Book Review: The Emil Zátopek Biography “Today We Die A Little” by Richard Askwith Is A Fine Work

“Today We Die A Little is a fine work… It is rare to find a biography better-researched than this one. If Askwith says he doesn’t have the definitive answer on something, you can rest assured that no one else alive does, either.”

By Jonathan Gault

May 25, 2016

Czech legend Emil Zátopek — the man whom Runner’s World, in 2013, named as the greatest runner of all time — is a very popular man these days.

Yesterday, two English biographies of Zátopek were published. In June or July, Zátopek’s widow, Dana, will publish her own biography (in Czech) but that will only be the third Czech language book on him in recent months as a comic book and regular book have already been published.

Pat Butcher’s book on Zatopek is coming out later this summer

Pat Butcher’s book on Zatopek is coming out later this summer

And in a few months, respected British journalist Pat Butcher, whose work we’ve often linked to on his www.globerunner.org website as he’s been covering track and field for 35 years, is also slated to release a biography on Zátopek, whom he interviewed before he died in 2000. His book will be called, QUICKSILVER – The Mercurial Emil Zátopek.

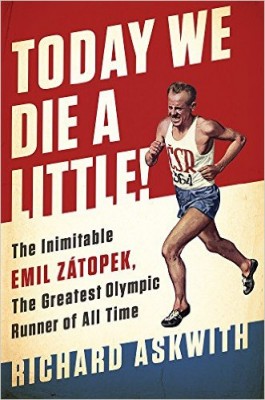

So far, I’ve only read one of these books, Richard Askwith‘s Today We Die A Little!: The Inimitable Emil Zátopek, The Greatest Olympic Runner Of All Time (the other released yesterday was Rick Broadbent‘s Endurance: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Emil Zátopek). And while I can’t call it the definitive Zátopek biography, which would obviously necessitate reading the other books, it is a fine work.

Askwith, who is the author of running books Running Free and Feet in the Clouds, had two main objectives in writing Today We Die A Little!: 1) separate fact from fiction and 2) show the human side of a legend. He summarizes them well in the prologue:

“Every running enthusiast over a certain age knows something about Zátopek — or thinks they do. But much of it is no more than hearsay: legends and half-truths endlessly recycled and re-embroidered. Many of the most famous tales are simply false. Even those of us who idolize him — who see him, as I do, as a kind of patron saint of running — are liable to find, on closer inspection, that we know far less about him than we think…It is the human side of Zátopek’s story that is still capable of brightening and energizing lives, six decades after his prime and a decade and a half after his death. That is the story that matters.”

There is a reason that, as Askwith writes, “we know far less about him than we think.” Zátopek came of age in a communist Czechoslovakia that punished free speech and prioritized homogeneity. Zátopek was no one until his athletic talent became too great to ignore; from then on, the Czechoslovak government utilized him as a propaganda machine, a living embodiment of the greatness the country could achieve. On foreign trips, Zátopek was never without a handler taking notes on what he said or did.

There is a reason that, as Askwith writes, “we know far less about him than we think.” Zátopek came of age in a communist Czechoslovakia that punished free speech and prioritized homogeneity. Zátopek was no one until his athletic talent became too great to ignore; from then on, the Czechoslovak government utilized him as a propaganda machine, a living embodiment of the greatness the country could achieve. On foreign trips, Zátopek was never without a handler taking notes on what he said or did.

So Askwith is not only trying to piece together the details of events that took place over half a century ago, but he’s trying to determine the character of a man who was barely allowed to show it publicly, aside from the ever-present grimace stapled to his face on the track and perfunctory smiles when the Czechoslovak government trotted him out for events. It doesn’t help that Zátopek was never one to let the truth get in the way of a good story, allowing some of the more unbelievable tales about his life to spread.

It is a monumental challenge, and Askwith dives in with both feet, traveling the modern-day Czech Republic for answers and drawing on lengthy interviews with Dana, Zátopek’s widow (and an Olympic gold medallist herself in the javelin). The sporting accomplishments were the easier part to document, and Askwith does a superb job running through Zátopek’s career chronologically, from small races in tiny Czechoslovak towns to Olympic finals in London, Helsinki and Melbourne. Askwith is smart enough to know which races require extensive backgrounds and detailed summaries and which ones simply require the results to be stated, which is important in a book as long as this one (377 pages). We also get snippets of Zátopek’s insane training regimens, including a 10-day stretch prior to the 1948 Olympics where he ran 60 x 400, every day.

But pinning down Zátopek the man is a nearly impossible task, and Askwith is honest with his shortcomings in this department. When he doesn’t know something, he admits it and explains why. And though the reader will find Askwith does this more often than most biography authors, it says more about Askwith’s assiduousness than any failing on his part. With 55 pages of detailed notes at the back of the book providing backup for almost every factual statement, it is rare to find a biography better-researched than this one. If Askwith says he doesn’t have the definitive answer on something, you can rest assured that no one else alive does, either.

With those restraints, Askwith does his best to describe Zátopek’s warmth and generosity, though at times the work slips into hagiography — Askwith even admits to hero-worship in the epilogue. It does make the reader question the author’s motives — after all, if the purpose of writing this book was to show the human side of the “patron-saint of running,” it might be in Askwith’s best interest to bury the less saintly qualities of Zátopek’s life. But Askwith investigates the negative claims about Zátopek with even more vigor than he does the glorious legends. He admits that Zátopek briefly experimented with amphetamines in the 1940s, details a 1950 letter in support of the communist dictatorship that bore Zátopek’s signature and dedicates an entire chapter into investigating a claim that Zátopek was an informer for the StB, the Czechoslovak secret police (this appears unlikely).

Askwith spends a lot of time digging into the effect of politics on Zátopek’s life, and the result is some of the book’s richest work. Zátopek did take a stand for his beliefs during the revolutionary Prague Spring of 1968, speaking out against the Soviets, communism and the Czechoslovak army. But once the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia to restore order, Zátopek was essentially blacklisted from most jobs and forced into a migrant existence as a well driller. The subsequent five-year exile from society broke Zátopek and stripped him of the joyful demeanor that won him so many friends during his athletic career; eventually, Zátopek recanted his statements and returned to a quiet life with Dana in Prague.

When we think about issues like this, it is easy to do so in absolutes. Zátopek wasn’t willing to die for his beliefs, which some might call weakness, but others might call a sign of pragmatic intelligence. What Askwith argues for, compellingly, is a shade of gray. What Zátopek did wasn’t “right” but that doesn’t make it “wrong” either. To truly understand why a person made the decisions they made, you’ve got to get in their shoes and see what they saw. Askwith does exactly that with Zátopek.

You can purchase the book and support LetsRun.com in the process at the link below (or you can wait until all three English biographies are out and we’ve had time to review the other two).

Previous book reviews by LetsRun.com can be found here.