Six Years After Seeing The First Atomic Bomb Detonate in Hiroshima, Shigeki Tanaka of Japan Won the Boston Marathon

From Hiroshima to Boston: Shigeki Tanaka’s Journey to Become The First Japanese Winner of the Boston Marathon

By Jonathan Gault

April 10, 2017

April 19, 1951 — Patriots’ Day in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts — was, as always, a massive day for sports in Boston. The Boston Braves were hosting a doubleheader against Bobby Thomson‘s New York Giants. The Harlem Globetrotters were visiting the Boston Garden. For the first time in history, the Charles River was hosting an international crew race — Cambridge University had traveled from England to face off against local squads from Harvard University, Boston University and MIT. And at high noon, 153 men gathered 26 miles west of the city in Hopkinton to run the 55th Boston Marathon.

The national champions of the United States, Canada, Greece, Turkey and China all stood on the starting line that day along with future Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis, then a 17-year-old out of nearby Chestnut Hill representing Tracy Athletic Club. But the four men who drew the most intrigue hailed from Japan, a country that, at the time, was still under U.S. occupation. They wore white shorts and white singlets with two thick stripes running from the right shoulder down to the left hip. The Japanese flag, with its red circle representing the rising sun, was plastered front and center on their torso, just above their race numbers. Two of them, Shigeki Tanaka and Shunji Koyanagi, wore rubber-soled shoes with canvas uppers split in two at the toe, which they believed offered superior grip. The American press had never seen anything like it.

Less than six years earlier, a 14-year-old Tanaka had watched from a nearby village as an atomic bomb crippled the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. On April 19, 1951, he won the Boston Marathon.

***

Though the events of World War II were impossible to forget, by 1951 the nation’s attention had moved on to the Korean War, and this was reflected in the Boston Athletic Association’s invitation policy for that year’s marathon. Despite sweeping the top three places in the 1950 edition, Koreans were not welcome in Boston.

“While American soldiers are fighting and dying in Korea, every Korean should be fighting to protect his country instead of training for marathons,” said B.A.A. president Walter A. Brown. “As long as the war continues there, we positively will not accept Korean entries for our race on April 19.”

At the same time, however, race director Will Cloney extended an olive branch by inviting Japan to send a team to the race. Though the 1951 Boston Marathon was not the first international post-war sporting event to feature Japanese athletes (a Japanese team had competed at the Asian Games in New Delhi one month earlier), it was the first major U.S. sporting event to do so.

Since he began running, Tanaka’s dream had been to compete at the Olympic Games. And though Japan had been banned from the 1948 Olympics, Tanaka believed that his country would be invited to the next edition, in Helsinki in 1952. Boston was not the Olympics, but if he could earn selection and run well there, he’d put himself in great position to make the Olympic team.

The Japan Marathon Association staged a trial race to select the four-man team. Tanaka won in a personal best of 2:28:16, coming from behind to upset Koyanagi, the reigning Japanese champion. The team was as follows:

- Shigeki Tanaka, 20, 5’4½”, 118 lbs., from a village about 30 miles outside of Hiroshima. Baby-faced with light brown skin, Tanaka was set to enroll at Nihon University upon his return to Japan. The only runner on the squad not sponsored by a corporate team.

- Shunji Koyanagi, 26, 5’6″, from Yamaguchi. A bespectacled Nihon graduate who worked at a mining company.

- Hiromi Haigo, 22, from Tokushima. A salt company employee who made the team despite a damaged tendon in his left leg.

- Yoshitaka Uchikawa, 19, 5’3″, from Fukuoka. A coal miner.

In addition, the team was accompanied by two managers: Heita Okabe, 59, who had gone to school in the U.S. and played freshman football at the University of Chicago under legendary coach Amos Alonzo Stagg, and Seiichiro Tsuda, 44, a sportswriter who doubled as the team’s coach. Tsuda had finished fifth in the 1932 Olympic marathon in Los Angeles.

