Recommended Read: Dr. Michael Joyner Reviews Matthew Futterman’s Running to the Edge

By Michael J. Joyner

July 2, 2019

Running to the Edge: A Band of Misfits and the Guru Who Unlocked the Secrets of Speed

by Matthew Futterman, published 2019

Running to the Edge is an excellent new book and interesting read by Matthew Futterman that uses the stories of coach Bob Larsen, the Jamul Toads, Meb Keflezighi, and Deena Kastor to highlight some of the recent history of distance running in the U.S. Interspersed in the narrative are enjoyable vignettes from Mr. Futterman’s experiences as a committed recreational marathoner. I enjoyed reading the book and enthusiastically recommend it.

The first two-thirds of the book covers where the Jamul Toads, an outstanding distance running club from San Diego, came from. It also tells the story of how they ultimately won the 1976 AAU Cross-Country Championships. There is also more than a bit on the decline of U.S. distance running in the later 1980s and ’90s. The last third of the book is on the roots of the more recent reemergence of at least some distance running excellence in the U.S. as exemplified by Keflezighi and Kastor. Because Bob Larsen coached the Toads and also Keflezighi and Kastor, he is the central player in the book, joined perhaps by the ghosts of Ed Mendoza (1976 Olympian and 2:10 marathoner) and Terry Cotton.

I read the book as someone who had a middle-of-the-pack view of this as a walk-on member of the University of Arizona distance running group (1977-81) and roommate of Thom Hunt, the youngest Toad from the 1976 team. I have also spent plenty of time in San Diego and the descriptions of training in the San Diego area were extremely vivid for me. Until I read the book, it had been a while since I thought about getting up every morning and running four miles with Thom – no matter what. Emphasis on no matter what.

As I thought more about the Jamul Toads part of the book, it almost became a sort of business school case study for me as I pondered one of the slides we made in my lab a few years ago on U.S. marathon times.

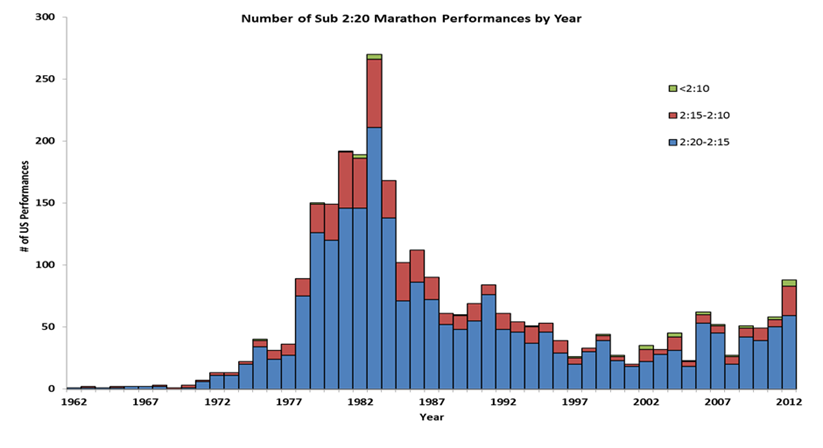

The slide is a summary of sub-2:20 marathons by U.S. men from the early 1960s through 2012. It shows a progressive rise starting in the early 1970s, which peaks in 1983 and then declines rapidly. While there has been a lot of speculation about the cause or causes of the post-1983 decline, perhaps a more interesting question, and one that the Toads part of Running to the Edge can help answer, is what led to 1983? So, here is my take in six lessons.

- Excellence does not come out of a vacuum. As a result of Roger Bannister, Billy Mills, the televised 1960s Cold War track meets with the USSR, Jim Ryun, and later Frank Shorter, interest in middle and long distance running was occasionally front-page news. The health benefits of jogging were also starting to be appreciated and promoted. So there was at least some general societal interest in the topic of elite middle and long distance running. The running boom has happened (several times) but the focus shifted to the fitness runners.

- San Diego was a “right place.” The weather and terrain in San Diego are ideal for training. The community college system in California that emerged in the early 1960s was a way for undifferentiated young people to find a way, and that was true for both academics and sports. So while there was no formal pipeline, there was a way for the generic 4:30 high school milers of the world to keep at it. The San Diego Track Club also existed, and there were some serious post-collegiate runners in the area. Zoom out, and at least some of the ecosystem that the Toads evolved from was available in many communities.

