From Santa Fe To Boylston Street: How American Coach Ryan Bolton, An Olympic Triathlete, Helped Caroline Rotich Win The 2015 Boston Marathon

By Jonathan Gault

May 12, 2015

The road to the Boston Marathon title is a lot longer than the 26.2 miles of Massachusetts asphalt that connect the Hopkinton Green with Boston’s Back Bay. Think of the road to the title as the world’s longest, most circuitous highway. Recent history shows us the road starts with a birth somewhere in East Africa, but the path from there to Boylston Street has far more turns than the race day route. There are a ton of exits on the highway, with drivers constantly exiting and entering. Most people never reach the end, and those that do need some help arriving.

Whether she knew it or not, Caroline Rotich had been on that road since her modest upbringing in Nyahururu, Kenya. It took her to Japan’s Sendai Ikuei Gakuen High School and eventually Santa Fe, N.M., where she was introduced to Ryan Bolton, who had traveled a long road of his own from Gillette, Wyo., to the Sydney Olympics as a triathlete before winding up in Santa Fe. On April 20, 2015, they reached their destination together: the Boston Marathon victory stand. Before they embark on their next journey, let’s look back at how this one unfolded.

Wyoming-raised

Bolton, now 42, grew up in the town of Gillette in northeastern Wyoming. The US’s least-populated state isn’t known for producing distance runners, but Bolton, an age-group star growing up, had the fortune of attending Campbell County High School, Wyoming’s dominant power in track and field/cross country. Bolton was never the best guy on his high school team. During his freshman and sophomore years, Bolton’s best friend Jason Drake (who would wind up running for and coaching under Mark Wetmore at the University of Colorado and is now an assistant at the University of Washington) was the top runner in the state. Once Drake graduated, that mantle passed to Bolton’s classmate Jim McCreery, who won the 400, 800, 1600 and 3200 at the Wyoming state meet during Bolton’s senior year in 1991 before going on to a collegiate career at Arizona State where he sits at #4 all-time at 800 at 1:48.19. Still, Bolton ran well enough in high school (4:20 1600, 9:30 3200) to earn a scholarship to college; his dream was to follow Drake to Colorado.

“I was recruited by CU when Jerry Quiller was there,” Bolton said. “I was a broke Wyoming kid and they offered me a little bit of money, but not nearly enough for me to afford it. I really wish I could have went to school there because I think I would have been on national championship teams. I wouldn’t have been standing on the starting line of NCAAs alone.”

Financial realities forced Bolton to stay in-state and he wound up at the University of Wyoming. There, Bolton ran solid PRs of 8:08 (3000) and 14:14 (5000), but it was in cross country that he really excelled.

“I think a lot of that had to do with living in Laramie, Wyoming,” Bolton said. “The summer and the fall training was absolutely fabulous and the winter training was absolutely atrocious.”

Bolton would spend his summers training with the CU men, including future Olympian Alan Culpepper. Between summers in Boulder and falls in Laramie, Bolton developed into a fine cross country runner, taking 12th as a redshirt senior at NCAAs in 1995, just two seconds back of Meb Keflezighi (a sophomore at the time). However, at 5’10” and 150 lbs., and with a 14:14 pb, he realized that his future didn’t lie in running.

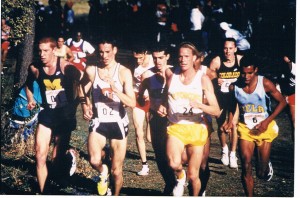

“My senior year at cross nationals, there was a picture in Track & Field News,” Bolton said. “It’s a great photo. For me, it’s kind of a badge of honor because every guy in the photo was a stud or an Olympian. There’s [Adam] Goucher and Keflezighi and I’m running side-by-side, duking it out. I look like this giant next to these guys even though I was skinny at the time.”

Before becoming an Olympic triathlete, Ryan Bolton (far right) more than held his own at NCAA XC as he got pub in TFN in 1995. Subscribe to Track and Field News – The Bible Of The Sport here.

Before becoming an Olympic triathlete, Ryan Bolton (far right) more than held his own at NCAA XC as he got pub in TFN in 1995. Subscribe to Track and Field News – The Bible Of The Sport here.

