How To Turn Pro In Track & Field, Part I: Finding an Agent

By Jonathan Gault

January 22, 2020

Sponsorship contracts are one of the most secretive things in the sport of track & field. Basic details such as their value and length, widely available in major professional sports such as football or basketball, are hidden behind the walls of nondisclosure agreements.

Track & field doesn’t have a draft, and there are no age limits: athletes are free to sign a contract whenever they please. So how does a sponsorhip deal come about? LetsRun.com decided to investigate.

This week, we’ll take you behind the scenes of the transition from collegiate athlete to professional, from finding an agent to signing a contract to case studies of two of the top athletes from the college class of 2019. After interviews with over two dozen athletes, coaches, agents, and shoe company executives, here’s your three-part guide to how to turn pro in track & field.

Part I of the series is below.

Part II is here: How To Turn Pro In Track & Field, Part II: Signing the Shoe Contract

Part III is here: How To Turn Pro In Track & Field, Part III: Case Studies of Grant Fisher and Morgan McDonald.

When Charles Jock lined up for the first round of the men’s 800 meters at the 2012 U.S. Olympic Trials at Hayward Field, he wore the same diamond studs in his ears as he had two weeks earlier when he won the NCAA title in Des Moines. He wore the same chain around his neck. But there were two significant differences.

On his feet, instead of the blue and white Asics JP Swords he had worn at NCAAs, he sported a pair of black Nike Maxcats. And on his torso, Jock had traded in the faded gold and navy singlet of the University of California-Irvine for a Nike professional kit, gray over black with neon piping and a white swoosh over his left breast.

This is how most of the track & field world found out that Charles Jock had signed with Nike.

Before the rise of social media, this sort of “announcement” was common. Athlete wins NCAAs. Athlete shows up at USAs in a pro kit. Somewhere in between, one deduces, a contract was signed.

It still happens. In 2018, NCAA 800 champ Isaiah Harris ran the first round of USAs in a Penn State singlet, saying after the race he was still deciding whether to turn pro. When Harris showed up for the final in a Nike kit, his decision was clear.

But the transition from collegiate to professional athlete is far more complicated than trading laundry. Take Jock, for example. When he woke up on the morning of Monday, June 18, 2012, a day after walking at graduation with a degree in urban planning, he was convinced he would end the day as an Asics athlete.

It seemed a natural fit: Asics sponsored Jock’s UC Irvine team, and their US headquarters were a 15-minute drive from campus. Jock had a meeting at Asics HQ that day.

Jock had already received a preliminary contract offer prior to the meeting. He was happy with the base salary, and though he wanted Asics to come up a little when it came to medical and travel stipends, he was confident that his agent Chris Layne, who had flown in for the meeting, could negotiate a deal.

“I was happy with it,” Jock says. “I would have taken it if we talked numbers.”

During the course of the roughly three-hour meeting, however, Jock says that never happened. Mostly, the discussion focused on his future as an Asics athlete — how they would market him, new shoes they were developing, a potential pro group. Even though he had not yet officially put pen to paper.

“I think at the time, the person that was doing the negotiations for Asics kind of just assumed I was going to sign with them,” Jock says.

But Jock wanted to sign a contract, and he wanted to sign it as soon as possible. His flight to Eugene for the Trials was leaving on Tuesday, and UC-Irvine had declined to pay for the trip. Jock wanted to ink a deal before his first race on Friday so that he wouldn’t have to foot the bill for his travel expenses.

Asics’ failure to act left the door open for other suitors. That night, as Jock pondered his options, Nike came in with an offer. The base salary was substantially higher than what Asics had offered, and the medical/travel stipends were larger. And Nike meant business: they told Jock that the offer came with a hard deadline.

