Kenyan Distance Running Part I: Kenya, the Land of Opportunity

by Weldon Johnson

March, 2007

First off, my apologies for not sharing more of my impressions of my incredible trip to Kenya and the World Cross Country Championships. I talked about the crazy, incredible crowds at the race and have shared hundreds of my photos from my travels to the training camps after the race, but I haven’t put to words many of my experiences. And I feel until you go to Kenya and experience first hand the running scene, you don’t fully comprehend the Kenyan running phenomenon.

Running in Kenya is by and large about one thing: money opportunity. I could switch the word opportunity with the word money, but in the West that would imply greed. And most people in Kenya trying to run are often very poor especially by Western standards, but they are trying to improve their lot financially and they see running as their one shot to make a lot of cash in their lives.

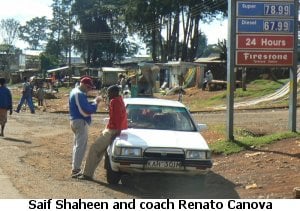

In my post- world championship travels I spent the majority of my time in the 30 mile area between the city of Eldoret (200,000) and the small running town of Iten. And I saw hundreds of runners trying to run  professionally. Some were world champions, like Saif Shaheen, and some were guys you’ve never heard of who will never race outside of Kenya. But to all of them running represented an opportunity they should not pass up.

professionally. Some were world champions, like Saif Shaheen, and some were guys you’ve never heard of who will never race outside of Kenya. But to all of them running represented an opportunity they should not pass up.

In Eldoret, I went to the track one day and met a university student. He had only recently started running and talked of running professionally or getting a scholarship to the United States. He had run 2:08. That is 2:08 for 800m, not the marathon. I was shocked that this guy who had just started running, and by objective standards was not very good (this coming from a guy who only ran 2:06 for 800 in high school), talked of running professionally. In some ways, I thought he was delusional but in some ways it was refreshing to see the Kenyan confidence in running. If this kid thought he could be a star, no wonder so many Kenyans ended up being world beaters, they all believed it is possible.

Many Runners are Wealthy in Kenya, While 58% of Kenyans Live on Less Than $2 a Day

All around in the Iten and Eldoret area, there are quite a few wealthy people who had made their wealth from running (all the money for the runners is creating a boom economy in Eldoret) In America, generally (apart from the stars), there is not a lot of money in running. Most college grads are probably sacrificing something financially to pursue their running dreams after college. But in Kenya there is relatively a lot of money in running, and most runners are after this pot of gold.

The average income per person in Kenya is around a $1000 a year. $1000 a year is nothing, but many people live on much less than that. For in reality there are almost two Kenyas, the rural undeveloped Kenya which is barely part of the cash economy where most things are on a small scale – the farms, the stores, etc. – and the developed Kenya of Nairobi where some people receive Western salaries. According to this site and this one, 58% of Kenyans live on less than $2 a day. As Stephen Biwott, brother of two time Boston champ Robert Cheruiyot said, “When you are employed in Kenya, there is no money”.

It is from the rural part of Kenya in the highlands that most of the great Kenyan runners come. In America and the West, when we think of Kenyan runners, we think of them being spread out all throughout the country, but perhaps in reality we should call them Kalenjin runners, as 3/4 of Kenya’s top runners are Kalenjin, which represents only 10% of the Kenyan population. So in essence, what you see in Kenya is that by and large there are a ton of runners or potential runners concentrated in a very small area. I counted 54 runners on the dirt track in tiny Iten one day in the morning and heard that over a hundred is more often the norm. (There are 2 surfaced tracks in all of Kenya, so those of you who think a surfaced track is necessary to train, think again.)

There is little drawback to trying to be a professional runner especially if you can  catch on with a training group and get your meals covered. If the alternative to training full-time is to make a $1 a day, many people are willing to give training full time a shot. Or they are willing to train for part of the day. In Kenya,

catch on with a training group and get your meals covered. If the alternative to training full-time is to make a $1 a day, many people are willing to give training full time a shot. Or they are willing to train for part of the day. In Kenya,

one thing you quickly learn is that time is not very valuable, hence the concept of “Kenya time” where a lot of things run late. When you are trying to eke out $1 or $2 a day, time is not of the essence. Even in very small towns like Iten, there are hundreds of people walking around, making the streets of the little village look like parts of New York City because saving money is much more important than saving time.

Financial Pressures = Short Term Success?

The financial opportunities available through running, whether it be $20,000 at the end of the year or even $1000, help explain why many Kenyan runners are only around the top of the sport for a short time. After going to Kenya, it is much easier to see why at some $250 road race on the East Coast you are likely to see a Kenyan show up. In the past, I wondered how it could be profitable. Now I see some of these guys will be content to go back home with a very small amount of money at the end of the summer. The money and financial incentives definitely affect how many of the Kenyans train in a couple of ways.

First, the chance to make a lot of money leads most Kenyan runners to train by and large for the short term. Training a couple of years down the road may make sense for a lot of people in the West, but in Kenya where you may be dropped from your group if you do not produce results, this long term approach often is not a possibility. Who can take the chance of looking two years down the road, when the opportunity to make say perhaps ten years of wages ($5000), is immediately before you? When the average life expectancy at birth is 47.5 years and living is often a grind day to day, long term thinking is often rightfully not a priority. This leads to overtraining and overracing.

The same incentive to train all-out in the short term (which I would call overtraining) presents itself to guys trying to catch on with a training group. A runner needs to make an immediate quick impression and most likely running relaxed is not the way to do this. One day after going to the track in Iten, Kimbia’s Godfrey Kiprotich remarked, “Some of the guys were training extra hard for the mzungu (white person) today.” I asked him what he meant, and he said some of the guys on the track assumed I was an agent and were trying to make a positive impression.