Bolton graduated from Wyoming in 1995 with a degree in exercise physiology and was working on his master’s in human nutrition the next year when the International Olympic Committee announced that triathlon would be added to the Olympic schedule for the 2000 Sydney Games. A strong swimmer and cyclist, Bolton saw his opportunity. He spoke to his graduate professors, and with their blessing put his studies on hold, relocating to Colorado, where he split his time between Boulder and the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs. Bolton was tremendously self-motivated, and when he made the Olympic team in 2000, it didn’t come as a surprise to those who knew him best.

“When he put his mind to something and got serious, he was always willing to do whatever it took to get that,” said Drake, who lived with Bolton in Boulder during that span — including when Running with the Buffaloes was being written (Bolton would occasionally hop in with the CU men for long runs or tempos). “I always particularly remember him, especially when he was trying to make an Olympic team, he was always willing to live the lifestyle and not go out, not drink, and do all those type of things. He’d always be extremely dedicated in that world, no matter what. I think he became stronger when he saw other people messing around and he was going to bed, just remembering that unwavering dedication to go to bed at 9 p.m.”

Bolton wound up 25th in Sydney and continued as a professional triathlete until retiring in 2004. Despite his success, Bolton never felt totally comfortable.

“The life of an athlete was great but I felt like I kind of wanted more,” Bolton said. “I also never felt totally in my skin as a triathlete, as a pro. I kind of grew up a runner and the fitness that you got from running and the lightness, I never felt that way as a triathlete. It’s much more of a power-oriented sport. I never felt as gazelle-like as [I did as] a runner and I never totally adapted to that. It was a different type of fitness. As a triathlete, I felt like I was powering through the air and as a runner I felt like I was floating through the air, which to me was a more natural feeling.”

He returned to Wyoming to finish up his master’s, where much of his coursework focused on human physiology and metabolism. In 2006, at the urging of his former triathlon coach Joe Friel, Bolton began to advise runners and triathletes online. His coaching career had begun.

Getting started in Santa Fe

Despite all the success triathlon brought him, Bolton’s heart belongs to running. He loves it for the purity and rawness no other sport can match. Bolton moved to Santa Fe from Laramie in 2008, where a friend of his, Matt Desmond, introduced him to Scott Robinson, an agent in charge of the AmeriKenyan Running Club in Santa Fe. Robinson asked if Bolton would be interested in helping out with some of the athletes from time to time. Bolton wanted to do more than just “help out.” He believed many of the athletes in Robinson’s group were directionless and felt that if were to work with them, he had to be all-in.

“This is their life, this is their career,” Bolton said. “You can’t just partially be helping these guys. If I’m working with a person, I need to be working with them 100 percent.”

The first person that Bolton began to work with seriously happened to be Caroline Rotich. Rotich arrived in Santa Fe in 2009 after attending Japan’s Sendai Ikuei Gakuen High School on a sports scholarship. Her path was very similar to that of the late Sammy Wanjiru, another former Sendai student who hailed from Rotich’s hometown of Nyahururu in Kenya. That is where the similarities stopped, however. While Wanjiru became a marathon sensation, winning the Olympic title at the age of 21, Rotich’s career never got off the ground. By the time she got to Santa Fe, her best pb was 33:19, run in a 10k road race in Minneapolis the previous summer. Her 1:14:40 half marathon best wouldn’t have been competitive even as a halfway split at a major marathon like London or Chicago.

Bolton sat down with Rotich and saw a raw, naïve 24-year-old. He could tell from her workouts that she had talent, but he believed Robinson was over-racing her, dragging her to small races in towns like Topeka, Kan., in search of modest paydays. Bolton asked Rotich to commit to his training plan, which would involve racing far less and putting a greater emphasis on the bigger races with significant prize money. It was a gamble on Rotich’s part, putting her faith in this self-described “mysterious mzungu” (an Swahili term referring to someone with white skin), but she agreed, and in 2009, she was the only athlete Bolton coached.

