A Day with Olympic Marathon Champion Eliud Kipchoge, Part II: A Look at Kipchoge’s Spartan Training Camp & Why He Is Part of Nike’s Breaking2 Attempt

By Jonathan Gault

May 3, 2017

In March, LetsRun.com had the opportunity to spend a day with Olympic marathon champion Eliud Kipchoge in Kenya, seven weeks before he attempts to be the first human to run under two hours in the marathon. What follows is a two-part look at the 32-year-old Kipchoge. Part I, which you can read here, features an early-morning track workout in Eldoret. In Part II below, LetsRun.com traveled to Kipchoge’s training base in Kaptagat, where we toured the Global Sports Communication camp and discussed Kipchoge’s career and why he’s part of Nike’s sub-2:00 project, Breaking2.

A photo gallery of Kipchoge’s workout is here and of his training camp here.

KAPTAGAT, Kenya — Ever since Nike announced Breaking2, its audacious plan to produce history’s first-ever sub-2:00 marathon, back in December. The questions have flown around in running circles. Where will it be? When will it be? And how the heck will they actually do it?

Details have trickled out slowly over the ensuing months, but to hear Eliud Kipchoge tell it, even he doesn’t know everything about the “race.” And he’s running in it.

“I don’t know the date,” Kipchoge says on a sunny morning in late March, sitting in a plastic chair on the lawn of his training camp in Kaptagat. “I am training and am focusing for any date. I’ll be comfortable with any date. My job is to train and make sure that I am fit. [Nike’s] job is to look for the weather, make arrangements and everything.”

Nike has also announced that the time will not be eligible for the official IAAF world record, but Kipchoge says he is not certain why that is the case.

“Maybe about pacemaking? All in all, I don’t know about not making world record. My happiness is to run under two hours. So even if they say it’s a world best, I am the first human being to run under two hours.”

Kipchoge and his training mates relax after a morning workout. Photo by Weldon Johnson. camp photo gallery here

Kipchoge and his training mates relax after a morning workout. Photo by Weldon Johnson. camp photo gallery here

Since that interview, Nike has announced that the race will take place this weekend, sometime between Saturday, May 6 and Monday, May 8 (depending on which day has the best weather conditions) at Autodromo Nazionale Monza in Monza, Italy. Nike has yet to explain precisely what about the attempt will not make it eligible for the world record, but Kipchoge’s hunch is most likely correct. Nike will sub in pacers midway through the race, a no-no in the eyes of the IAAF, in order to break the wind for Kipchoge, Ethiopia’s Lelisa Desisa and Eritrea’s Zersenay Tadese, the three men tasked with pulling off the impossible and covering 26.2 miles almost three minutes faster than anyone else to this point in human history. The three racers also will be handed their refueling bottles instead of having the slow to pick them up at aid stations, as they would in a normal race.

But for all the riches Nike has poured into the project, it will be a man, not a company, that breaks the barrier. And if it is to happen this weekend, Kipchoge, the Olympic marathon champion, is by far the most likely to do it. At Nike’s test run March, Desisa could not even manage sub-2:00 pace for 13.1 miles, running 62:55. Tadese, the world record-holder in the half marathon, has never broken 2:10 in four attempts at the full 26.2-mile distance.

The smart money is that no one cracks the two-hour barrier this weekend.

“I would say breaking it this weekend has a very, very minimal chance,” says Steve Magness, an exercise physiologist and coach for the University of Houston and several elite runners. “Just based on what they’ve optimized and what they’re banking on to get the extra almost three minutes, I don’t think they’ll get there.”

(For more on why the sub-2 isn’t likely, come back tomorrow and read our preview of the race which explains why it’s not likely to happen: LRC Breaking2 Preview: Sorry, Eliud — The Experts Explain Why a Sub-2:00 Marathon This Weekend Is Impossible).

So if that’s the case, why would Kipchoge skip out on a major marathon in the prime of his career to take part in some science experiment? I tried to figure that out.

***

Kipchoge’s Breaking2 gear drying in the sun. Photo courtesy Jean-Pierre Durand for the IAAF. camp photo gallery here

Kipchoge’s Breaking2 gear drying in the sun. Photo courtesy Jean-Pierre Durand for the IAAF. camp photo gallery here

A couple hours after his morning workout, Kipchoge is leaning forward out of his chair, angling for a better view as music plays from the small portable radio behind him. He and half a dozen other athletes represented by his agency, Global Sports Communications, are relaxing at their training camp, doing their best to stay out of the sun before they have to run again this afternoon. One of his training partners has pulled up a video on his smartphone, and Kipchoge watches intently, laughs, and eventually falls back into his seat. While they sit in the shade, to their left, their clothes from the morning workout are strewn across the grass, drying in the sun. Somewhere in their reside Kipchoge’s specially designed Nike Zoom Vaporfly Elites, the same model he will wear for the sub-2:00 attempt.