The group departed Tokyo by plane on April 2, making stops in Hawaii, San Francisco and New York before arriving in Boston on April 6, just under two weeks before the race. Japan was still reeling from the war and Tanaka felt immense pressure to represent his country well. One of his teachers told Tanaka it was important for him to learn how to eat with a knife and fork; any slight misstep could be seized upon by the American press.

“We had no money,” Tanaka told the Boston Globe‘s Charles Radin in 1996. “Ordinary people donated to help us go. Because of these things, we felt we just could not lose. We didn’t really talk about it, but we understood each other’s feelings well. If we did not win, we could not go home…In each place, we went to a movie theater and people wrapped money in paper and threw it on the stage. I felt pretty strange to receive money like that, like a beggar almost . . . We bought sugar to bring back to Japan — that’s how bad things were.”

In Boston, the Japanese team was put up in an apartment in the South End and spent their days training at Harvard University. After the Koreans’ success in 1950, sportswriters were eager to get to know the Japanese, especially Tanaka. Though his 2:28 personal best would have easily won the last three Boston Marathons (Editor’s note: After a WR of 2:25:39 was set in Boston in 1947, the winning times in 1948-49-50 were all over 2:31), reporters were more taken with his backstory. Growing up on a farm outside of Hiroshima, Tanaka was on his way to school on the morning of August 6, 1945, when he saw a bright flash in the sky followed by a lot of smoke. He felt a tremor in the ground and wondered whether there had been an earthquake.

It took a while for Tanaka to find out what really happened. Later that day, survivors of the first atomic bombing in history, their clothes burned off, made their way into his village. No one in Tanaka’s family had been harmed. Ten days after the bombing, Tanaka and some other boys went to Hiroshima to offer what help they could provide.

“Everything was flat,” Tanaka told the Globe the day after the marathon. “We saw bodies floating in the water and in the rubble still. Water was gushing out of broken pipes everywhere. Some parts of the city had been roped off by the police. [In the big buildings], inside, they were all gone. Some of the walls still stood, but they were cracked and useless. Everything had to be torn down.”

In general, Tanaka received a warm reception in the United States, but “I found it a burden that The Boston Globe called me ‘atomic boy,'” he told Radin in 1996.

Tanaka was among the favorites; several experts in the Globe, Boston Daily Record, Boston Post and Boston Evening American all picked him to win.

“If he could survive the atom bomb, he ought to survive our hard highways and hills,” said Boston Garden VP Tom Kanaly, who picked Tanaka in the Evening American.

One concern about the Japanese runners, however, was that they trained mostly on level ground, making them ill-suited for Boston’s hills. The favorite in the Globe‘s expert poll was a 33-year-old American named John Lafferty, who at 6’0″ and 155 lbs, towered over the Japanese. An aviation mechanic in the navy stationed at Quonset Point in Rhode Island, Lafferty was the top returner, having placed fourth in 1950 (2:39:52), and fit his training around his busy schedule at the naval base. He had to secure a two-day leave pass from the Navy just to run the marathon.

Another local hope was Bob Black, the 1949 and 1950 NCAA cross country champion at Rhode Island State College (now the University of Rhode Island) who at the time of the race was working as a swim instructor at the Providence YMCA. Black, who would turn 29 on race day, had never raced beyond 20 miles, and many pundits were skeptical of his ability to handle the distance: he had run just 50 miles, total, in January, 100 in February and 167 in March. But he entered in good form: with the Japanese contingent watching from the lead vehicle, he had won the 12-mile Hyde Shoe A.A. road race in Cambridge on April 7 in a course-record 1:05:17.

Other challengers included Anasthasios Ragazos, the Athenian bank clerk who had finished sixth in 1947 (2:35:34), American Jesse Van Zant — attempting to become the B.A.A.’s first champion in its signature race — and of course Tanaka’s Japanese countrymen.