Bolton bumped her mileage significantly and his goal was for Rotich to peak late in the year for the 11.5-kilometer Obudu Ranch Mountain Race, a hilly race in Nigeria which offered almost $200,000 in prize money, including $50,000 for the win. Rotich lacked turnover but she was strong as an ox, and Bolton felt the hilly course played to her strength. The plan had to be scrapped however, after Robinson ran into problems with Rotich’s visa, frustrating Bolton. Scrambling for an alternative, Bolton tried to find a race so that her hard work wouldn’t go to waste. He settled upon the Rock ‘n’ Roll Las Vegas Marathon on December 6, which offered $15,000 for the win and another $10,000 for the Gender Challenge (first man or woman to cross the line, with the women receiving a 20-minute head start). He hadn’t planned on racing her in a marathon this soon, and though Rotich had covered the distance before, it hadn’t gone very well (she had run 2:49:47 in Nairobi three years earlier).

“Honestly, it wasn’t the best idea but it was the best to get everything we could out of her training,” Bolton said.

Nevertheless, he drew up a race plan, telling Rotich to stay relaxed over the first half of the race and not to push until the 20-mile mark — not unlike the strategy she would employ six years later in Boston. Rotich executed it to perfection. She trailed the leader by over 30 seconds at the halfway point, but chipped away at the deficit throughout the race and pulled away over the final five kilometers, winning by 18 seconds in 2:29:47. That was good enough to win the Gender Challenge too, netting her a cool $25,000.

After reuniting with Bolton in the finish area, Rotich grabbed her coach and told him, “I’m training under you, and I trust you and I believe in you.” They’ve been together ever since.

“A lot of people always tell me, ‘How can someone who didn’t run [professionally] know how to coach another to run and think you’re going to run well?'” Rotich said. “And I always go with, it’s a choice. It’s what you know you want to do. Choosing him as my coach, I know he knows what [he’s doing] and since I started training with him I see every time I’m getting better and better.”

The Harambee Project

In 2010, Bolton began working with two more Robinson athletes: Haron Lagat and Aron Rono, a pair of Kenyans who had gone through the American collegiate system (Lagat at Texas Tech, Rono at Azusa Pacific). But the Bolton-Robinson relationship had become strained, largely because the two still disagreed on how many races their athletes should be running. Later that year, Bolton sat down with Robinson and told him that he could not work with him anymore. He left Robinson and the AmeriKenyan Running Club and asked the three athletes that he had developed relationships with — Rotich, Lagat and Rono — to come with him. All three put their faith in Bolton.

Robinson, who began representing athletes in 2006 and also works as the branch manager of Gateway Mortgage Group in Santa Fe, admitted that in that point in his career, he may have over-raced some of his athletes.

“I would say that at the time I was relatively inexperienced in athlete management,” Robinson said. “I entered it more from a service aspect to assist these athletes to get visas and help them to get travel to go to different races. I guess part of it was me being naïve. Sometimes the athletes would want to go to more races than obviously they should have been going to. I’ve since learned from [Bolton’s] input and input of other coaches to not let the athlete control the schedule so much as the coach because the coach knows [them] a lot better.”

Using his income from his online coaching service, Bolton rented a house for the runners in Santa Fe and bought a beat-up eggshell-white 2000 Toyota Sienna that had around 200,000 miles on it as a team car. The smell of sweaty runners quickly came to permeate every inch of the interior. The Nike Oregon Project this was not. But Bolton was happy.

“It was a dream of mine to get this group going and getting some solid runners in,” Bolton said. “I was really interested in dealing with runners who wanted to be world-beaters…There’s no place I’d rather be at 8 a.m. Monday morning than at a track workout with these guys.”

The name of his group, the Harambee Project, comes from a Swahili term he often heard Rotich use.

“Right when I started working with Caro (as Bolton calls her), one topic that we talked about was it would be nice to train with other people,” Bolton said. “Her first year she trained alone a lot. She would always talk about, and I would hear the other Africans talking about, harambee (pronounced huh-RAHM-bay). What makes the Kenyans good? Caro would say, ‘Harambee.’ I was like, ‘What’s that?’ She’s like, ‘Training together.’ It’s a Swahili term that in general means ‘together, as a team, we achieve more,’ and I was like, ‘Sweet, I like the word harambee, what a neat name for a group.’ That’s what we’re accomplishing. Whether there are Americans in this group or Ethiopians or Kenyans, we’ll call it the Harambee Project and that’s kind of the name we’ve kept with it.”

