Trayvon Bromell Is Back; Hoping That This Comeback Will Be His Last

By Jonathan Gault

January 24, 2020

BOSTON — June 2016. That’s when it all started to go wrong for Trayvon Bromell.

Back then, life was good. Just 20 years old, Bromell had already run 9.84 for 100 meters, had already medalled in the 100 at the World Championships, had already won World Indoor gold over 60 meters. In that moment, no sprinter had a brighter future.

Then, while warming up for his Diamond League opener in Birmingham, England, Bromell felt some sharpness in his left heel while practicing accelerations. He withdrew from the meet and flew home to the United States, where an x-ray revealed a bone spur growing in his left heel, near his Achilles.

With the Olympic Trials less than a month away, surgery wasn’t an option. Bromell elected to keep racing, even though he’d still feel the bone spur jabbing into his Achilles whenever he sprinted.

“We were just like, shoot, take some Tylenol or something and try to run through it,” Bromell says.

It worked, at first. Bromell tied his PR with a 9.84 at the Trials. But three races in two days at the Olympics in Rio took their toll on Bromell, and though he made the final, he finished last in 10.06. Five days later, he left the track in a wheelchair after gutting through the anchor leg of the 4×100 relay (the US finished third but was DQ’d for an illegal pass).

Since that night in Brazil, Trayvon Bromell has raced three times.

***

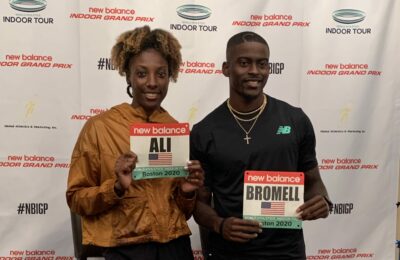

Bromell, 24, is entered in the 60 meters at tomorrow’s New Balance Indoor Grand Prix in Boston. It’s his first race under a roof since he won World Indoor gold in 2016, and he’s taking things slowly. Just crossing the finish line, he says, would constitute a success.

Bromell, 24, is entered in the 60 meters at tomorrow’s New Balance Indoor Grand Prix in Boston. It’s his first race under a roof since he won World Indoor gold in 2016, and he’s taking things slowly. Just crossing the finish line, he says, would constitute a success.

That’s a new mindset for Bromell. Like any sprinter, he wants to do things fast. But over the last few years, whenever he got healthy enough to start running again, he’d get excited and overstress his body — usually his adductors, muscles in the hips and thighs that he didn’t use much outside of sprinting — and the cycle would start anew.

“I was forcing myself to try to run fast just so I could get back to you all, and I would hurt myself more,” Bromell says. “So that’s why it’s taken me so long to get here. Because once I feel good, mentally, I think ‘Tray, you can run 9.8 now,’ and then I get another injury.”

Elite sprinters’ bodies are like Formula 1 cars. They move so fast, with so much force, that any minor weakness or imbalance is magnified and exposed. But repairing an Achilles tendon isn’t the same as swapping in a new tire. The recovery process has to be managed carefully, and even then, there’s no guarantee that the body will be as strong as before.

Often, one injury is all it takes to derail a sprinter’s career. Just ask 2011 100m world champion Yohan Blake, who has never been the same since tearing his hamstring in 2014 (Blake’s pb is 9.69 but he hasn’t run faster than 9.90 since 2014), or 400m world record holder Wayde van Niekerk, who has raced just once since tearing his ACL in October 2017.

Bromell’s path to recovery did not start smoothly. He says the doctor who performed surgery to repair his Achilles after the 2016 Olympics didn’t understand he was dealing with someone who made a living trying to run as fast as possible.

“I think he treated it as like I was just a normal guy he just wanted to get back walking,” Bromell says.

So Bromell didn’t do any sort of rehab exercises for six months post-surgery, during which time a significant amount of scar tissue built up on his Achilles. That made it much harder for him when it finally came time to return to the track in 2017, which he did at the USATF Outdoor Championships. Bromell was eliminated in the first round, running 10.22 in his prelim, and knew that his body still wasn’t right. He asked another doctor to examine his Achilles.

“He was like, ‘You know your Achilles is scarred down to your heelbone; I’m surprised that your Achilles didn’t rupture when you ran the prelims,'” Bromell says.

Bromell had a second surgery to clean and restructure the tendon, and wound up missing the 2018 season because of it. He finally returned to racing in 2019, but the results — his 10.54 season’s best ranked him tied for 285th in the US last year — showed him that he has a long way to go.

***

Bromell admits that he’s thought about quitting the sport more than once over the past four years. His past has motivated him to keep going. Bromell grew up on the south side of St. Petersburg, Fla., and is proud that he’s been able to build a better life for himself through running. He didn’t want that life to slip away just because he was injured.

“If I come all the way up here,” Bromell says, raising his hand, “and drop back here, my first instinct is, I’m going back there (St. Petersburg). And nobody wants to be back there, because it’s bad there.”

Bromell used two of his passions, music and photography, to help him work through the frustrations of his seemingly neverending injury cycle.

“With photography, I was able to create an environment for other people to see their happiness,” Bromell says. “With music, it was therapeutic for me because I was able to get my emotions out. Because I really don’t talk to a lot of people about things like that… I make music that’s very emotional and very heart-feeling. I don’t make club bangers. I don’t make music people play at parties. I make music people feel in their soul when they may be going through a hard time because I want to preach to the world that you’re not the only one. Because I remember I used to feel like that.”

Bromell says he has an EP in the works with four or five of his most emotional songs that he’s planning on dropping when the time is right — ideally, once he’s back to racing at a high level.

***

Once the brightest young light in US sprinting, Bromell has been thrown into the shadows as Christian Coleman and Noah Lyles have risen to the top of the sport. That’s okay with him; Bromell is happy to toil in relative anonymity as he works his way back.

“I don’t really look at fame or nothing like that,” he says. “I like going to the store and not being noticed.”

Bromell has been based in Jacksonville under coach Rana Reider since last summer, where he trains with a group that includes Olympic medalists Andre De Grasse, Omar McLeod, and Nia Ali. He says it feels like being on a team again, and enjoys training with De Grasse, whom he’s raced against since his college days.

“It’s like a brotherhood,” Bromell says. “If you [saw] it when we [were] in college, everybody tried to make it a rivalry, but I tried to get Andre to come to Baylor before he went to USC. It’s all love.”

Under Reider, Bromell is trying to build strength, lifting more than in the past, and says he hasn’t felt any pain in his Achilles since joining the group. Bromell says his body is feeling good again, that he’s ready to go as he wheels out of the garage for his first time down the straightaway in 2020.

But he has had this feeling before and it has ended badly. More than anything, he’s working on being more patient, trying to remember the long road laid out ahead of him — even if it goes against his nature.

“You can’t just take a brand new car off the lot and rev the engine. So you’ve gotta take it through its phases. We’re going to see where my body is at and we’re gonna keep progressing…I’ve seen what happens when I try to get out and just try to go.”