Tuesday morning, as he was traveling to Eugene, Jock told Layne he was going with Nike. He signed the contract that night, and by Wednesday, his room at the Eugene Hilton was filled with 30 boxes of Nike shoes, clothes, and gear — so much that he couldn’t fit it all in his suitcases when he left. And that’s how Jock, who was only 8th at the 2012 Trials but would go on to make the Olympics in 2016, became a Nike athlete.

***Everyone’s Situation Is Different

Though the number of American athletes turning pro out of high school is rising, the overwhelming majority still come through the NCAA system. Jock’s transition from collegiate to professional track & field athlete was not typical, but that implies that there is a typical experience. Some athletes, like Grant Fisher, a two-time Foot Locker Cross Country champion, are on the radars of agents and shoe companies from the moment they step on campus.

At times, the scouting process moves at warp speed because of a fundamental truth of track & field: the clock doesn’t lie.

Last year, LSU freshman Sha’Carri Richardson went from top college sprinter to one of the most sought-after runners in the world after running a collegiate record of 10.75 (#9 all-time) in the NCAA 100-meter final. Junior Sinclaire Johnson of Oklahoma State, who had never even made an NCAA final before 2019, lopped over four seconds off her personal best by running 4:05 to win the NCAA 1500-meter title. Within 30 minutes of crossing the finish line, she was approached by an agent who wanted to know if Johnson was interested in turning professional. Both Richardson and Johnson wound up signing with Nike.

For many potential pros, this process — the transition from running collegiately to signing with a shoe company — is shrouded in mystery. For example: How much did Matthew Centrowitz make last year? When does Jenny Simpson‘s New Balance contract expire? How big was Donavan Brazier‘s bonus for winning Worlds? You can spend all day googling, but you won’t find anything. Only a handful of people on the planet that know the answers to those questions, and most, if not all, are bound by non-disclosure agreements.

“Through the process, I felt like I was just learning as I went…I didn’t feel at all insecure about my lack of knowledge because there just wasn’t a lot of conversation about it in general,” says Abbey Cooper (née D’Agostino), a seven-time NCAA champion at Dartmouth who signed with New Balance out of college in 2014.

D’Agostino learned about the process the same way most athletes do: by talking to agents. Which means that the recruiting process is part sales pitch, part explainer course: Pro Track & Field 101.

“I’ve noticed a lot that the agent who gets in first, the first one who gets a real conversation with an athlete, that’s a big part of it,” says agent Dan Lilot, whose clients include Dathan Ritzenhein, Moh Ahmed, and Gabriela DeBues-Stafford. “Because maybe, for whatever reason, you are now associated in that athlete’s mind with everything and you’re the one who maybe explained things to them.”

“Going through your first contract, agents have so much power because you don’t know what you’re worth,” Jock says. “You can look up what LeBron James is getting paid by the Lakers. You can look up what kind of contract Tom Brady just signed. But you have no idea what [track athletes] make.”

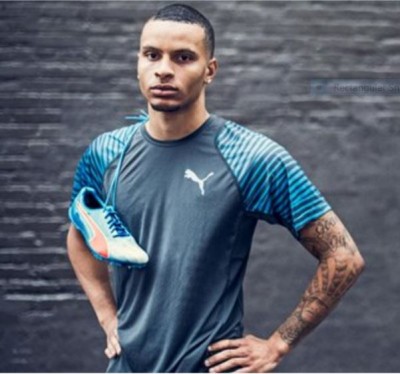

A rare exception came in 2015, when Canadian sprinter Andre De Grasse signed with Puma. Though full details (including the contract’s length) weren’t published, his agent Paul Doyle told The Canadian Press that the deal was worth roughly $11.25 million, with $4 million guaranteed and bonuses that could push it to $30 million.

Doyle says he’d like to see more deals become public.

“I honestly don’t know why it’s kept such a secret,” Doyle says. “…I think maybe it’s been set from years ago that we didn’t want to release track numbers because they’re very unimpressive. And nowadays the numbers are getting more impressive, so I think a lot of companies should consider releasing the figures.”