“Mr. Koyanagi probably will lead for three-quarters of the race,” Okabe told the Globe‘s Jerry Nason before the race, though he warned that Tanaka and Haigo were both strong second-half runners.

***

Since its inception in 1897, the Boston Marathon has always been held on Patriots’ Day, a state holiday in Massachusetts and Maine. Patriots’ Day is currently observed on the third Monday in April, but until 1969 it was always observed on April 19. As a result, the 1951 Boston Marathon was held on a Thursday.

The Japanese runners always ate 90 minutes before competition, so on race day morning they had planned on eating their pre-race meal in Boston at 10:30 a.m. before heading to the start line in Hopkinton. But at the time, marathon running was not the free-for-all it is today; all runners had to pass a pre-race medical exam in Hopkinton on the morning of the race before they were allowed to start. As a result, the Japanese team ate their meal in nearby Framingham instead, arriving in Hopkinton at 11:20 to give them time to be examined. After passing their exams and changing into their racing gear, Tanaka, Koyanagi, Haigo and Uchikawa headed for the start line. Haigo, like Tanaka, felt pressure to represent his homeland, even though he carried a right leg injury into the race.

“Our people gave money to send me all this way. I just had to run for them,” Haigo later told the Globe, through an interpreter.

With most Boston-area residents having the day off work, the marathon was always a major draw for fans, and conditions were good for running and spectating in 1951, with temperatures in the 50s. But crowds were down significantly — the Boston Daily Record estimated 250,000 spectators, 100,000 fewer than the year before. The reason was not hard to surmise. Eight days earlier, Douglas MacArthur had been relieved of his duties as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Japan and Commander of the United Nations forces in Korea. He was in Washington, D.C., to address Congress, and the speech would be carried live on television as far west as Omaha. In Boston, WBZ-TV came on two hours earlier than normal just for MacArthur’s speech: 11:30 a.m., just half an hour before the marathon was due to start. The Boston Herald reported that 1.5 million people watched MacArthur’s speech in Boston alone, with many of those who did not own a television gathering in stores, restaurants and bars to hear MacArthur tell the country, “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away.”

“For the first time since any of the officials could remember Kenmore Square was almost bare of observers and the police ropes on Beacon Street were sad and lonely,” reported the Post.

Koyanagi didn’t care. He took the race out hard from the gun, stringing out the field, and his split at Woodland Park in Newton at 16.8 miles (1:31:35) was a new course record (that’s 2:22:56 marathon pace). At the time, Tanaka and Uchikawa were the next-closest runners, around two minutes back of Koyanagi. But they still had the Newton hills to come. Before the race, Tsuda had advised Tanaka to be patient early before attacking on the hills. If he did that, Tsuda told Tanaka, he would have the lead by the end of the hills at mile 21. True to form, Tanaka threw in a surge after passing Woodland Park, quickly dropping Uchikawa as he began to reel in Koyanagi.

“Going over that rough climb past the Brae Burn Country Club, Tanaka moved faster than any marathoner has ever done before,” Murray Kramer wrote in the Daily Record.

Tanaka sped up Heartbreak Hill and though Koyanagi still held the lead at Lake Street in Brighton, just past Boston College (1:57:10 at 21.2 miles, on pace for a 2:24:55 marathon — which would have been a world record), Tanaka had trimmed the deficit from 600 yards to 100. Half a mile later, just before the left turn at Cleveland Circle, Tanaka caught and passed Koyanagi. Only one adversary remained: the clock.

As strong as Tanaka had looked on the hills, even he was starting to hurt as he plowed down Beacon Street in Brookline. As he passed Coolidge Corner (23.6 miles in 2:12:23 — 2:27:05 pace), he heard a voice (it is unclear whether this voice spoke English or Japanese):

“Two more miles! You’re six seconds behind the [course] record!”

Tanaka immediately sped up, only to step back into his previous pace after a few steps.

