JK Babbles About The 2011 Boston Marathon

The One Man On The Planet Who Acknowledged In Print The Possibility Of A 2:03 In Boston Tosses His Own Two Cents Into The "Where Does Boston's 2:03:02 'World Best' Really Stand?" Piggy Bank

By John Kellogg

April 21, 2011 - Disclaimer: I'm stating in advance that most

of the following (tailwind benefit excepted) are just my personal ideas based on an

uncharacteristically (for me) hasty look at a relatively small number of

course-to-course comparison stats, an inordinately extensive personal

history with running with tailwinds in places like Waco, Texas (where

there are miles-long stretches of straight road and where high winds

occur often enough for anyone to gauge very accurately what kind of

advantage big tailwinds give), and an awful lot of assuming, gut

intuition, and guessing about what the runners might have been feeling

in the early pack in Boston. Some of it is probably off the mark, so I

will make no attempt to defend it if anyone calls it crazy talk,

but indisputable science which gives a precise conversion for Boston's

2:03:02 to a windless day or on a different course probably isn't coming

anytime soon, either, so I think my guess is as good as most.

In

the end, we are all guessing about where the final result from the men's race at the 2011 Boston Marathon ranks

among the all-time great marathon performances. But this you can take to

the bank: The race was wind-assisted at ground level and

significantly faster because of it. As the saying goes: Common sense ... so rare it's a superpower.

Don't think a 20 mph tailwind makes a substantial difference? On a day which is that windy, go find a straight-shot course, run 10 miles out-and-back at a strong clip (with and against the wind) or maybe try 6 x 1 mile hard out-and-back with 3-minute rest periods. YMMV slightly depending on your weight and the surface area your chest and back expose to the wind, but you'll probably find that much consistent wind assistance is worth between 10 and 12 seconds per mile, meaning you'll run 20 to 25 seconds per mile slower when you turn around and run into that wind.

If the forecasted wind wasn't absolutely guaranteed to make a huge difference at Boston, I never would have mentioned the likelihood of a world-best time. I didn't throw out the possibility of a 2:03 before the race because I had no doubt the top few runners were so much better than those in any other marathon ever contested; nor did I mention it because I knew this big secret that Boston's course, long viewed as one of toughest majors in the world, is really nothing but a piece-of-cake, freewheeling downhill and this just happened to be the year several runners were going to prove it. No, I took one look at the weather forecast. It's the wind, stupid.

How Difficult Is The Boston Course?

So how hard is Boston's course? Well, despite the net elevation loss

of 450 feet, the terrain includes so many progressively-taxing,

rhythm-breaking ups and grueling, quad-blasting downs in the second half

that the virtually constant downhill in the first several miles -

unrecognizable as "pounding" at the time - is actually considered by

many runners to be a wolf in sheep's clothing, exacerbating the distress

that comes later. Plenty of discomfort - along with probable glycogen

depletion and possible cramping and hobbling - awaits the runners who

are unprepared (or unsuited) for the terrain or who let the seemingly

easy going in the early miles fool them into thinking it couldn't hurt

to bank some extra time. Any of the dream-thwarting problems a normal

marathon can spring on a runner in the latter stages are sharply

magnified at Boston. The unique layout seeks out and tests every aspect

of course-specific preparation, execution and determination, and its

exacting nature unquestionably outweighs the large elevation drop.

Boston presents a demanding course for those who get it right, a

nightmare for those who get it wrong.

Despite all of its challenges and "sly old dog" surprises, the course

hasn't traditionally been considered brutal, unfair or even the kind of

course that was low on the list if a personal best was the goal. In the

heyday of US marathoning (the 1970s through the early 1980s), runners

didn't shy away from Boston, fearing it as "too hard" of a course on

which to run a decent time. Reasonably demanding physically and

challenging to execute well, like a historic marathon was expected

to be - yes. Too slow to be a good option - no. Why has this perception

changed? One reason is because in those glory years, there was a

tremendously larger number of Americans who regularly ran marathons at a

more competitive level, and almost all of them pointed toward Boston as

The Race, from the elites dreaming of victory or a sub-2:10 to the guys

who barely qualified for the race, and everyone in between. Americans

rarely ran in such large numbers on the courses that are now known to be

faster, so quite a few of the top marks (and many personal bests among

the masses) each year came from Boston, except in years with miserable

weather, like 1976 (95 big degrees for that death march). But in the

intervening years, as more runners have sought out the races that

guarantee the fastest times with the least discomfort, becoming spoiled

by the relatively easy Chicagos and Rotterdams of the marathon world,

Boston has acquired the stigma of being a bad course for a good time.

Sure, it's noticeably tougher than any of the notoriously easy courses,

as it can really bang up even a durable runner, and a marathoner who

runs Chicago every year isn't likely to set a PR at Boston, but it's a

fair course that isn't horribly slow, as long as you've trained properly

for it.

