work, is also we are, based on those previous doping cases, we are trying to build a sort of mathematical model for the changes in performance. We try to model the doping effects with performance results to build up a statistical model.

So are you doing that with data from athletes who have already been banned?

Yes, exactly. That’s all retrospective. But there are some deficiencies in this approach. And once again, because of that, I wish to stress, again, excellent performance itself is not a sign of any wrongdoing.

But at least we can see this is a promising direction for further research. And with this particular study, the major point I wanted to bring to attention is that there’s a general perception that anti-doping is inefficient. You can hear a lot of critics toward World Athletics and so on. But take a look at the numbers. You rarely hear any compliments. And in my opinion, those numbers deserve some compliments.

More: Read the Full Study. Association Between Implementation of the Athlete Biological Passport and Female Elite Runners’ Performance