“I figured it was better to win the race than to lose it trying to break the record,” Tanaka told the Post afterward.

|

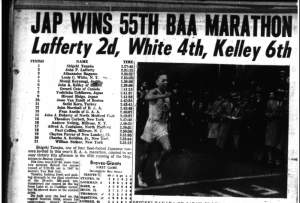

1951 Boston Marathon results 1. Shigeki Tanaka (JPN) 2:27:45 |

Tanaka won comfortably, by over three minutes, but his winning time of 2:27:45 put him well back of the course record of 2:25:39 (later it would come out that, due to road construction, every Boston Marathon from 1951 to 1956 was short). Lafferty once again finished as the top American, moving up smartly for second in 2:31:15, while Koyanagi paid for his suicidal early pace, fading to fifth in 2:38:36. The fears about Bob Black being unable to handle the distance proved correct as the former NCAA champ failed to even break three hours, taking 32nd in 3:01:57.

In recent years, rumors have swirled on the internet (also here) that the crowd was silent as Tanaka crossed the finish line. However, there are no facts to support this. In fact, through an interpreter, Tanaka told LetsRun that “when I cross the finish line, everybody was excited.”

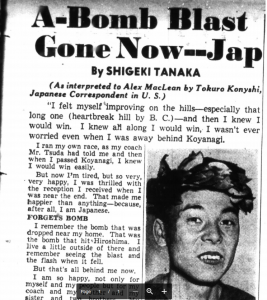

“I was thrilled with the reception I received when I was near the end,” said Tanaka, who broke into a wide grin at the finish, to the Daily Record. “That made me happier than anything–because, after all, I am Japanese.”

After the race, Tanaka was quickly shuffled into a nearby building for a medical checkup. From there, he was taken to the Lenox Hotel to relay news of his win back home to Japan before meeting with the assembled press. Tanaka was particularly excited with the photographers. In his country, it was an honor for an athlete to have his picture taken.

What he wanted more than anything, however, was some food. Back in Japan, hot soup and snacks were made available to runners on the course. That was not the case in Boston, and Tanaka had not eaten anything during the course of the race. He told reporters from the Herald that his (literal) hunger was one of the two things that motivated him to win, along with doing it for the folks at home in Japan. Uchikawa was of a similar mind. Rather than congratulate his countryman, the first thing he did after finishing was ask a Harvard graduate student where he could get some food. He was led to the dressing room, where he promptly downed 10 cupcakes.

Tanaka, Koyanagi and Uchikawa returned to their South End apartment before driving to City Hospital to check on Haigo who, x-rays revealed, had run the race with a hairline fracture above his ankle. Despite Tanaka’s victory, the mood was one of disappointment: the goal had been for the Japanese team to match the Koreans’ 1-2-3 finish of a year earlier, and during the car ride Tanaka and Koyanagi were already plotting how they could improve in 1952 as a famished Uchikawa feasted on oranges and miso soup.

***

The next day, Tanaka awoke at 8 a.m., an hour later than usual, and began sifting through the Boston newspapers and clipping articles about his victory, even though he could not read the headlines. Perhaps that was for the best.

JAP WINS GRIND; LAFFERTY 2D, read the headline in the Daily Record. The text, in several cases, was even worse, making light of an event that had caused the deaths of over 100,000 of Tanaka’s countrymen. The Globe‘s Jerry Nason was the worst offender. Some excerpts from his story:

“Shigeki Tanaka from faraway Hiroshima, Japan, unloading point for history’s first atom bomb, is by no means radioactive. Bu [sic] he was so far ahead of his Marathon opposition yesterday afternoon that it appeared as if they feared to approach him without a Geiger counter…Exploding the swiftest of all flights over the tumbling hills of Newton…Sped the 26 miles, 385 yards between Hopkington [sic] and Exeter st. in atomic time…The brown bomber from Hiroshima.”

For lunch, Tanaka and an interpreter were invited to the office of Joseph L. Malone, Boston’s director of civil defense. He was asked several questions about the bombing, concluding by telling Malone that the resentment of the people of Hiroshima against the USA has “pretty well died out now,” according to the Globe.