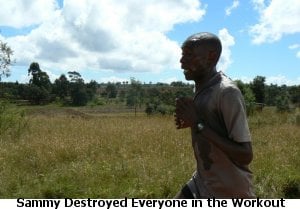

Throughout Kenya, it seemed there were a ton of guys trying to catch on. It was fairly easy to tell some of the stars apart because they trained in the new shoes, the new Nike half tights. But following them on the track might be a slew of  guys in older T-shirts and older shoes. One day I watched a workout of Sammy Nyangincha, who was training full time to try to win the $10,000 first place prize for the top masters runner at Boston. Sammy is 44 years old, but in good shape (people thought he was in around 2:16 shape but he ran poorly at Boston). So the workout is about to start, and there is one other guy in Sammy’s group, and then three other guys I have never seen before. These other guys are probably friends of friends but they are trying to catch on and get in a good workout and hopefully get an opportunity down the road.

guys in older T-shirts and older shoes. One day I watched a workout of Sammy Nyangincha, who was training full time to try to win the $10,000 first place prize for the top masters runner at Boston. Sammy is 44 years old, but in good shape (people thought he was in around 2:16 shape but he ran poorly at Boston). So the workout is about to start, and there is one other guy in Sammy’s group, and then three other guys I have never seen before. These other guys are probably friends of friends but they are trying to catch on and get in a good workout and hopefully get an opportunity down the road.

The workout was 5*3k with 2k harder and 1k easier, so a fartlek type of workout. Sammy absolutely destroyed everyone in the workout. The other guys trying to do the workout did not try to do the workout on their own terms which would be best for them long term. They tried to stay with Sammy on each interval. As a result, most of them were seen jogging home after the second and third interval (of five) as they could not keep up. Getting destroyed like this is not the best way to train for a number of reasons, but it is my impression on how a lot of guys train in Kenya. Who can afford to take a long term approach?

The financial side of running also comes into play once a runner gets fairly successful. Once a runner starts to show some promise, agents are immediately in competition for the runner. While in Iten and Eldoret, I heard numerous discussions about young runners switching agents and quickly saw that the financial side of things is big business not only for the runners but also for the agents.

Huge financial success in any society can lead to distractions and that definitely is the case with runners in Kenya. Often the names of runners who were stars in the last couple of years would come up. I was amazed at how often the talk would be about how they weren’t focused anymore, were neglecting their training, or perhaps thought the training was easy and were willing to switch to a new coach forgetting what had gotten them to the top – a lot of hard training and perhaps a good coach. It’s not hard to see how a guy who has been making $500 a year and all of a sudden has $30,000 could easily get distracted and these distractions could prevent him from attaining success in the future.

In a similar vein, I understood how if the same runner absolutely killed himself every single day for his one shot at fame and fortune, that he might be a little bit burned out, and thus just be at the top for a very brief period. American and Western runners often get nice endorsement contracts, but for many Kenyans the money often only comes in for performance. This pressure and need to compete many times in a season can lead to very short careers.

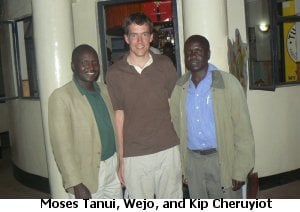

The long term success stories in Kenya, the Paul Tergats, even the Robert Cheruiyots, seem to be the exception to the rule. Cheruiyot is now the top marathoner in the world, having won two straight Boston marathons, with a LaSalle Bank Chicago Marathon in between, to go along with his Boston title in 2003. Cheruiyot’s story is one of the greatest in sport because he came from total abject poverty and his situation shows the financial incentives and pressure many Kenyan runners face. He has been homeless, lived basically as an indentured servant, and lived on 30 cents a day. Now he is a multimillionaire. For more on Cheruiyot read this incredible Boston Globe profile and Rojo’s editorial on him. But Cheruiyot almost never got his chance at stardom, even after he had overcome his dire circumstances to get in a training group run by Kenyan marathon star Moses Tanui. His coach wanted Cheruyiot out of the group because he thought he was more interested in eating than running and was not showing enough progress. Fortunately, Tanui intervened and decreed that Cheruiyot stayed in the group. The rest is history, but no doubt there are a few other Robert Cheruiyots who may never get their chance.

The long term success stories in Kenya, the Paul Tergats, even the Robert Cheruiyots, seem to be the exception to the rule. Cheruiyot is now the top marathoner in the world, having won two straight Boston marathons, with a LaSalle Bank Chicago Marathon in between, to go along with his Boston title in 2003. Cheruiyot’s story is one of the greatest in sport because he came from total abject poverty and his situation shows the financial incentives and pressure many Kenyan runners face. He has been homeless, lived basically as an indentured servant, and lived on 30 cents a day. Now he is a multimillionaire. For more on Cheruiyot read this incredible Boston Globe profile and Rojo’s editorial on him. But Cheruiyot almost never got his chance at stardom, even after he had overcome his dire circumstances to get in a training group run by Kenyan marathon star Moses Tanui. His coach wanted Cheruyiot out of the group because he thought he was more interested in eating than running and was not showing enough progress. Fortunately, Tanui intervened and decreed that Cheruiyot stayed in the group. The rest is history, but no doubt there are a few other Robert Cheruiyots who may never get their chance.

I think it is hard to understand the Kenyan running phenomenon until you go to Kenya and witness the country first hand. Iten would be my place to start if you get the opportunity.

Weldon Johnson, aka Wejo, has run 28:06 for 10k. A lady killer, he wrote his award winning senior thesis on Female Labor Force Participation in 1880. Have a question for Wejo? Email him at weldonjohnson@letsrun.com.