However, Doyle also says some uncomfortable truths could be revealed if all athlete contracts were made public.

“People would see the disparity between the haves and the have-nots for sure,” Doyle says. “There is a huge amount of discrepancy. When Andre De Grasse signed his deal, he was a 9.92 100-meter runner and you’ve got other guys that are 9.99 100-meter runners that aren’t getting a dollar.”

***You Don’t Have To Be A Huge Star To Get An Agent

Shortly after UMass’ Heather MacLean stepped off the track after finishing 6th in her preliminary heat of the 800 meters at the 2018 USATF Outdoor Championships in Des Moines, she left the athlete warmup area and began to walk toward Drake Stadium’s main grandstand. That’s when the UMass logo on her jacket caught the eye of a man who had competed for the Minutemen as a decathlete in the ’90s. He approached MacLean and struck up a conversation, and while she appreciated his enthusiasm, she wasn’t quite sure what to make of him. She thought he might be a UMass superfan. Had he flown all the way to Des Moines just to watch her race?

Not quite. The man was Paul Doyle, one of the most powerful agents in the sport — in addition to De Grasse, he reps world champions Christian Taylor and Sam Kendricks.

MacLean had made the NCAA mile final in 2016, but she had struggled to recapture that form, battling pneumonia for most of her senior year. She graduated with good but not great PRs of 2:03 and 4:19 in the 800 and 1500 meters, but wasn’t sure how long she would continue in the sport — or how to go about doing so.

“I literally didn’t know what an agent was until this agent at NCAAs approached me to talk to me,” MacLean says. “I was like, wait, that’s how people get pro contracts? They have agents?”

Meeting Doyle felt like fate, and the two sat down in the bleachers to chat. MacLean told him that she would be in Greece that summer for an assistant professorship. He told her that he could look into getting her into some European meets while she was over there.

“Fifteen minutes later, I was her agent,” Doyle says.

For most athletes, hiring an agent is step one in turning professional — though most agent-athlete courtships last longer than that of MacLean, who finished 7th at USAs in the 1500 in 2019 and now runs for New Balance Boston. For a fee — the industry standard is 15% of an athlete’s earnings — agents negotiate contracts, book travel, enter athletes into meets, and, in general, look after the athlete’s interests.

***Are Agents Worth 15%?

Is it worth it? That depends on who you talk to.

“I think they make you that [15%] back if you have a good agent and they can be the one to deal with the hard stuff,” says Dathan Ritzenhein, entering his 16th year as a professional.

“For better or worse, you need an agent, period, full stop,” says Nick Symmonds, a strong advocate for athletes’ rights who won six US 800-meter titles and retired in 2017. “If you don’t have an agent, just don’t even try. I know that sounds really bad, and I wish it wasn’t the case. But the shoe companies don’t want to deal with your parents. They don’t want to deal with you. They don’t want to deal with your uncle or your lawyer. They want to deal with about five people in the entire sport.”

One NCAA coach, who requested anonymity, draws issue with the 15% fee.

“This whole agent system is archaic and doesn’t make any sense and should not exist the way it exists,” the coach said. “If an agent has a kid he signs at $300,000 and a kid he signs at $150,000 and a kid he signs at $75,000, the bonuses are basically all the same: if you win a medal, you get $100,000. That’s all fine. Does he work harder for the kid at $300,000 than he does for the kid at $75,000? Because if that’s true, the $75,000 kid should never sign with him because he gets 25% effort. But if the agent says, no, I work equally hard for all my athletes, then why do you charge this guy four times more than this guy? Because you’re doing the same job.”

Former 800-meter runner Phoebe Wright puts it more simply.

“15% is highway robbery for what they do,” Wright says.

Danny Mackey, head coach of the Seattle-based Brooks Beasts professional team, said that, in his experience, agents can’t do much to change the base value of a contract.