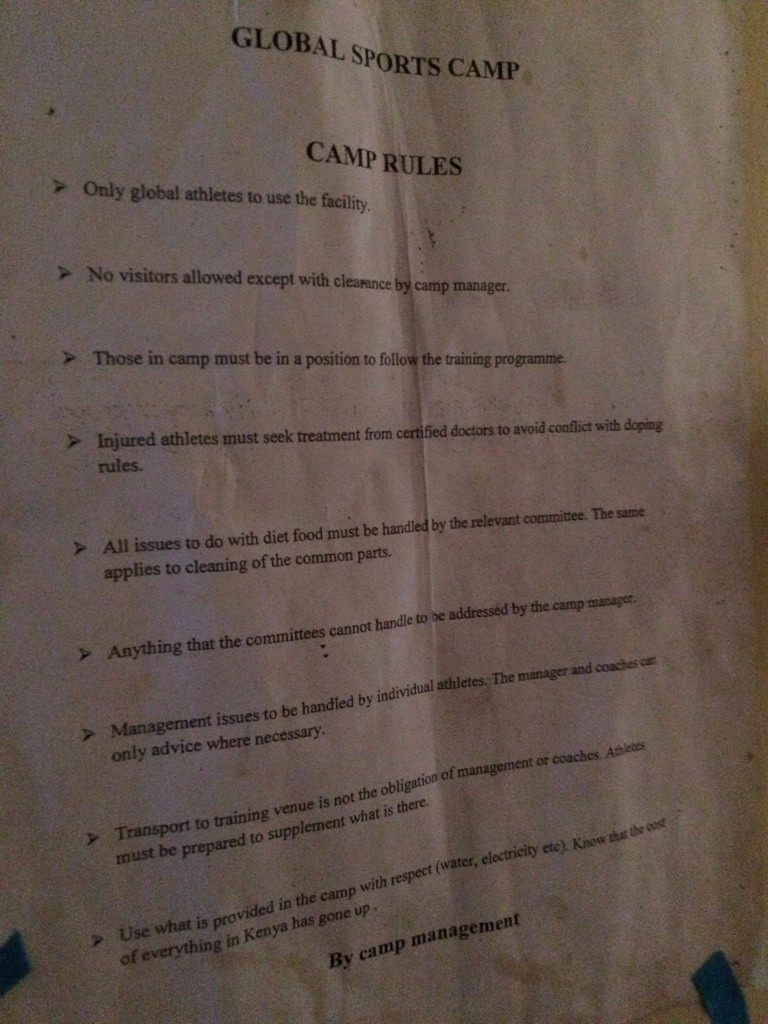

He has trained at Global’s camp, located in Kaptagat, a village in western Kenya 30 minutes southeast of Eldoret, for the past 13 years, ever since he burst onto the scene as an 18-year-old by defeating legends Hicham El Guerrouj and Kenenisa Bekele to win gold in the 5,000 meters at the 2003 World Championships in Paris. Set back from the main road, the camp sits on the edge of Kaptagat Forest and consists of two single-floor brick buildings with metal roofs. Out front, there’s a lawn that serves as communal area/parking lot, the grass worn out by the 25 athletes who spend most of the year living here. The interior of the main building resembles a rudimentary college dorm, housing several small eight-by-ten-foot rooms. A set of camp rules is posted on the wall, alongside a hand-written chore schedule — Kipchoge’s name is spelled incorrectly (“Eluid”), as is the one below it: “Geofrey Kipsang,” referring to two-time World Cross Country champion Geoffrey Kipsang Kamworor. Behind the main building, there’s a garden and a well and off to the left, behind a wooden fence and the half-dozen cars parked on the property, sits a makeshift dirt track with a black and white cow casually grazing in the infield. The “weight room” consists of a single metal bar with two cement blocks on each end.

It’s a simple setup. If Quenton Cassidy, the fictional protagonist of the cult classic Once a Runner, had to train in Kenya, one imagines he’d do it at a place like this. And Kipchoge wouldn’t change it for the world. He sees his wife and three children (Lynne, 10; Griffin 6; and Gordon, 3) on the weekends, but living in the camp forces him to concentrate. There is a small TV in one of the buildings, but there’s not much else to do in the camp. Running is the most important activity of the day, basically by default.