Afterward, Tanaka and the rest of team Japan headed to Fenway Park. They were mobbed by autograph seekers as they watched Ted Williams and the Red Sox lose their home opener to the Philadelphia A’s, 6-3.

Initially, the Japanese runners had planned to stay in Massachusetts and run the 12-mile Race of Champions in Springfield three days after the marathon, but unsurprisingly, Okabe scrapped those plans.

“All too tired,” he told the Globe. Instead, they began the long journey home on April 21, making stops in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Hawaii before returning to Tokyo. The victorious Tanaka was feted all the way home. He toured American museums, where he particularly enjoyed the Japanese art on display, and met Joe DiMaggio and Olympic swimmer turned actor Johnny Weissmuller. Back in Japan, the city of Hiroshima threw Tanaka a victory parade.

A selection of Boston newspaper headlines after Tanaka’s victory. Note the liberal use of the derogatory term, “Jap,” despite the fact that World War II had ended over five years earlier.

- Boston Evening American

- Boston Post

- Boston Daily Record

- Boston Daily Record

- Boston Daily Record

***

Tanaka did not return to Boston in 1952; none of the Japanese did, with it being an Olympic year. However, Tanaka did not run at the Olympics in Helsinki either, a leg injury cost him a spot on the team. Of the four who traveled to Boston, only Uchikawa ran at the Olympics, but he did not finish. But their trip to Boston in 1951 had set the stage for a string of Japanese successes in Boston over the next two decades.

“Both on the Japan side and then on the Boston side/U.S. side, that win certainly put the Japanese on the map, like ‘Oh yeah, let’s invest in these guys,'” said Brendan Reilly, an agent with a deep knowledge of Japanese running given he spent six years living in Japan and has worked with Japanese athletes for over 20 years, including Olympic marathon champions Naoko Takahashi and Mizuki Noguchi.

Tanaka actually never ran Boston again, as custom at the time dictated that Japanese winners did not return in order to give other Japanese runners a shot at glory. Instead, in 1953, when Japan sent another squad to Boston, Tanaka saw the runners off at the Tokyo airport. Keizo Yamada claimed the victory that year, with Hideo Hamamura earning another win for Japan two years later.

Those victories, coupled with Tanaka’s win, had an impact on the next generation of Japanese runners.

“I think one, because it was Boston, and two, because it was one of the first big international events that was inviting Japanese, it was huge,” said Reilly. “It changed the mindset for a lot of younger runners in the way Kenyans going through the ’90s, the ’80s are just like ‘Oh yeah, I’ve gotta go to Boston. If I’m going to be a good athlete, Boston is where I’m going to go run.’ And I think during the ’50s and the ’60s, short of the Olympics — because there was no World Championship — your next-best goal would be ‘I want to get myself to Boston.'”

“Because Tanaka and Yamada won there, Boston’s reputation was really high in my generation; it always caused a warm feeling,” 1969 Boston champ Yoshiaki Unetani told the Globe in 1996.

In all, between 1951 and 1969, Japan sent athletes to Boston on 10 occasions. Six times, they came away with the laurel wreath, including 1-2-3 sweeps in 1965 and 1966 (Editor’s note: they won in 1951, ’53, ’55, ’65, ’66, and ’69, plus 1981 and ’87).

Tanaka, meanwhile, settled into a career at a Tokyo-area department store. He returned to Boston for the 100th edition of the race in 1996, as well as the 50th anniversary of his win in 2001. In between, his winner’s medal was stolen from a safe underneath his bed in May 1998. The B.A.A. delivered a replacement medal to Japan, which Tanaka was awarded in July, though the original medal was recovered shortly thereafter. Now 86, Tanaka lives in Utsunomiya, 80 miles north of Tokyo, his home for the past 57 years.

Special thanks to Gloria Ratti of the B.A.A. and Masaru Otake for putting us in touch with Tanaka.