“With us, or any company for that matter, an agent’s not gonna come in and get this crazy deal; agents do not have that power, the individual athlete does,” Mackey says. “Brooks is gonna be like, this is what it is, this is what we’re gonna offer you. We have a very firm process set up in place based on the athlete’s potential.”

“A big misconception is that someone is going to get a significantly better deal with one agent versus the other,” says Lilot. “The general outline of any deal is based on the athlete’s performance and potential.”

But Mackey does believe that a good agent can make a difference when it comes to negotiating things like medical stipends, bonus structures, and option years.

“The fringe stuff, that’s where agents can be really helpful,” Mackey says.

The vast majority of top athletes — i.e. the ones with serious contracts as opposed to the ones pursuing it as an expensive hobby — elect to sign with an agent. There are a few notable exceptions. Emma Coburn and Jenny Simpson represent themselves, and because both have been among the top in the world in their events for several years, they never have a problem getting into a meet (Simpson was initially represented by Ray Flynn and began representing herself in 2015).

Stanford’s Vanessa Fraser elected not to use an agent when she turned professional in the summer of 2018. Fraser had planned on hiring one, but often, the process of finding an agent and finding a sponsor/training group plays out simultaneously. She reached a decision on her professional destination — Nike’s Bowerman Track Club — before deciding on an agent, and at that point, Fraser had a choice: negotiate her own deal, or hire an agent and trust that they’d be able to boost her contract by 15%. Fraser chose option 1, though there wasn’t any negotiating; knowing she wanted to be with Bowerman, she agreed to Nike’s first offer and didn’t even look at offers from other companies.

“[Going without an agent] is not something that I necessarily would advocate for or recommend. However, I do feel like for my particular situation it’s worked out fine and quite well,” Fraser says. “…I have no doubt that an agent could have produced probably more money, but it’s impossible to know how much more.”

For those athletes who don’t have the luxury of picking and choosing which meets they want to run, an agent can be crucial. Getting into a Diamond League — or even a second-tier meet in Europe — can be a cutthroat process. Though it’s far easier today for an athlete to reach out to a meet on their own than in the pre-internet days, you’re more likely to get into a big race if you’re represented by someone who has a relationship with the meet director (Fraser said one of the reasons she felt comfortable without an agent was that her coach, Jerry Schumacher, holds sway with meet directors). In some cases, the meet director is an agent.

Two years later, MacLean is glad she found Doyle. She ran two European races in June 2019, dropping her PR from 4:14 to 4:10 at a race in Chorzow, Poland, and then to 4:06 in Ostrava, Czech Republic. Those performances eventually led to her receiving an invite to the Birmingham Diamond League in August. MacLean, who finished 7th at USAs last year, says that without an agent, there is no way she would have been able to pursue those races, which showed everyone — including herself — her true potential.

***The Process Is Starting Earlier and Earlier

Most agents have a list of prospects they’re constantly updating and typically make first contact with a top prospect before an athlete’s senior year. That initial meeting is often just a quick hello at a track meet to put a face to a name, rather than a formal sitdown. Once an athlete hits their senior year, the recruiting process gets serious.

To secure a top talent, it’s vital to reach out early. Until 2017, Hawi Keflezighi‘s clients — including Meb Keflezighi (his brother), Leo Manzano, and Joe Kovacs — consisted solely of veteran athletes. That year, he went to the NCAA Outdoor Championships to recruit his first crop of college athletes. He quickly realized that he had missed the boat; most of his targets had been talking to other suitors for months.

“That timeline has really escalated,” says University of North Carolina coach Chris Miltenberg. “…Those vetting conversations are already happening [before NCAAs], whereas I think as much as five years ago, none of that was happening until the Monday morning after the NCAA meet — or at least with the people that I had.”

Let’s clear up a misconception: there is no rule prohibiting agents from approaching athletes — or vice versa — before their eligibility is complete.

“Athletes are a little bit afraid initially because they’ve been so preprogrammed to think that talking to agents is a bad thing and it’s not allowed,” Doyle says. “And that’s absolutely not true.”