- Talent ID works. In the 1960s there was also regular fitness testing in public schools. As I read the book, I was struck by how many of the Toads were identified early on via a grade school or junior high 600-yard run test. Again, nothing formal, but the coaches talked and kids were identified, many before high school. That so many gifted runners emerged essentially from a couple of neighborhoods makes me wonder just how much wasted aerobic talent is out there.

- Incentives matter. Having a high school letter jacket was a big deal – a really big deal — to boys in the 1960s and early 1970s. It is as simple as that, and distance running was the way for the short, skinny, less athletic kids to have a chance at a letter. I wonder how many high school runners with serious aspirations are running 500 or even 1,000 miles this summer. How many are participating in the once ubiquitous high-quality all-comers meets on a weekly basis?

- Tribes. The Toads were clearly a tribe. I was part of one in Tucson and versions of them existed all over the country. Among other things, there was built in accountability, always someone to train with, and always someone to pick up the pace and push the last half of a standard 8-10 mile run. Typically there was a place to meet every Sunday morning for a 15-20 mile run. It is hard to run 90-100 miles per week or more, but much easier if it is simply baked into your peer group. Typically there were a few “old guys,” perhaps in their later 20s, or even in their 30s, who were still running fast and served as guides for the rest of us. Ken Young, for example, got us all running on the mountain trails around Tucson and it really helped. There were clearly fewer distractions then, but perhaps the electronic environment is only a minor part of what happened after 1983. From my perspective, it did not become pervasive until the middle 1990s.

- Bob Larsen and innovation by accretion. In the middle 1960s there were a number of “schools” of thought on the “right” way to train distance runners. Interval training, Lydiard’s approach, Cerutty-style extreme fartlek, Bowerman’s more mixed program, and some who favored ultra-high mileage. What coaches like Bob Larsen did was mix and match the best of all of these systems. Ideas, especially from Dave Costill, about early versions of what became known as the lactate threshold also confirmed the utility of what are now called “threshold” runs. My hall of fame coach Dave Murray called them “control runs.” The one thing that is inescapable though is that VOLUME MATTERS. That being said, when I compare the weekly training schedule of Eliud Kipchoge to what Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers were doing, it is hard to see that much of difference. We certainly raced all the time in the 1970s, and I wonder if that is another missing piece of the puzzle. Not enough racing.

So, when I look at the six lessons from Running to the Edge, beyond highly focused teams for elites that use the sort of training outlined in my sixth lesson (and a bit of altitude), what could be done today to broaden the base of elite and near-elite runners to make 1983 happen again? Lessons three, four and five seem like the most actionable lessons to me.

Talent ID — Last time I checked, in the U.S. about 3,000 high school boys per year break 4:30 in the mile, and although not as many, plenty of girls run fast as well. How many of these kids keep running in college in programs similar to those established by coach Larsen? My guess is way fewer than in the good old days. Some of these sub-4:30 milers have never trained seriously and many have never been exposed to a fundamentally sound program. Historically, there are all sorts of 4:30 high school milers who become very good when exposed to a reasonable college program. Capture enough of this talent, nurture it, and some true elites and perhaps a few super elites will emerge. That walk-ons are no longer reflexly welcomed at many college programs is a problem. The talent is there, the pipeline is leaky.

Incentives — In the “good old days,” there were big-deal local and regional races and race series that came with prizes of some sort and a lot of bragging rights among your tribe. If the leaky 4:30 miler pipeline can be fixed, perhaps re-establishing and nurturing some of the local and regional events would make a difference. The shoe and equipment companies also need to think about putting all of their resources in a few post-collegiate runners vs. building a bigger base. Free shoes and a bit of cash to more people might be part of the answer.

Tribes — If the leaky pipeline and incentive issues are fixed, perhaps the tribes like the Jamul Toads, which were clearly an emergent phenomenon, will reemerge, or maybe a better way to put it is re-evolve.

Summary: The excellence and depth of U.S. middle and long distance running from the middle 1960s to the middle 1980s happened because people interested in the sport were thinking but not overthinking what it took to be good. A number of larger cultural vectors were also aligned. Running to the Edge is a case study of how this happened and offers an informal road map about how it could happen again.

Michael Joyner is a researcher at the Mayo Clinic, these views are his own. You can follow him on Twitter @DrMJoyner

LRC note: Joyner was on the recent Freakonomics podcast on exercise, which talks about exercise in a pill and a new type of doping cyclists were using.

More Running to the Edge: Author Matthew Futterman is a guest on this week’s LetsRun.com podcast and discusses his new book.

(Disclosure: If you buy from an Amazon link, LetsRun.com gets a commission)