“I have never even in my front of my mind and back of my mind, I have never [thought about leaving the training camp],” Kipchoge says.

Kipchoge with the Global camp’s cook, Mary. Photo courtesy Jean-Pierre Durand for the IAAF. camp photo gallery here

Kipchoge with the Global camp’s cook, Mary. Photo courtesy Jean-Pierre Durand for the IAAF. camp photo gallery here

Patrick Sang, Kipchoge’s longtime coach, is the man responsible for bringing Kipchoge to Kaptagat. Both men hail from the same hometown, Kapsisiywa, in nearby Nandi County. When Kipchoge started to show promise as a teenager, Sang began providing Kipchoge with clothes, shoes and workouts to aid in his development. But their bond goes back even further.

“When I was young, you normally see Patrick Sang in the tea field all the time,” Kipchoge says. “Sometimes when you are walking to school and he’s around training on the road. My mind was just, one day I want to see if I can run like him in future.”

Once Kipchoge began making Kenyan national teams, Sang brought him to the Global camp. Kipchoge has since ascended to the pinnacle of the sport, but in Kaptagat, he remains an equal. His victories have earned the admiration of his peers, but unlike other marathon training groups in Kenya, which are often centered around the best athletes, such as Wilson Kipsang, who dictate the schedule and workouts, Sang remains the undisputed leader. Kipchoge instead functions as the perfect example of a Sang athlete: hard-working, dedicated and obedient, with an unshakable devotion to his coach. He is the athlete others strive to emulate.

“When somebody succeeds, some people think this is the right way to move, to [follow Kipchoge’s example],” says Richard Metto, who has served as Sang’s assistant since 2010. “Because you do not follow a failure. You always follow someone who is in the process of going ahead.”

Now, Kipchoge is the one providing the inspiration. When 24-year-old Geoffrey Kamworor, Kenya’s next great distance star, won the World Cross Country Championships in March, he did so in spikes with a single word stitched along the heel: ELIUD.

***

Steeplechaser Brimin Kiprop Kipruto chats with Kipchoge. Photo courtesy Jean-Pierre Durand for the IAAF. camp photo gallery here

Steeplechaser Brimin Kiprop Kipruto chats with Kipchoge. Photo courtesy Jean-Pierre Durand for the IAAF. camp photo gallery here

The 32-year-old Kipchoge took to the marathon so easily and progressed so rapidly that it is a wonder it took him so long to make his debut, a 2:05:30 victory at age 28 at the 2013 Hamburg Marathon. But Kipchoge is a man who craves order and follows through on his plans, and he mapped out his career path long ago, even as his remarkable endurance began to shine through in his weekly long runs: he vowed to race on the track for 10 years — “10 good years,” Kipchoge adds — before turning to the roads.

During those 10 years, Kipchoge was more than good. He won in his very first appearance at a global senior championship, the 2003 Worlds. The fact that Kipchoge says he views that race, in which he reached the pinnacle of the sport, as “the beginning of my life in athletics” shows just how rare his talent is. He went on to earn two Olympic medals in the 5,000 (bronze in 2004, silver in 2008) and a silver at the 2007 Worlds, earning personal bests of 3:50.40 for the mile, 7:27.66 for 3,000 meters, 12:46.53 for 5,000 meters (#4 all-time) and 26:49.02 for 10,000 meters. He was consistently among the world’s best during his entire career on the track: from 2003 through 2012, his 5,000 season best was slower than 13:00 only once — in 2008, the same year he took Olympic silver.

But after failing to make the Kenyan Olympic team in 2012 — he finished 7th in the Kenyan Olympic Trials in both the 5,000 and the 10,000 — Kipchoge transitioned to the roads and didn’t look back. He ran 59:25 in his debut half marathon that fall and hasn’t raced on a track since. He had no interest in pursuing the 10,000 (an event he never ran at Worlds or the Olympics) and felt that his biggest remaining goal — an Olympic gold medal — could still be accomplished in the marathon.

“There is not difference between a 10k and 5k,” Kipchoge says. “Their trainings are the same. So I didn’t see any meaning in just concentrating in 10k before moving to the road.”

The only TV at the Global camp. Photo by Weldon Johnson. camp photo gallery here

The only TV at the Global camp. Photo by Weldon Johnson. camp photo gallery here

Since that debut win in Hamburg in April 2013, Kipchoge has strung together the greatest four-year stretch in the history of marathoning. He was second that fall in Berlin (where it took a world record from Kipsang to beat him) and has not lost a marathon since, collecting wins in Rotterdam, Chicago, London (twice), Berlin and the Olympics. His 2:03:05 in London last year — which lowered the course record of the world’s most competitive marathon by over a minute — ranks as the fourth-fastest marathon ever run. Over his first seven career marathons, his average time was 2:04:21. Only 11 men have run that fast even once. With an unprecedented five consecutive victories in Abbott World Marathon Majors events and an Olympic gold medal, Kipchoge has proven himself as the world’s greatest marathoner several times over. After winning in Rio, a world record was the only thing left on Kipchoge’s bucket list.