“I feel like a lot of times it’s portrayed to look like the agent is the bad guy,” says agent Stephen Haas of Total Sports. “And that’s certainly not the way we feel…There’s aspects of this job [where] you really help people out. You’re helping them find out what is going to be the best situation for them, you’re helping them find the best coach for them, you’re helping them negotiate the best contract for them. Those are the things that I think are forgotten about and everybody just has this misconception that an agent is just someone trying to get in on your earnings.”

There are rules that an athlete must follow to preserve their NCAA eligibility, and the NCAA encourages athletes to inform their school’s compliance officer if they’re considering starting the professional process. Athletes cannot signal an intent to professionalize, which means they can’t verbally commit to an agent or shoe company, nor can they discuss specific contract dollar values before their eligibility is up. The latter provision can be especially difficult for an underclassman unsure of their value who is deciding whether to leave school early, considering the lack of publicly available athlete salary data.

These rules aren’t always followed. Before NCAAs, it’s not uncommon for an athlete to let agents know, with a wink and a nod, which agency they’ve decided to sign with.

“I had one athlete tell me before, they said ‘I’ve been considering three agents and I’ve eliminated two of them and you’re still in there,'” Doyle says.

And while no agent interviewed for this story was willing to admit they had ever discussed specific contract values with an athlete before their eligibility expired, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen.

“If you are baiting an athlete to come out of school because an agent has a deal for them, I think that’s a violation,” says Flynn, whose clients include Ajee’ Wilson and Molly Huddle. “Has it happened in the past? Probably. I’m sure it has. In fact, I know it has. But that doesn’t mean it’s happening all the time. Like anything in life, there are abuses.”

Another problem: the turnaround from amateur to professional athlete is quick. Imagine a college basketball player competing at the Final Four and then joining a team for the NBA playoffs two weeks later.

“NCAAs happen and there’s a two-week period, sometimes less, before they’re getting on the starting line at USAs,” says Jesse Williams, who spent over a decade as the head of sports marketing at Brooks before leaving in 2017. “So that means they need to pick an agent, go through all their options, sign with a brand, get all of their gear, put an announcement out, get pictures taken, and then get out on that starting line.”

Doyle also says that, prior to NCAAs, he’ll hear from professional meet directors looking to fill lanes for upcoming meets.

“I put it out there and say, listen, I might be representing this person or I might not, but if I do end up being the agent I’d love for them to come to your meet, that sort of thing,” Doyle says.

2020 will be even more hectic than usual. The NCAA Championships conclude on June 13 in Austin; the US Olympic Trials begin just six days later in Eugene. And in an Olympic year, there is more pressure than usual to get a deal done before the Trials — brands want athletes in their jerseys at the Trials, and athletes want the contract bonuses that come with making an Olympic team.

“That’s not enough time, [less than] two weeks, to make a decision about what you’re gonna do the next several years of your life,” says Ben Rosario, head coach of the HOKA ONE ONE Northern Arizona Elite professional team. “I would like them to be treated like mature adults. There’s no reason that once you get into your senior year, once you have less than, let’s say, six months to go until your eligibility’s complete, that you can’t start talking finances with a potential employer. I mean, every other student on campus can. All these rules were based on football and basketball because the money is so huge, and they don’t want corruption and they don’t want agents coming in and giving them cars and upfront payments of $50,000, blah blah blah. First of all, that stuff happens anyway. Second of all, it’s apples and oranges. Each sport is different and each sport should be treated differently.”

Once an agent decides to start recruiting an athlete, they must jump through some hoops. That starts with getting registered. Some schools’ compliance departments require agents to fill out forms before speaking with an athlete. Each state has its own requirements, as well. To speak to an athlete at a school in California, it costs $30 to register with the state. In Georgia, it’s $200. The strictest law is in Texas, which requires $500 and a $50,000 surety bond.