My first estimate - admittedly no more than a semi-scientific one based

on paltry data - is that under ideal, windless weather conditions for

all courses, Boston is about 75 seconds slower than London, which is in

turn about 30-40 seconds slower than Berlin (site of the official world

record). Given the disparity in the quality of fields between some of

these races, the presence of paid pacesetters in races like London and

Berlin (which is bound to result in additionally faster top marks,

discounting relative course difficulties, but could also possibly be responsible for more elites blowing up - who knows?), and taking into account variable weather from year to year, it would take an extremely

detailed analysis (which would probably be restricted to small-sample

statistics) to come up with course comparison figures having anywhere

near universally-accepted accuracy.

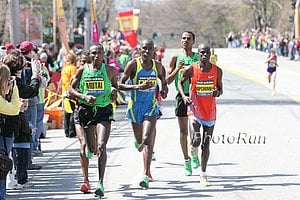

How Much Difference Did The Wind Make?

If all that speculating is as plausible as I think it is, what does it

all mean? It means without the favorable wind, Geoffrey Mutai would have

likely run in the very high 2:05s or low 2:06s in Boston - a similar

performance to Cheruiyot's in 2010 (probably better, since 2010's race

featured a crosswind with a minor assisting component from the West). By

my course comparison estimate (- 75 seconds), this performance would be

somewhere in the middle to high 2:04s on London's course. So I'm saying

add 1:45 or thereabouts to the 2011 Boston times (for the top elites)

to get equivalent 2011 London times (that gives Ryan Hall a 2:06-something,

close to a PR effort). Yep, I can hear the railbirds now: "That's just great ... you're calling

the winning Boston and London performances virtually equal and if you

put them at Berlin, they'd be very close to Haile Gebrselassie's 2:03:59

world record. Way to be evasive and wishy-washy, Kell-Dog." But is it

really a cop-out? I think it reflects the state of elite marathoning in

the world today that the winners of two separate major races can run

2:04 on London's course and the equivalent of that on a wind-aided day

across the big pond on Boston's trickier, quad-busting course. The best

in the world these days can run 2:04s on loop courses if they have to

and perhaps dip under the official world record on the easiest loop

courses. Ryan Hall can and has run 2:06 in London. It adds up.

Then again, maybe I'm subconsciously fudging my course comparisons and

other guesswork so the final numbers will conveniently jive with what I

think the winners of these races are capable of running on a

record-eligible course - 2:04. Maybe I don't want to admit the

possibilities that this year's winning Boston time was actually superior

to the WR or that it might have been worth "only" a 2:05-2:06 at

London. But to reiterate, I'm just guessing and babbling like everybody

else, and it's all but certain that even the nerdiest analysis of all

the variables would still involve enough unknowns and require enough

assumptions that ballpark figures and more babbling are unavoidably as

good as we're going to get for now.

JK Confirms He's A Genius, But Didn't Predict 2:03

Alas, I must admit I didn't have the cojones to actually predict a

2:03 at Boston. If pressed for a predicted time, I would have weaseled

out and gone with a mid-2:04 (still a huge CR), mostly because of the

uncertainty of anyone volunteering to get the early pace going (but it

turned out someone did). I just said I wouldn't be shocked at a 2:03,

and I'm not one bit now that it's happened. Think about it - there was a

2:05-high last year with a marginally favorable crosswind. With a

projected 20 mph direct tailwind, that could easily be more than 2

minutes faster, so if the runners got after it and put up a similar

2:05-type of effort, of course they'd run 2:03. It didn't take a genius to say that. A genius did say it, but it didn't take

a genius. I actually thought they could run sub-2:03, but it's hard to

believe that strongly enough to mention it as a possibility. When you

say 2:02 or anything faster out loud, it just seems a little too far out

of the box - tough to wrap your mind around - even if you know

there'll be a big wind behind the runners and know how much of a

difference it can make. But they came awfully close to the 2:02s.

Obviously, it wasn't so wild a notion after all.

Mutai Over Mutai

Who would have won if all the main players had run in London? I think we

all know Mutai would have beaten Mutai. Would one of the runners who didn't

emerge victorious in either of these races have had his day? How fast

would the winner have run? How about in Berlin or Rotterdam? World

record? Those questions involve even more guessing, since late-race

tactics (and how the courses suit the runners) would come into play. But

we do know that in two back-to-back days, we saw two great races and

two great winners, two course records and the fastest marathon ever run

on any course under any conditions. And - oh, yes - it's not outrageous

to think the winner in London and/or the top two in Boston could have

bettered the WR had they put up their efforts in ideal weather in

Berlin, although I think an equivalent race at that venue would have

resulted in a near miss of about 2:04:10-2:04:20. That's the level at

which the superstars of marathoning appear to be at the moment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Runner's World &

Running Times

Combined Only $22

a Year

Save $87

Running & Track and Field Posters

Great Offer: Nike Lunar Glide Sale Multiple colors of this shoe available.

*Nike Air Max Moto 7 Get 2 Pairs for a Crazy $112