Kipchoge has grown to love the 26.2-mile event. When I ask him why, he responds with three words: “marathon is life.”

“Marathon is life because it’s a big journey and you are running for a long time,” Kipchoge explains. “You feel the pain, you feel all sorts, think a lot of things.”

But none of this explains why Kipchoge would pass up the traditional spring marathon season to take a crack at breaking 2:00. He was only eight seconds off the world record in London last year. He could run much faster than 2:02:57 in Italy, but if he does, it won’t count as an official world record.

Maybe it’s financial. Nike, after all, has poured millions into Breaking2 and the ensuing hype — check out our super shoes! — has drawn the attention of even casual fans. Kipchoge will almost certainly be well-compensated for the attempt by his sponsor for not returning to London, where he could collect a massive appearance fee and prize money from race organizers. But this is a guy who shares an 8-by-10-foot bedroom despite pulling in hundreds of thousands of dollars annually.

Global’s camp rules (camp photo gallery here)

Global’s camp rules (camp photo gallery here)

“I’m not for money at all,” Kipchoge says. “I have never think of going for good money or big money. I don’t want money to destroy my concentration. I know if I run very well, I will get something to help my family. But I am not really on saying let us sit on the table and discuss the money before.”

Kipchoge’s role in this project dates to September 2016, when Nike executives first told him about Breaking2. He said in March he believes “100 percent” that he will break 2:00 this weekend, but it’s hard to tell whether that belief is genuine or whether he’s simply parroting the company line. When I ask Kipchoge when he first believed he could break 2:00, he responds, “Last September.” But later, he tells me that ever since he took up the marathon, “in my mind, it was there that one day I would run 1:59:59.”

Outside of Nike, few believe that the sub-2:00 marathon can be achieved in 2017. Kipchoge’s training has changed very little for this attempt. He’s been doing a little more speed work, and it’s reasonable to think that he may have improved upon his fitness from 2016. But that would only put him in the mid-2:02:30s at best at a normal marathon. Nike’s bet is that putting the world’s greatest marathoner in an environment where all of the variables are optimized is worth about three minutes off the current world record. But even if Nike can control all of those variables, three minutes is a lot to take off. It took 15 years to go from history’s first sub-2:06 marathon to the first sub-2:03.

“I think 2:57 is too much to take off in one go, and I don’t think that the combination of drafting, shoes and hydration will sum to the 2:57 that is required,” says sports scientist Ross Tucker, Professor of Exercise Physiology with the School of Medicine of the University of the Free State.

Kipchoge shrugs off those concerns.

“Don’t mind about the gap,” Kipchoge says. “I will run under 2:00. The gap, that’s about thinking, that’s psychological.”

For better or worse, Kipchoge will be in Italy this weekend, trying to break two hours. Is it good for the sport? That depends on where you stand. But even Tucker, who has reservations about the event, saying it feels “overtly marketed and gimmicky” admits that the scientist in him is interested in what amounts to a real-life experiment.

“It’s interesting to put elite runners, especially Kipchoge at his peak, in this situation of fully supported science and race conditions, and see what it does,” Tucker says. “Like a hypothetical scenario made real. So that’s good.”

Whether you believe Breaking2 is an overhyped marketing stunt or a legitimate assault on a legendary barrier, every runner can feel a degree of kinship with Kipchoge. Running is about testing one’s limits. So far in his marathon career, Eliud Kipchoge has not found his. This weekend, he may finally reach it.

More: Did you miss Part I? LRC A Day With Olympic Marathon Champion Eliud Kipchoge, Part I: A Tuesday Morning Track Workout

Video: Workout Of Champions: Watch Kipchoge’s 5 X 2k, 1k Track Workout In Kenya

Talk about the sub-2 exhibition on our fan forum /messageboard: MB: Nike Sub-2 Prediction Thread.

Note: LetsRun.com spoke to Kipruto in Kenya as part of the IAAF’s Day in the Life program. While the IAAF worked with a travel agency to arrange the author’s travel within Kenya, it had no say in the editorial content of this article and LetsRun.com covered the costs of the author’s travel and lodging (including the travel arranged by the IAAF) while in Kenya.