***The Role Of The College Coach

Once everything is in order, an agent can reach out to an athlete, typically through their college coach, who acts as a buffer until the athlete is ready to start vetting agents. When that process begins depends on the specific coach and athlete.

During his 13 years at the University of Oregon, Andy Powell, now the head coach at Washington, coached numerous future pros. His preference was to hold off discussions with agents until after an athlete’s collegiate season. Powell says that 17-time NCAA champion Edward Cheserek didn’t have any serious discussions with agents until after his eligibility had concluded. When Matthew Centrowitz went professional in 2011, he waited until after the World Championships, where he earned a surprise bronze medal, before starting talks with agents.

“That’s probably why he did so well, because we didn’t really have any other thoughts,” Powell says. “…Enjoy the moment and don’t rush it. I’ve seen athletes, whether it’s the hype of media or their coach or interviews, or maybe just the pressure of themselves, who maybe don’t enjoy their senior year or perform as well as they could have because they’re thinking about all this other stuff. Chances are, if you run fast, it’s all gonna work out.”

Miltenberg and Fisher took a periodized approach during Fisher’s final year at Stanford. Fisher met with several agents and coaches after the cross country season to narrow his list down early before making his final decision in the spring.

“Instead of putting these things off, [we said] let’s have these conversations during December, when things are a little quieter,” Miltenberg says.

Coaches at top-tier programs go through this process on a near-annual basis, but each athlete only goes through it once. Miltenberg believes he has a duty to educate his athletes on the post-collegiate landscape, but tries not to exert his opinion; ultimately, he says, the decision must come from the athlete.

There’s another reason coaches prefer agent/athlete communication run through them: protection.

“I think it’s my role to protect athletes from predatory people,” says Oklahoma State coach Dave Smith. “And I think there’s predatory people in this business, whether it’s coaches or agents or whoever…There was one particular agent this year who contacted one of my former athletes about one of my current athletes and said Hey, I’m contacting you because I’m not a Dave Smith guy, don’t tell him. Just get this other athlete to contact me right away, I’m interested. That kind of behavior, to me, is slimy and unethical.”

Once an agent is registered and makes contact with the coach, the recruitment process begins in earnest, often with a phone call from agent to athlete. In the case of a high-priority target, an agent may fly out for an on-campus visit. For the agent, it’s a chance to pitch their agency to the athlete. For athletes, it’s a chance to ask questions before making a career-defining decision. The athlete’s college coach or parents will sometimes sit in on these meetings too.

“Most of what we do [in these meetings] is just answer questions of how professional running works,” says Haas. “The people who are set up the best when they graduate are the people who’ve done the most homework.”

Of course, only one agent can sign each athlete. One of Haas’s first recruits was Cam Levins, the star distance runner for Southern Utah. During Levins’ senior year, Haas followed him across the country, from the Millrose Games in New York City to the Summit League Indoor Championships in Fort Wayne, Ind. He felt they had established a good relationship. Then Levins elected to sign with Ray Flynn.

“It felt like you were being rejected almost,” Haas says.

Since then, Haas says, he has grown a thicker skin, but it always hurts to lose a client. Doyle likens it to being dumped by a girlfriend. Lilot prefers a “kick in the nuts.” But usually, there are no hard feelings. It’s a business, after all, and if you’re an agent, chances are you’ll run into that athlete somewhere down the road. They may even be looking for a new agent.

Part II is here: How To Turn Pro In Track & Field, Part II: Signing the Shoe Contract

Part III is here: How To Turn Pro In Track & Field, Part III: Case Studies of Grant Fisher and Morgan McDonald.

If you enjoyed this article, we imagine you’ll love the following series we did in 2018: LRC Pro Runners’ Salaries: How Much Do Professional Runners Make? We Unveil One of The Sport’s Biggest Secrets.

Talk about the series on our fan forum / messageboard. MB: LRC Investigates: How To Turn Pro In Track & Field.