Bolton couldn’t offer much, but he started talking to agents and slowly but surely, his group began to grow. Rotich managed a seventh-place finish at the New York City Marathon in 2010 while Lagat became a fixture as a rabbit on the Diamond League circuit, getting down to 8:15 in the steeple by 2011. Rono smashed his 10,000 pb by running 27:31 in 2011, but frustrated by his inability to secure a sponsorship despite hitting the World Championship ‘A’ standard, left the group in 2012 to join the army and become a U.S. citizen.

Since 2010, the group has changed in composition, with athletes coming in and out. Two-time World Cross Country champ Emily Chebet will train with Bolton in Santa Fe from time to time, as will 2:06 marathoner Peter Kirui, who won the NYC Half in 2012. Even the two constants, Rotich and Lagat, aren’t in Santa Fe year-round, as Rotich likes to return to Kenya after her fall season while Lagat spends most of his time in Lubbock with his fiancée where he’s a volunteer assistant coach at Texas Tech or in Europe during the Diamond League season.

Bolton, who lives in Santa Fe with his girlfriend, Tracey, and her two children, Liliana (8) and Adri (5), says he still derives the vast majority of his income from offering his coaching services online to runners and triathletes through Training Bible Coaching. He also said he receives a small cut from athletes such as Rotich and Lagat, but that alone is not enough to support himself. His main goal is to one day have the funding to be able to attract 10-12 world-class athletes to his group in Santa Fe. That dream is far closer to reality than it was five years ago. With Rotich, Lagat and Wichita State grad Aliphine Tuliamuk-Bolton (no relation), he has a nice core and Rotich’s win in Boston has lent him credibility. In the weeks since her victory, he’s been approached by scores of agents with athletes looking to join his group. Bolton even upgraded the team vehicle, surprising his runners at a recent practice with at 2007 Toyota Highlander after trading in the Sienna.

Planning for Boston

Rotich’s victory in Boston on April 20 surprised many people, but Bolton was not among them. He saw the progress she had been making over the past few years — 4th in Boston in 2011 after running 68:52 to win the NYC Half, 4th in Chicago in a PR of 2:23:22 in 2012, a win in Prague in 2013 and 4th at another World Marathon Major in Tokyo in 2014 — and knew that one day soon, she would be ready to win a major. Bolton felt that Rotich was too inexperienced to win Boston in her first go-round in 2011, and in subsequent majors felt she wasn’t quite ready to respond to the critical move. Over the past few years, he’s re-engineered her training to allow Rotich to respond to those moves late in a race, and even make a few of her own.

Rotich’s 2015 buildup started poorly. After running 2:27:32 for 4th in Yokohama last fall, she returned to Kenya for November and December to spend time with her family. Unlike many athletes who go to Kenya to put in heavy training, Rotich follows a light schedule when she is at home. Bolton prefers to have his athletes under close supervision, but recognizes that it’s important to recharge the batteries after a long year of training. He doesn’t expect Rotich to return to Santa Fe in tip-top shape, but has made it clear that she must be at a certain level of fitness so that they can get to work stateside.

When Rotich reported back to Santa Fe in early January, Bolton could tell right away she was behind schedule. While in Kenya, she had gotten sick, battling typhoid and malaria, and her early workouts in Santa Fe went poorly. Bolton knew that any margin for error he had in her Boston preparation had been eliminated. Rotich was scheduled to run the NYC Half as a tune-up race on March 15, but with only two weeks to go until that race, Bolton was sitting on his couch, wringing his hands about whether to let her race.

“She just wasn’t quite where she needed to be yet,” Bolton said.

A couple of days later, Rotich hit a work out, and gave Bolton a look that told him “I’m back.” From there, it was game on. Rotich finished fourth in NYC in 69:53, and the final five weeks of her Boston prep went perfectly.

The Anatomy of a Victory

“In my opinion, in Boston the racing doesn’t really start — the people who are truly going to win the race — until after the hills,” Bolton said.

That principle guided Rotich’s race-day strategy and heavily influenced her buildup during the first four months of 2015.

Part I: The Beginning (Start to mile 16)

Boston is an up-and-down course, but the first 16 miles of the race are primarily downhill or flat. It is only once the runners cross the Charles River and head from Wellesley into Newton that the uphills begin to get serious. With that in mind, Bolton prescribed a steady diet of 100+ mile weeks to ensure Rotich had the strength to get through the first 16 miles attached to the lead pack.

Bolton said he told Rotich before Boston: “You’re really fit and I know you can finish really strong. You need to just tuck in and conserve as much energy as you possibly can. Let everyone else do the work. Pay very close attention to the race. If there are significant moves by significant people, you need to cover those moves. Get through the first 21k, get through the first 25k basically by being as conservative as possible.”

A group of 11 women made it through 25k (15.5 miles) together, after passing halfway in 72:44-45. Though her name was barely mentioned on the race broadcast, Caroline Rotich was one of them.

Part II: The Newton Hills (mile 16 to mile 21)

It takes a different kind of strength to successfully navigate the Newton Hills, a five-mile stretch in which the net elevation gain approaches 200 feet. Santa Fe is ideally suited for developing that strength, as the town sits at 7,000 feet of elevation and is surrounded by rolling hills that can climb several thousand feet. By running there almost every day, Rotich calloused her legs for the undulations of the Boston course and built the mental toughness required to hang onto the pack.

“25-35k (15.5 to 21.8 miles), I told her, ‘You need to be very alert because that’s where moves are going to start happening,'” Bolton said. “But I told her, ‘I don’t want you to be aggressive and I do not want you to initiate anything at that point yet.’ Because once again, I was pretty confident in her fitness and her finishing fitness.”

By the time the lead women crested Heartbreak Hill and headed to Boston College, the pack was down to nine. Rotich was still there, biding her time.

Part III: The Downhills (mile 21 to mile 25)

The day Bolton knew Rotich could win the Boston Marathon came 16 days before the actual race. It was Rotich’s last long run with intensity, and they had made the 64-mile drive from Santa Fe to Albuquerque, as they did twice a week to escape Santa Fe’s elevation for Rotich’s more intense sessions.

“Santa Fe is a great place for strength work, but it’s hard to get speed,” Bolton said. “[In] Albuquerque we can get to 5,000 feet or lower.”

For this run, they headed to Albuquerque’s Paseo del Bosque Trail, a dirt path which runs along the Rio Grande through the western side of the city. The goal of the workout was to practice accelerating on tired legs — something Rotich had struggled with in her previous major marathons but would need to master if she were to win Boston.

The workout was as follows:

3-mile warmup

1 mile at 100-105 percent of goal marathon pace* (5:15)

2 miles at 85-90 percent of goal marathon pace (12:00 – 6 minutes/mile)

1 mile at 100-105 percent of goal marathon pace (5:15)

5 miles at 7:00 pace

1 mile at 100-105 percent of goal marathon pace (5:12)

2 miles at 85-90 percent of goal marathon pace (12:00 6 minutes/mile)

1 mile at 100-105 percent of goal marathon pace (4:58)

1-mile cooldown

*Goal marathon pace for Rotich was 5:20/mile; her actual splits are given in parentheses

“[Through the first half of the workout], she was spot on,” said Bolton, who was following along on his bike. “I’m like, okay, it’s early in the workout, she looks good.”

Rotich crushed the second half of the workout. She ran her final mile — her 16th mile of a workout run at 5,000 feet of elevation — in 4:58.

“You went under 5:00 on that last mile, you were feeling good?” Bolton said.

“Yeah, yeah, I felt great,” Rotich responded.

“You’re ready to go,” he told her.

Sure enough, when Mare Dibaba threw in a 5:07 24th mile to break up the pack in Boston, Rotich was ready. She and Buzunesh Deba were the only runners to counter the move, and as they headed into Kenmore Square, the lead pack was down to three. In addition to the workout above, Bolton said he had prepared Rotich for Boston by handing her several workouts where she was to work hard on uphill segments before really opening it up on the downhills that followed. Those hours spent on the roads and trails of New Mexico had paid dividends. Now Rotich was a mile away from becoming Boston Marathon champion.

Part IV: The Finish (mile 25 to finish)

To win in a kick, a runner requires two things: the mental belief that they are going to win the race and the physical ability to maintain their form as fatigue hits their body. Bolton and Rotich have been hard at work on both for several years.

“I’m a huge believer in doing a lot of neuromuscular work,” Bolton said “There are a lot of times on easy days or even longer run days where we’ll do short interval work late in the workout with a lot of recovery to work on good mechanics at high speed and also good mechanics on tired legs.”

Sure enough, Boston came down to a kick. By the final turn onto Boylston Street, Rotich and Dibaba had dropped Deba. With 200 meters to go, Dibaba had opened up a gap, but Rotich’s form never broke. She kept pumping her arms and legs vigorously, and when she pulled even and eventually passed with Dibaba with 100 to go, her Ethiopian rival grimaced while Rotich wore a smile on her face. Yes, while the flaws in Dibaba’s stride became exaggerated — her head tilting to the right, her stride rate slowing — Rotich’s was actually smiling, her stride becoming more powerful with every step. Two hours, twenty-four minutes and fifty-five seconds after she started in Hopkinton — and six-plus years after meeting Bolton — Rotich was the winner of the Boston Marathon.

“If you look at Caro the last 300 meters of the Boston Marathon, that wasn’t coincidence,” Bolton said. “I was watching her, and in her head, I could see [her thinking] ‘Drive the arms, drive the legs.’ This is exactly what we’re doing in practice…A lot of people have said she looked so powerful at the end and I said it’s because for months and years, we’ve been practicing that because that’s what it takes.”

It’s easy to give in when every part of your body is screaming at you to let go, but in that final mile, Rotich never stopped competing.

Rotich said as she turned on to Boylston Street, “I was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to be sick.’ But just like that, I saw the finish line and I was like ‘I can kick.'”

Video of Final Stretch at Boston:

Ultimately her faith in herself, and in the kick she had worked so hard to develop, carried her to the title. Bolton feels that belief may have been the missing piece in past marathons.

“This year, I just think she went into the race with a confidence and a calm I’ve never seen from her before,” Bolton said. “She was confident with her training and knew exactly how to execute…to her, this wasn’t a surprise.”

Before the race, two of Rotich’s friends, Caroline Kilel and Sharon Cherop, both former Boston champs, had joked with her that they had both had a turn and now it was Rotich’s turn to win. Neither knew how true those words would become.

What’s next?

Rotich’s Boston journey is over, but another one is just beginning. Bolton and his athlete haven’t mapped out a specific plan, but now that Rotich has tasted victory on the sport’s biggest stage, she wants to keep winning — at major marathons, at the World Championships, at the Olympics.

According to RunBlogRun, Rotich hopes to one day become an American citizen, but when exactly that might happen (if at all) is unclear. Bolton didn’t know of any such plans (the two haven’t discussed it), and maintained that Rotich loves Kenya and is proud to represent her homeland.

In fact, there’s no place Rotich would rather be than Kenya, but that’s something that’s just not feasible at the moment. Her Boston win has brought an onslaught of media requests and obligations, and once she gets through those, it will be time to start another training cycle. Rotich also just signed a shoe deal with Mizuno USA (she previously had a deal with Mizuno Japan, but that expired prior to Boston even though she ran the race in Mizuno apparel). But she will return to Kenya in November once her fall season wraps up, and this time, she may have company.

“I’ve told [all my athletes], as soon as one of you wins a major, I’ll go to Kenya and hang out for a while,” Bolton said.

Bolton’s first trip to Kenya to celebrate Rotich’s win would only be appropriate. For Rotich to celebrate in a manner befitting her Boston triumph, she needs to have as many family and friends back home as possible. After all, as a member of the Harambee Project, she knows more than anyone, “together, we achieve more.”